It was 1989. I had recently fallen in love with comics and was just starting to write them. Most of what inspired me was in color, which was great, but I knew I would be working in black and white. I was enjoying the rash of indie b&w comics, but none of the ones I was reading had the depth of story and the kind of immersive artwork I aspired to. Then I found The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, by Bryan Talbot. It showcased the real potential of the b&w independent comic. It was a science fiction, alternate history tour de force. It was smart. It was funny. It was visually stunning. Every time I went back to it, I discovered something new. It was also produced out of the UK. Of all of the people doing comics I loved, I assumed that Bryan Talbot would be one of the last I might meet. So when I discovered that he was at a booth across from mine at Pro-Con at the San Diego Comic-Con, I was elated and trepidatious. Was this going to be an encounter with someone whose work I admired but who turned out to be a jerk? It was in fact the opposite, a case where the person is as amazing as his work.

Fast-forward a few years and a couple of publishers later, and Bryan ended up doing the cover art for my miniseries, Raggedyman, at Cult Press. While I have wandered in out of the comics realm over the years, Bryan has continued to fortify the medium as solid literature.

While many readers know him from his early work on 2000 AD (Nemesis the Warlock, Judge Dredd) or for DC Comics (The Sandman, Fables, Shade the Changing Man), Bryan's best works are the original projects where he reinvents himself with each new book. In The Tale of One Bad Rat, he tells the story of a girl overcoming sexual abuse, as well as the history of rats, all with a solid nod to Beatrix Potter in watercolor. Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes, written by his wife, the esteemed linguist Dr. Mary M. Talbot, is the only memoir done as a graphic novel to win the prestigious Costa Book Award. This summer, the five-volume graphic novel series Grandville has been collected with annotations for the images, inspirations, and bits of the real history behind the alternate anthropomorphic world. And Bryan is currently inking the third volume in the Luther Arkwright saga for release next year. We talked about his upcoming books, his process, doing a comic in stone, working with his wife, and some of his own encounters with personal heroes.

* * *

Tasha Lowe-Newsome: So how have you been? Other than super busy?

Bryan Talbot: Well yes, been working seven days a week. We usually go away once a month or twice a month to London or Paris for at least a day or two. I’ve just been home all the time.

I've just been working on the new Luther Arkwright book [The Legend of Luther Arkwright]. I'm trying to go back to the feel of the original one. Which is over forty years ago when I started it. I’m using the same sort of crosshatching technique, which is extremely time-consuming. I’d forgotten how time-consuming it was. As a result I’m months behind schedule. We were hoping it was going to come out in October this year, which means I should have finished it in March, or something like that. I’m still inking it. I’ve got about sixty odd pages to ink. It got pushed back to summer, next year.

Wow. So summer of next year?

So yeah, I'm just trying to get it finished. I think it’ll be finished November, December sometime.

The good news for fans is that this summer the Grandville Integral comes out. That’s all five books plus annotations in a single volume.

The good news for fans is that this summer the Grandville Integral comes out. That’s all five books plus annotations in a single volume.

In Britain it’s called Granville L’Integrale, not "Integral", because all of the other subtitles have been in French. When I finished the last one, I wrote annotations for all five books, which are posted on the website. Dark Horse edited them down for the Integral. The book's over 600 pages. It's a beautiful package, with a nice leather finish cover with gold embossing. One of the ideas for the Grandville books and before, with Alice in Sunderland and others, is to make them nice artifacts in themselves. Because, you know, you need to compete with digital pirates. I’m trying to give, with the Grandville books and my books in general, something that is tactile, something that's nice to own, something that you can’t get digitally.

The original five volumes are lovely hardbacks, solid and beautifully bound. So why anthropomorphic for this series?

For starters, I’d never done anthropomorphic comics before. What inspired it was, after I finished Alice I just happened to be looking through a book by the early nineteenth century French artist Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard. He did cartoons of anthropomorphic characters satirizing social mores, the fashions of the day, the attitudes. And his pen name was J.J. Grandville. If you look online you’ll find lots of his illustrations. I’d had this book about his work for decades. I think since the 1970s. I’d had it out because he was a big influence on John Tenniel, who did the "Alice in Wonderland" illustrations [i.e. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass]. I was putting some of the books I was using as reference away and I started looking through it again. It suddenly occurred to me that Grandville could be the nickname for Paris in a world where it’s the biggest city in the world, a word dominated by France. The very first story just came to me in a flash. It came from Grandville, the artist. That’s why it’s anthropomorphic.

Usually I spend years thinking about my stories, mulling them over in the back of my mind. The Arkwright book that I’m drawing now I starting thinking about after I finished Heart of Empire [the sequel to The Adventures of Luther Arkwright], twenty years ago. There's a fantasy story that I’ve had on my mind for about thirty years, but I’ve still not got it right. But Grandville, the very first one, just came in a sudden flood of inspiration. A week after having it in my head, while I was working on something else -- Metronome I think -- I sat down and roughly plotted it out on a piece of scrap paper. Straight away. In one draft. Then [I] typed it up, the entire book, straight from this draft.

Before, I’d always written a graphic novel by going through thumbnails of each page, working on the dialog and text simultaneously, along with the images. I’d spend hours on each page, going through the whole book, working it out before I ever hit the keyboard. With Grandville I just typed it straight out, skipping the thumbnails. I finished the whole script in five or six days. It was like taking dictation. I could hear the characters talking, visually I could imagine the scenes. I'd just cut out a whole stage of developing a story, something I've done ever since, simply visualizing each page first.

A graphic novel, if you’ve never done one, I can tell you, is a long haul. It takes a long time. So anything that can save time is a bonus. Unfortunately, Grandville is the only book where that’s ever happened to me. All of the other books in the series have taken a lot more thought and consideration, working out draft after draft of structure before typing the script. But the first one just came on in a moment of inspiration, it was incredible.

Like Athena, fully formed from Zeus’s head.

[Laughs] Yeah!

I know you talked about this before, but those who have not heard it, why a badger for LeBrock?

A few reasons. I wanted a character who was working class. I wanted somebody who had the deductive ability of Sherlock Holmes but who was also a bit of a bruiser, who was quite happy to beat the spit out of criminals to get information. I thought a badger suited the sort of character I wanted. He’s very tenacious and fights on against all odds. Badgers are incredibly tenacious creatures.

Another reason he’s a badger is the stripes, the black and white facial markings, they’re like a mask, they look cool. I read Rupert Bear when I was a kid. Bill Badger always seemed to be his coolest friend. I don’t know if you know the Rupert books in America, but they’re very well known over here. When I was a kid my Christmas present every year from my dad was the Rupert Annual. I grew up reading these anthropomorphic comics. They’re similar to Tintin by Hergé. Very clear, absolutely clear story telling. I don’t know if you noticed but the very first Grandville starts off with a murder in Nutwood, which is Rupert’s village. You can actually see in one panel Rupert Bear’s father trimming a hedge.

One of the things I like about Grandville are the “doughfaces”. In anthropomorphic comics sometimes humans are just another animal, other times they don’t exist. But in Grandville they are viewed as an under-developed sort of second-class citizens – rather like we treat groups of people often. They are menial labor.

Exactly. It meant I could address racism and civil rights protests. That thread comes to a head in the fourth one, Grandville Noël, where there's a fascist political party who wants to eradicate the doughfaces. Chance Lucas, a Pinkerton detective over in Europe to bring the unicorn messiah back to justice, is a doughface. He and LeBrock team up. In the beginning LeBrock is just as biased as everyone else, but by the end of it he realizes that they’re equals. Chance Lucas is a homage to Lucky Luke, a famous French bandes desineés character.

That is one of the great things about Grandville – really all of your work, but Grandville especially you can go back over and over always discovering references to other things that may have been missed in the first two or three readings.

I love the process pages that you have up on the website that show everything from pencils to finished artwork. It’s really great to look at and get an idea of how your comics are made. What does a normal workday look like for you?

A normal one? The alarm goes off at nine. Though sometimes I'll wake up at half eight and get up, but usually up between nine and ten. First I do email and sort out anything that needs doing. For example, this morning I scanned and photographed art and artifacts for an exhibition I’m hoping to have at the Cartoon Museum in London when [The Legend of Luther] Arkwright comes out. I had a Zoom conference two days ago with the curator. She has to submit a proposal to the exhibitions board and she needed the material to show them. I’ve got all sorts of things, you know, things like a model replica Arkwright vibro beamer, an Arkwright jigsaw puzzle and so forth - interesting pieces that can go on display along with the artwork.

I have a quick look through the news online, then I'll start working before 11:00 AM if possible. I work 'till about half twelve, then go for a walk. I go for a brisk walk every day, just over four miles. I do it in about 50 minutes. When I get back, we have lunch. I start working again about two o’clock. We always eat at nine so I carry on ‘til then. We used to share cooking but, since Mary took early retirement, she does most of it these days.

This past year has been a little different. I’ve been stopping at about half seven, eight o’clock, because I’ve been working on this prose book for an hour before dinner. Yeah, this guy is writing my biography. [Laughs] He’s an academic, in Beirut, of all places. He was there when that explosion happened. He emailed me straight afterwards, with a picture of his neighbor’s windows smashed out. He’s been writing it using interviews, reviews and articles, but there's stuff he doesn't now, like my personal life and the ins and outs of things, so I’ve been co-writing this biography with him. His name is Jade Y Doumani. He’s a young academic, about 25 and a really big fan. We’ll be trying to find a publisher for this heavily illustrated biography. We finished the first draft about three months ago and I’ve since gone all the way through it twice. I’ve polished it and cut it down quite a bit. It was far too long, about 120,000 words. I’ve edited down to about 92,000. He’s currently going through it.

Keep me updated on when you get a publisher.

Grandville is beautifully layered. I think that one of the real treats of the Integral is the annotations. They show how wonderfully Grandville builds on work that has come before it. It gives increasing depth.

Thank you! Also, I've been plotting and writing another graphic novel which is far from finished. It’s not another Grandville novel as such. It’s a prequel called The Casebook of Stamford Hawksmoor and it’s about LeBrock’s mentor when he was a younger man. It’s set 23 years earlier, at the end of the French occupation of Britain. A proper detective story. It’s going to be very, very different from Grandville. It’s stylistically different. It’s going to be in a watercolor wash instead of computer coloring and [it's] not going to be crammed with Easter eggs. It’s more serious, with less humor than the Grandville stories. It’s just a different sort of story, period. Not much point talking about it much, ‘cause it’s years away.

So you have to finish the new Arkwright and Mary has another graphic novel script ready to go after that.

That’s right. The publisher wants to see art samples for the style I’ll do it in. But I have to finish Arkwright first.

No rest for the weary.

Mary has a graphic novel ready and she’s also written a young adult novel. She finished the first draft maybe about a month ago. She’s only now re-reading it.

How has it been working with Mary?

A lot of people do ask us very often, on panels and things, “What’s it like working together?” And it's just totally natural. I mean we've been together for now for 40 odd years-- actually it’s 50 years next year, which is frightening. Working together has been very natural, like an extension of everyday life. We had been working in two different worlds, you know. But since she took early retirement it's great to be actually collaborating on projects together. It’s really enjoyable.

You know what most collaborations are like on comic books; the writer will do the script, then the artist will do the art. Most superhero comic books are a production line where there’s pencillers, inkers, letterers, etc. Our collaborations are extremely close. As Mary’s writing it, we’re discussing it at the dinner table and so on. Then, when I’m drawing it, I’ll be acting as script editor suggesting to Mary “I think you should change this dialog here,” or “I think that’s too long,” or “We need to break this up into two panels.” And at times Mary’s has suggestions for the artwork while I'm drawing it. So it’s a rare sort of collaboration, sometimes on an hourly basis. I mean I think you only have it in a situation like this, where the writer and artist are living together.

I remember working on Raggedyman with Tony [Hicks, the series artist]. There was a lot of was discussion over meals. Every so often there would something on the page, you know, in the script that he had interpreted really differently than I had visualized it. But usually everything had been well hashed out.

What you said reminded me that sometimes working on [The] Sandman, with Neil [Gaiman], we used to work very closely. We'd be on the phone all the time. Sometimes it was just so last minute he'd be faxing me pages of script as he wrote them. I’d be penciling it and I didn’t know what was happening on the next page. Sometimes when I was drawing the scene I’d make up a background character or something and Neil would see it and write him, or her, into the script. That happened a couple of times. He’d fax me pages of script as I was drawing the artwork and I'd be faxing copies of the artwork to him so he could see how it was going.

But yeah, we’re very close. Often I’ll be saying to Mary, “I think this line of dialog needs to be made clearer,” or whatever. On a couple of the books I’ve written some of the script. For example, sometimes she has a silent sequence and I’ll provide some lines if I think it needs making explicit.

Do you have a favorite project you’ve worked on with Mary so far?

I think perhaps Red Virgin [full title: The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia]. I don’t know. Sally Heathcote[: Suffragette] was extremely good the way it turned out. Because, you know, we collaborated with Kate Charlesworth who did the finished art work. And it was just so well-researched and such a good story, a very important story. I did all the rough visuals and panel breakdowns and indicated the light sources, did the compositions, but very roughly, and Kate did the most beautiful artwork over the top. I think that worked very well. That was extremely popular in Spain, where it's been reprinted seven times and won awards.

Sally Heathcote is a great book. You mentioned Red Virgin, can you talk about that a little?

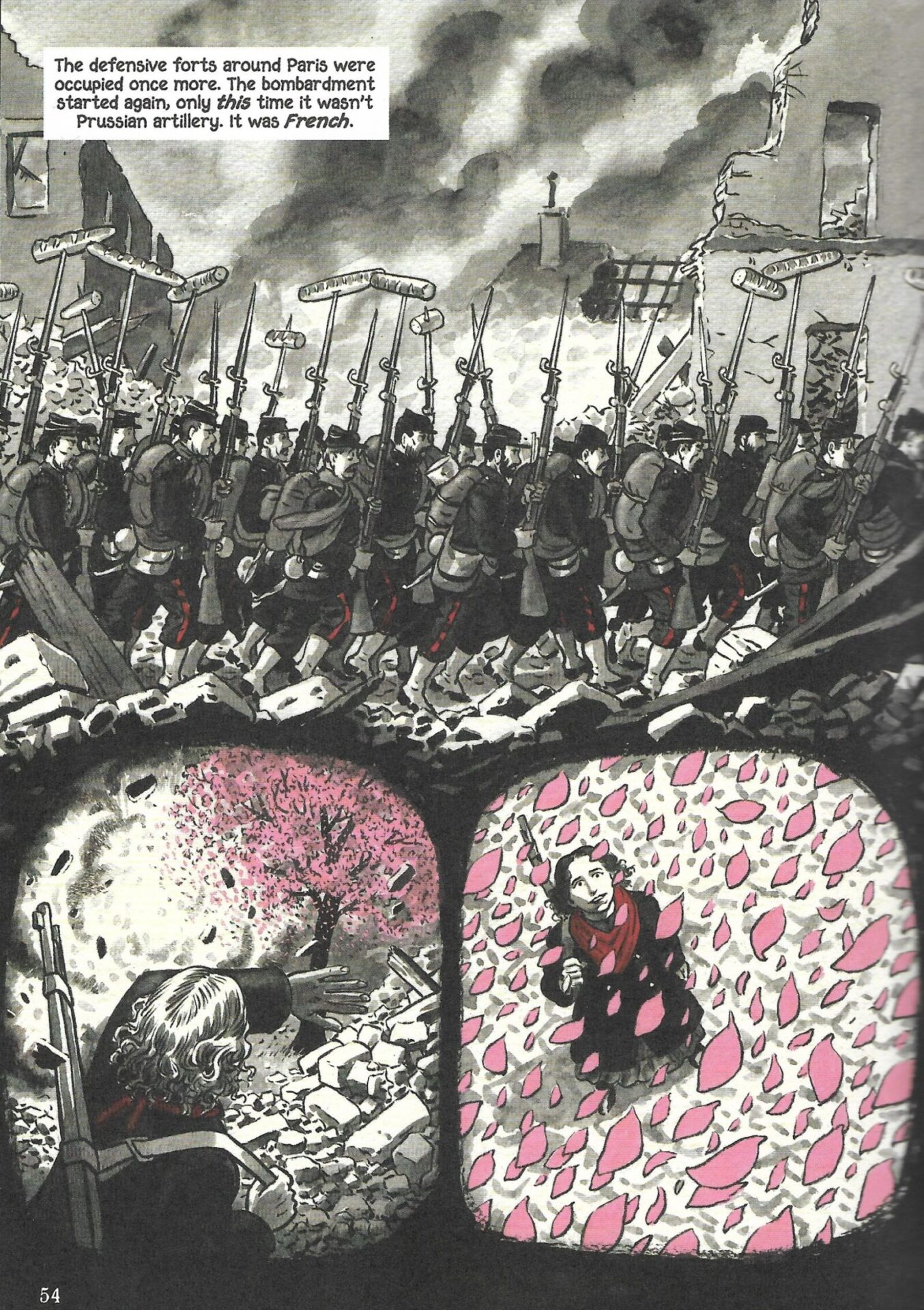

Mary had finished writing Sally Heathcote and Kate and I were working on the artwork and, out of thin air, this hefty book arrived through the post. No note in it, straight from the publishers. It was a review copy, a pre-publication copy, of The World That Never Was by Alex Butterworth. It's an academic study of the origins of the anarchist movement, which I knew nothing about. I thought “Why has somebody sent me this?” I didn’t look at it for two or three months. Then I picked it up one day and started reading the first page and it was really interesting and [I] ended up reading the whole thing. And of course it included the story of the Paris Commune and the role of Louise Michel. Meanwhile, Mary was looking for another interesting female character to base a biography on, so I told her about Louise Michel. “You know, you really must read this book.” Before she did, we were in Paris and were walking past the Hôtel de Ville in the city center and there was a poster outside saying “Free exhibition inside.” It was an exhibition of photographs of the Commune and the siege of Paris by the Prussian Army that preceded it. It was fantastic! Images of the street barricades and things like this. When we got back Mary read the book and naturally she was captivated by Louise Michel. So she then went out and researched everything she could on her. She’s almost completely unknown in the English-speaking world. After Mary read all of the material on her in English she read all of the stuff she could find on her in French. She read Michel’s own accounts and everything else she could get a hold of. That’s how Red Virgin came about.

Years later, after it was published, we were at an event in London to publicize it, and the guy we were being interviewed by was Alex Butterworth, who’d written The World That Never Was. He told me that he'd had a copy sent to me because he was a big fan of Grandville! That’s why I received the book in the first place.

Louise Michel was just an incredible, amazing woman. She was a poet, a teacher and a philosopher, and she corresponded with Victor Hugo and she was absolutely fearless. Absolutely. She was like a secular saint. She had no money at all, but if somebody was cold on the street, she’d give them her shawl. She fought on the barricades. She used to run in front of machine gun fire. She went all through the siege, and La Semaine sanglante ("Bloody Week") -- a huge massacre of the Communards in Paris by the Versailles government -- and she came out of with just a scratch. Incredible. At her trial she demanded to be executed. She said, “You killed all of my comrades. If you’re not cowards, kill me.” They didn’t. They exiled her to New Caledonia on the other side of the world.

An impressive amount of research goes into all of your books, and Mary’s as well. Not just for the story and historic facts, but also visually. Your wealth of sources is really amazing.

I only feel confident if I am grounded in the situation. For Red Virgin we went to Paris to the sites where the events took place. We went to all of the museums we could. It was great that I did, because a lot of them, especially the one in Saint-Michel that had a whole section of the museum dedicated to the Commune, and they have illustrations you just can’t see anywhere else. I’ve not seen them in any books or online. You’re not supposed to take photographs in there, but I did. They have uniforms from the time and weapons and things which I could draw from. Also we went to New Caledonia, which is in between Australia and Fiji. We spent Christmas in Australia and got the plane over to New Caledonia to walk the beaches that Louise Michel walked. We went to the museums there of course. Three different ones.

Yeah I like to, especially with historical stuff, be grounded in reality. I think that’s the only way to do something good. You have to turn yourself into an expert on the subject. For Alice in Sunderland I became an expert on Lewis Carroll and Alice.

You ended up with not one, but two doctorates for Alice in Sunderland, right? For those unfamiliar, it is a 328-page graphic novel that weaves local history and legends with the lives of two famous locals – Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell, all MC’d by a version of Bryan himself.

You ended up with not one, but two doctorates for Alice in Sunderland, right? For those unfamiliar, it is a 328-page graphic novel that weaves local history and legends with the lives of two famous locals – Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell, all MC’d by a version of Bryan himself.

Yeah, honorary doctorates. At the time I was working on it, I was reading dozens of books on Carroll. I joined the [Lewis] Carroll Society and I was conversing with academics who studied him. And after it was published I was awarded two honorary doctorates; a Doctorate of Art from Sunderland University and a Doctorate of Letters from Northumbria University. Basically for doing Alice. It was a bit like doing a PhD. I don’t say that lightly because I’ve seen Mary do one and our friend Dr. Mel Gibson, and I know how much hard work it is, how long it takes. [NOTE: Dr. Mel Gibson is a comics scholar. More about her and her work can be found here].

Art seems to be the family business. Mary went from being an academic to writing fiction books and graphic novels. Your youngest son Alwyn is an artist. He did a few pages in Grandville. What’s he working on these days?

He's a concept artist for videogames. As usual, he can't tell me anything about the game he's currently working on until it's actually out as there's a confidentially clause to protect the intellectual property. He's working on character concepts at the moment. He’s worked on a lot of things. He did the concept designs for the Gladiator game [Gladiator: Sword of Vengeance] and the [2017] Power Rangers movie, of all things. That was a while ago.

Meanwhile, Robin, our eldest son, runs an arts center in Preston. He arranges the gigs and the exhibitions and things like that. He's just started again, now [that] we're coming out of lockdown. Also, he's written a novel. It was supposed to be published last year by an American company. I don't know, COVID happened and it seems have gone by the board. He’s looking for another publisher for it now. He's actually coming over with the two granddaughters for a visit this weekend. Preston’s about four hours from here by train.

Speaking of places that are only a train ride away, can we talk a little about the Lakes International Comic Art Festival? How did that come about? How did you and Mary get involved? And is it going to be live and in person this year?

Yes. Supposedly [this year will be live].

Since the '60s in Britain there have been marts and comic conventions in hotels or conference centers. In the early 1980s I was a guest at the first European comics festival I’d ever been to which was the Lucca Festival [now Lucca Comics & Games, held in Lucca, Italy]. I think it’s the biggest one in Europe now. I think it's overtaken Angoulême. I went there and my eyes were opened. I thought WOW! Seeing members of the public going into the publishers' tent and buying comics. The festival took over the town. It wasn’t just like a bunch of comics fans in a hotel or a center someplace, it was an entire town en fête. I thought wouldn't it be great if we had one of these in Britain sometime! Every time I’d go to Angoulême I’d think, my God, this is absolutely terrific! Angoulême takes over the town for most of the week. There are events everywhere. Finally I tried to get one off the ground here in Sunderland. I went to the town council and gave a presentation about comic festivals and what they’re like and I did get some interest. They assigned me a clerk to coordinate with me and it got as far as one meeting with Paul Gravett, the comic historian, and Dr. Mel Gibson, a comic academic. Then the next week [the clerk] went on to a new job and that was the end of it.

Basically, for decades I've been longing to have a real comics festival in Britain. Then I got an email from Julie Tate, who's a professional festival organizer. She's organized book festivals and ones in the Lake District celebrating the towns. Her son was into comics and through that she got into the medium. She lives near Sean Phillips, the artist on Criminal and lots of others American comics [Sleeper, Incognito, Fatale, The Fade Out] in the Lake District. She asked Sean “What do you think about the idea of having a festival for comics in Kendal?” And Sean said, “Oh, here’s Bryan Talbot’s email. Ask him.” [Laughs] So, I got this email from her asking if I thought it was a good idea. I just flipped. I sent her an email, it must have been a couple of thousand words long, detailing exactly what a European comics festival is like. And she got back to me immediately. I mean that’s what she’s like. She’s a dynamo. Once she gets her teeth into something she’s a marvel.

In the email, one of the things I said was “In January the Angoulême festival happens. You should go some year find out for yourself what a European festival is like.” She emailed me straight back and she'd gone ahead and booked for January. She somehow managed to find a hotel room in Angoulême for January, in November, which is a miracle. They’re all booked up, ‘cause a quarter of a million people go every year. But she’d managed to do it.

This was November. In January 2013 she had me over to Kendal where she gave a presentation to town council, the local college and local business people who might be interested in sponsoring it, and I gave a presentation on what a European comic festival was like and what they could expect. By the end of the meeting they were all jumping up and down saying “Yeah, that’s a great idea, let’s do it!”

The first one happened the following October [of 2013]. Can you believe that? Only nine months later and when it arrived it was fully formed. It’s grown and developed since, but from the very first one it was a proper European-style festival. The main venue is the big Kendal arts center. That’s where most of the talks and panels are. But there are events all over the town. The town hall is where the artist’s alley is, [with] the publishers, booksellers, and there's free exhibitions open to the public, a comic-themed film festival, and events at the library over the weekend. The shopping mall in the middle of the town is the family area, with children’s comic publishers' booths. These are all within easy walking distance. The idea was that the festival covers ALL the world of comics, not just the superhero genre that dominates most comic conventions. There are comics displays in the shop windows on the high street, like in Angoulême. There are banners in the streets. The bat sign flies from the town hall flagpole. And that’s the only time when a flag that isn’t the Union Jack flies there.

Since then it’s developed. The Lakes Festival now has alliances with 25 different comic festivals and comics organizations and we have guests from all over the world. Even the first year we managed to get quite a few guests who Sean and I invited. Since then, they handle invitations and we just suggest people. But the first year we had Joe Sacco, José Muñoz, all sorts of people. Since then we’ve had Jeff Smith, Scott McCloud, Ed Brubaker, Kurt Busiek, lots of European artists, all the top British artists and writers.

And it’s incredible, because Kendal is a beautiful, small, picturesque town. If you do a Google image search you’ll see what it’s like. [The festival is] small enough to take over the town, and get the locals interested. And we do have members of the public going into the town hall (it’s free entry) buying comics. Which is great. Introducing them to graphic novels and comics. Last year, obviously, it was a virtual festival, but it was still very well organized. This year we’re supposed to be having a regular one. Fingers crossed. In honor of how it started, Julie made me, Mary and Sean the three "founding patrons". Since then, they’ve added another four or five patrons. They add around one a year.

The Comics Laureate was introduced at the Festival in 2015. It’s an interesting award.

The Comics Laureate was started around the same time as the festival by a very short-lived charity called CLAw (Comics Literary Awareness). They came up with idea of a Comics Laureate and the first went to Dave Gibbons. When the charity collapsed, Julie took over the Laureate and, since then, [the] Festival's been running the scheme. It’s different from being, for example, the Poet Laureate, whose only job is to write a poem for the Queen once every couple of years. The role is to go around schools and libraries and the like a few times a year to increase awareness about comics. The Laureate isn’t really an award. It’s a function.

I love that the Laureate is an ambassador for comics. It’s also an interesting mix of people, both artists, and the current Laureate, Stephen Holland, is a retailer.

Stephen Holland is evangelical about comics and graphic novels. He can talk about them very well. The first one was Dave Gibbons. After that, I was offered it, but I turned it down. I was too busy. I don't have time to go around talking at school. Besides, I'd feel a bit uncomfortable about it because I’ve always done adult comics. I have done one or two strips meant for children -- I did one for the Fractured Fables anthology -- but on the whole I’ve done adult material so I'm not the right person to talk to kids about comics.

You could always talk at universities.

I do. Frequently. Or I did before COVID - PowerPoint presentations on comic storytelling or about specific graphic novels. I had several lined up in 2020, but I had to cancel, of course. The Lakes Festival hosts the Sergio Aragonés Award as well. We had Sergio himself over for the festival and he presented the first one [in 2017].

Right. The Sergio Aragonés International Award for Excellence in Comic Art. There have been some wonderful recipients – Dave McKean and Hunt Emerson.

On a completely different note, I’d like to know more about the Keel Line and what is was like to work on something to be carved in stone.

It was strange because I was working on Grandville Bête Noire and also doing the layouts for Sally Heathcote at the time. I got a solicitation from the chief architect of Sunderland Council, a mail-out to design studios asking for tenders to be submitted to design a 230-meter-long strip of pavement. They were building a new city square. Sunderland has never had one of any size and they were taking advantage of some sites that had been cleared in the city center. It's called Keel Square. They wanted a strip of paving stones to go across the middle of it celebrating Sunderland’s shipbuilding history, which lasted for centuries. It started in about the 13th century and only finished in 1980. They wanted a list on the paving flags of all of the ships built in Sunderland, at one time, the biggest shipbuilding port in the world. They would supply the list of names. At first I thought, “I don't have time for this.” Also, I hate doing blocks of typography. But the more I thought about it, over the next week or two, the more I thought, “If I don’t submit an application, after it's made, every time I pass it, I’m going to see it and think, 'I could have done better than that'.” (Laughs) So I put together a proposal, submitted it and didn’t think anymore about it. Then I got an email to say I'd won the tender. I couldn't believe it, as I'd been competing with big design studios. But when I went into the architect’s office for the first meeting, when I was called in to talk about it, they showed me the other proposals, and I could immediately see why mine had won. Because theirs all looked boring. They were simply lists of the ships' names and the dates in boring typefaces. They looked like war memorials. I had designed mine so that it started with two asymmetrical coils of rope in the flags to either side of the start of the line that overlap and then continue, acting as a rope border running the entire length of the line of stones. The first rope factory in the world was in Sunderland, supplying rope for the sailing ships. Every 15 paving stones, the ropes cross over each other and, in the two triangles formed when they cross, I drew illustrations telling the history of Sunderland, concentrating on the shipbuilding, starting with the Venerable Bede, the father of English literature, who lived here in the 7th Century. All the way up to 2000 when the town was given city status and built the new Winter Gardens, among other things, to celebrate it. So, yes, mine had pictures and a rope border and the typeface I’d chosen was a nice slab serif face, it looked quite chunky. It looked much more interesting than the other designs that had been submitted.

Then I had to do the thing. Which took about three or four months. Fortunately I didn’t have to do any research because I’d already done it all for Alice. I was an expert on the history of Sunderland, though I did do a bit of visual research on old shipbuilding tools and the like. I had to be very strict about the style I used because the images were going to be sandblasted into the granite. They couldn’t be more than a millimeter or two deep and the lines that I used-- I couldn’t do solid black or anything like that. I had to do individual lines that couldn’t be more than five millimeters wide, because, if it rained during winter, then it froze over, it would be an accident hazard - people could slip on them. So I was very constrained by the style. It's basically a clear line style.

I played it straight. The only thing I managed to slip in was that in the two or three flags about the Second World War, there's one showing servicemen, representing Air Force and Army and Navy and a Wren [or, WRNS, Women's Royal Naval Service], a female sailor. The male sailor in the picture is my dad, based on a photo of him in his Navy uniform; he was sailor in the Second World War. Which was nice, because I could show it to him, a year or two before he died. He was very pleased to be immortalized in granite!

For most people who work in comics, the longest lasting anything gets is a hardback graphic novel, not stone.

In a way it’s like a 230-foot long granite comic strip. Pictures punctuated by lists of ships. I designed the typography, but they got their IT department to lay out the typography for it, which was a relief.

Which brings us back to the new Arkwright and anything that saves time being a godsend. I was noticing the ways that your style has streamlined since the original Arkwright series. You said you’ve gone back to that heavy crosshatching.

Yeah, I’ve gone back to the old Arkwright style.

You have made a lot of stylistic choices over time. I’m thinking about The Tale of One Bad Rat being watercolor, Sally Heathcote: Suffragette being very limited color, Heart of Empire in full computer color. How do those choices get made? Is it dictated by story, by publisher?

It's always dictated by story. I always spend a lot of time thinking about what sort of style suits the atmosphere of the story. It’s part of how you lay it out. The art you use is part of the storytelling. So the style has to suit the story exactly.

The last book I did with Mary, Rain, is about environmental issues. It’s set in an imaginary version of Hebden Bridge, a village in Yorkshire. We went there several times, staying at a local pub for a couple of days. We walked the moors. These are the same moors where Wuthering Heights is set. One thing I noticed was how vast the sky is, how wide on the top of the flat moors. I said to Mary, “This book has to be in landscape format” to display these wide vistas. It’s the only book I’ve ever done in that format, I usually use portrait. That was a stylistic choice, inspired by the place where the story was set.

I also love that that book is bracketed by some really interesting historical environmental awareness that goes back to the 1800s – which is phenomenal.

[Alexander von] Humboldt was centuries before his time. He was saying to people, “Look, you’ve got to stop burning all this coal or the planet is going to warm up and you’ll have a disaster on your hands.” He was saying this 200 years ago.

So Grandville has a certain amount of politics and political awareness in it. You say you check the news daily. Do current events continue to inspire or...

They dismay me usually.

What are some of your favorite overarching themes?

[The Adventures of Luther] Arkwright was written against the background of the rise of the right in Britain, the Thatcher government coming to power and the National Front, a fascist organization, marching on the street. It’s one of the reasons I’ve gone back to Arkwright today. Because the far right is on the rise again. It’s like the 1930s, almost the same atmosphere, and you know what happened then. The new Arkwright story is anti-fascist and anti-nationalistic. It’s showing the evils of extreme right-wing thought.

I have a very long sequence, actually nothing to do with that, set on a parallel world where a plague decimated the vast majority of the population in 1943. [Laughs] I’d actually scripted and penciled it before the Coronavirus pandemic started. People are going to read it and think it's inspired by COVID. I’d actually been thinking about the sequence for quite a few years. There’s nothing new about plague stories, but they are usually set when the plague is actually happening. This is set a hundred years after plague has virtually wiped out most of Britain. I thought it would be interesting to imagine what the country would be like after all that time. It’s like the Dark Ages. We still haven’t recovered. When I say decimated the population, I meant it nearly wiped it out, not just one-in-ten. It only left a couple of thousand people alive in Britain and their descendants are still clawing their way back. What was interesting for me was to show towns and villages and roads reclaimed by nature, trees growing in the middle of them. The houses are all falling to pieces, they’re shells and people are grubbing for existence. The country is splintered into small kingdoms, with robber barons and warring tribes.

When you say utopian and dystopian worlds you weren’t kidding. How was the process of turning the original Arkwright series into an audio story?

I didn’t do the script. It’s a good production. David Tennant plays Luther Arkwright and Paul Darrow (from Blake’s 7) was Cromwell. My only criticism is that the script stuck too close to the comic. I’ve only listened to it once all the way through - it’s three hours long. Listening to it, I wasn’t sure if anyone who hadn’t read the graphic novel would know what was happening at certain points, because the script is almost literally line for line from the book. While you can write something in a comic that seems naturalist when you read it in a speech balloon, in context in a comic, if [it's] said in a conversational manner it doesn’t seem as naturalistic and realistic. I felt it would have benefitted by being adapted more [for] the medium of an audio drama.

They’re recording the sequel, Heart of Empire right now, and I did point this out to the guy who’s scripting it and told him to feel free with his adaptation. David Tennant has reprised his role as Luther Arkwright and has already finished recording his sequences.

Excellent. Looking forward to that.

Another piece of Arkwright news is, of course, I’ve just sold the option for a TV series. Although, I’ll believe it when I see it, because I’ve just gone through four years of this with Grandville. [Grandville] was optioned by Euston Films, part of Fremantle, who are quite a big outfit. They had the scripts written but didn't manage to get anything off the ground. I shouldn’t complain, really, as they paid me once a year to keep the option. Anyway, my agent is now trying to show it to other producers, so perhaps something will come of that.

I thought their vision for it was great. It was going to be live-action, with CGI for the animal faces, the automatons and effects, etc. They had Sarah Greenwood on board as production designer, the woman who worked on the Robert Downey Jr. Sherlock Holmes films, which would have been just the right look for Grandville. The writer was a Doctor Who guy, and I’m sure he did a good job. It’s such a shame that nothing happened with it.

With the Arkwright option, is that planned as live-action?

Yeah. Their idea is a Game of Thrones-style adaptation.

That would be phenomenal. I think one of the advantages of this time in filmmaking is the technology has caught up with the work to be adapted. That seems to have opened the imagination of people with purse strings.

Mmmm. I hope so.

Is The Tale of One Bad Rat still being used in child abuse programs?

Is The Tale of One Bad Rat still being used in child abuse programs?

I don’t know if it still is. It’s still in print, so it may be. I’ve been in six different countries over the years, where people have told me it is used there in abuse survivor centers. I do still get messages from people about it. It’s been published in around 16 countries. I think it’s probably the book I’m most proud of, not just for the fact that I still get people contacting me about it, saying how much it means to them, how it’s their favorite graphic novel and how it helped them deal with their experiences. I’m just very pleased with the storytelling and the story itself. The writing in it, I think it was a big step up for me. The artwork I’m very pleased with as well.

Congratulations on The Tale of One Bad Rat finally getting an option for the big screen. Anything you can tell us about who's behind it, what the plans might be or when it might get the actual green light?

There’s not much to say about the Bad Rat option at the moment. The small British production company is Grasp the Nettle, who are currently in the middle of shooting two films, and will only be starting on Bad Rat (I hope!) when they are under wraps, so there’s not much to say about it.

I think by this time you are an influence on loads of people, especially creatively. Who would you say are your biggest influences?

Mine? Moebius, Robert Crumb, William Hogarth, Gustave Doré, Alfred E. Bestall. Jack Kirby must have been huge influence on me. I used to read all his stuff. Leo Baxendale - I know mine doesn't look anything like his style, but he was a hugely popular British children’s humor comics artist who used to do fantastic illustrations, packed with detail. Loving looking at all of the detail in his pictures, I think that stayed with me.

You’ve got to love looking at illustrations. And, if you do, illustrations are great, but comics are even better - every page has dozens of illustrations, hundreds in a graphic novel. And they aren't just disparate illustrations; they all come together to tell a story. For me that’s part of the fascination of comics - a sort of alchemy happens in your mind, when the pictures and words come together to give the impression that the story is flowing before your eyes. That is the magic of it for me.

Absolutely. Sometimes it just draws you in. Sometimes it’s counterintuitive. I’ve noticed that I still come across manga that have a great little diagram showing the order in which you are supposed to read the panels.

When I was working on Teknophage with Rick Veitch we did a whole issue told in a series of double-page spreads. Where this guy is trapped in the office from hell, the desks and workstations receding into the far distance. Rick wanted to get the feeling of this guy being caught like a rat in a trap. He came up with the device of having the text box in every panel connected to the next by a little gutter, a white line that connects them. So I could make the panel layout of the spreads counterintuitive, going the wrong way, up and down, all over the place. In one spread, we even had the panels as a spiral, ending in the middle. And it's still very easy to follow because you just read one text box and followed the gutter to the next, leading the eye where it didn’t expect to go, which was quite clever. It was Rick’s idea.

That’s brilliant. A lot of Rick’s work breaks norms.

It is amazing what stays with you from childhood. Leo Baxendale’s work drew you into viewing art a particular way. In part that led to an amazing career and influenced your style.

The fifth Grandville, Grandville Force Majeure, is dedicated to Leo. He died while I was working on it. I read all of his comics when I was a kid. I just loved them. Later on he became a great friend after it turned out he came from Preston, where we lived. You know, the house where you visited us in the '90s. He used to stay with us when he came up every few months to visit his mother before she died, so we got to know him very well. He was one of the three artists who reinvented the British children’s humor comic during the '50s. Leo, Ken Reid [of Roger the Dodger] -- who was a massive influence on Kevin O'Neill -- and Davey Law [of Dennis the Menace].

The afterword of Grandville Force Majeure talks about Leo. It also talks about my grandmother who was big influence on the character of LeBrock. [Laughs] She's in Alice in Sunderland too. My maternal grandmother was [a] real tough working-class woman. When I was 16 she called me over and gave me a pair of brass knuckles. [Laughs] She’d carried them in her apron pocket for forty years.

When you work do you tend to listen to music or do you like it quiet? Is there a soundtrack? Is it different for Arkwright and Grandville? Or is it just what’s on the radio today?

No. If I’m writing or penciling, I need complete silence. I don’t want to be distracted by anything. However, if I’m inking or coloring, I find that uses a different part of my brain and I can listen to stuff and do it at the same time. It’s a bit more mechanical I think. While I’m inking, I usually listen to French radio. Or there’s a lot of French material on YouTube, everything from stories to grammar lessons. So I’m sharpening my French all the time.

In fact Mary and I were in France last year -- October actually -- right in the middle of the epidemic. We were guests at the Festival de la Bande Dessinée de Bassillac et Auberoche and there was a big exhibition of artwork based on the Paris Commune, including 40 pages from our The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia. We actually did the Red Virgin PowerPoint presentation and a question and answer session afterwards, all in French, without notes and without an interpreter. It's the second time we’ve done it. We did it a year or two ago at a festival in Arras. I’ve been learning French for several few years.

Before I let you go can you give me a little teaser about The Legend of Luther Arkwright?

It takes place about 50 years after Heart of Empire. The plot sees Arkwright pitted against a far superior adversary, a highly-evolved being on a quest to eradicate the destroyer of the planet – Humanity. It takes place over several distinctly different parallels, both dystopias and utopias.

Other than Luther, will any other favorite characters be making appearances?

Harry Fairfax and Rose Wilde are back, of course.

I am looking forward to the collected Grandville and waiting like mad (like everyone else) for the new Arkwright. Not to put any pressure on you. We’re all very excited. Godspeed on all of it.

Thank you and hopefully we’ll talk again soon.