If I had my way, Richard Short's comic Klaus, would be syndicated in the daily papers for everyone to enjoy. Funny and poetic trials and tribulations of a feckless anthropomorphic cat, just what you need with your morning coffee. Thankfully, Breakdown Press have been publishing the stories of this sad, murderous cat-man for some years now, and have just released Haway Man, Klaus! Short's biggest collection to date. Unfortunately UK Covid restrictions have put a stop to Richard hosting a proper book launch, but we can instead pretend this interview is taking place in the tiny back-room of an East London comics festival. I'm struggling to get the laptop to display the slides on the projector, there's still some standing room at the back there...

If I had my way, Richard Short's comic Klaus, would be syndicated in the daily papers for everyone to enjoy. Funny and poetic trials and tribulations of a feckless anthropomorphic cat, just what you need with your morning coffee. Thankfully, Breakdown Press have been publishing the stories of this sad, murderous cat-man for some years now, and have just released Haway Man, Klaus! Short's biggest collection to date. Unfortunately UK Covid restrictions have put a stop to Richard hosting a proper book launch, but we can instead pretend this interview is taking place in the tiny back-room of an East London comics festival. I'm struggling to get the laptop to display the slides on the projector, there's still some standing room at the back there...

Richard! for the benefit of North American readers, and those not versed in North Eastern dialect, what does "Haway Man" mean?

The Evening Chronicle, a local newspaper, defines it as: "a generic proclamation of exhortation or encouragement, which can be both positive and negative". It can be used to mean come on, go away, good luck, shut up, hurry up or okay. So the full range of responses a frustrating figure like Klaus could receive.

What was your impetus to create Klaus and the other creatures that inhabit his world?

What was your impetus to create Klaus and the other creatures that inhabit his world?

About a dozen years ago I was training as a lawyer - I'd drawn very few comics and found them a bit daunting. Without much planning I started doing a 4-panel strip each night after work. I can’t remember why I started, but it must have been because of Peanuts. I’d read Schulz’s panels were 6.5 x 5.5 inches and that’s how I drew mine. Looking at the Nobrow book from 2011, the Klaus character was there from the start - a lonely 'little man' overpowered by his emotions. A few of the other characters are there too - the disapproving rat chorus, Klaus's pompous doppelganger Otto, and Lovely Horse, Klaus's unrequited love. Being able to complete a strip every evening was very appealing and it felt quite natural, probably because I'd ingested so much Peanuts and Andy Capp (which is also set in Hartlepool). It seemed quite romantic too, a daily strip and a recurring cast of characters.

So a daily drawing challenge, a bit of routine? a way to air thoughts and ideas?

I suppose it was about routine - laying out some structure, a set format with a core cast, through which to air daily thoughts and ideas. Mulling over a joke throughout the day and then drawing it at night, and letting the strips slowly build into a book. I wanted to do comics and a 4-panel strip was a way in. I just never moved on.

I can't believe that was ten years ago...how have things changed over that time? Do you still enjoy giving these characters life?

I looked at the first book again for the first time in years tonight and aside from the drawing I still quite like it. I think there's just a higher incidence of botty-curdlers in the older books - ones I wince at for being clunky or pretentious. I have a backlog of undrawn strips and I've been drawing a daily strip again this year. I still really enjoy giving these characters life, and they've changed and been added to over time. It would be a radical change in my life not to be drawing this strip.

I'm interested in this process. Have the cast established themselves enough that they lead where a story might go? Like, are you writing or are they?

I'm interested in this process. Have the cast established themselves enough that they lead where a story might go? Like, are you writing or are they?

Getting into very luvvie territory here, or an admission of mental illness. There is an element of being led by the characters, in that by having a dozen often-used characters it means that every idea I have I can match to one of the characters, often while I'm having it. But I'm not thinking in character - I'm not a writing hand for my inner alcoholic Aylesbury. They don't sit within me and scream out lines. When I'm reading I never think "That is sooo Klaus" or anything. But I have a pad to note ideas and phrases and then a few pages later I might sketch out a strip (1-, 2-, 3-, 4-) - just the text usually - and I might write a character's initial against the text, but the text changes and the initials might change before I come to draw it.

I also never think "I want to explore jealousy/aging/realzsing you have no talent" in this next story arc, but I might have some thoughts about aging I can turn into strips, and they might sit alongside some others about jealousy and they might come together later on. The themes and the story emerge that way - slowly building it up and changing the focus as it goes.

To what extent are Klaus and Otto autobiographical? Is this all a clever twist on the classic sad-boy-diary-comics genre, with the characters representing parts of your psyche?

Klaus isn't obviously autobiographical - he's a semi-rural shiftless ponderer with a destructive unrequited love, whereas when I drew most of these I was working 9-to-5 in London and in a long-term relationship. But I have an inner Klaus and an empathy for all the characters - I'm not just the sad, deprived and pompous cats, but also the aloof, sexualized mare; the suicidally-morbid mallard; the bigoted, resentful rodent. I haven't read many auto-bio/diary comics, maybe only Dirty Plotte, but I obviously love Schulz, and a lot of other sad boys, like Cavafy, Larkin, Walser, Denton Welch.

You moved from the North-East to London early in Klaus's creation, so you've been down here ten years, a fair chunk of your life... How important is the location to the work? How important is Hartlepool?

You moved from the North-East to London early in Klaus's creation, so you've been down here ten years, a fair chunk of your life... How important is the location to the work? How important is Hartlepool?

I started drawing Klaus about a year before I moved to London, but the setting - the semi-rural, ex-industrial Teeside coast - remains important and the strip's mood has been pretty consistent. There's a lot of background in the strips - sometimes it might look more like Scotland or Greece than Hartlepool, but the sense of an isolated, deprived, thinly populated place (with the North Sea looming over it) remains important. The whole mood is determined by the setting, at least in my mind. Reg Smyth left London as soon as he could and moved back to Hartlepool, so he could soak it all up for his strip – the look of it and the way of talking. My strip's Hartlepool is more of a Hartlepool-of-the-mind, so I don't have to live in a tree on a wind-swept beach.

Harry Pearson, a sports writer I really like, explained this about Teeside, in relation to its neighbor, Tyneside: "Tynesiders are remorselessly cheerful. The average Geordie is so upbeat and optimistic that if you put him in a pot and boil him down to his very essence, the substance left would be Prozac… I’m from Teesside. Teessiders are by nature pessimists. If you put a Teessider in a pot and boiled him down to his very essence, he wouldn’t be a bit surprised."

Ha, that's excellent. I love the way locals are often depicted as grotesque caricatures existing only on a plane, in the foreground in front of the action, or to the back, part of the backdrop. It puts me in mind of a cardboard theatre. Often I see your panels working this way, two dimensional, but with several fields of play.

Ha, that's excellent. I love the way locals are often depicted as grotesque caricatures existing only on a plane, in the foreground in front of the action, or to the back, part of the backdrop. It puts me in mind of a cardboard theatre. Often I see your panels working this way, two dimensional, but with several fields of play.

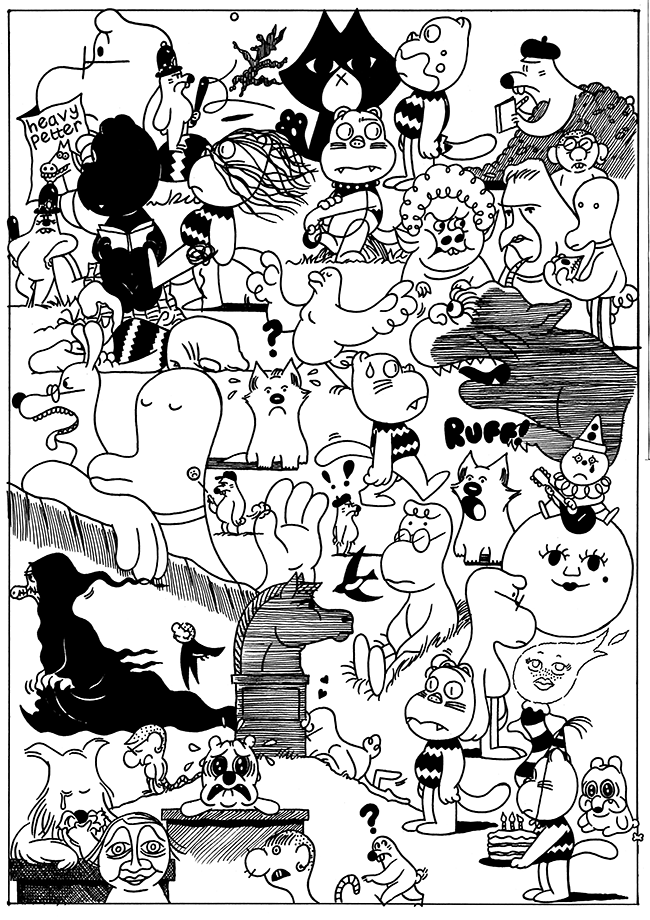

That's good - that's how I often think of the panels, like shoebox dioramas or a table-top animation set - an Ivor Wood-type thing. I really like doing those grotesques - clogging up the front of the panel or wandering drunk in the background. I didn’t think I thought about it much, but loads of stuff I loved had grotesque extras - The Beano (especially Leo Baxendale, Ken Reid and Tom Paterson), Lowry, Grosz, Ensor. It seemed a very comics-y thing to have all those deranged extras in the margins.

Your influences come from a broad church, it's something you've covered in the past in the letters page of Klaus Magazine, so we don't need to go into it here. And I'm sure you're sick of the same old Schulz, Jansson, Herriman comparisons. But I am interested in your schooling, how you became such an accomplished cartoonist. You say you don't like the drawing in those early comics, but to me it seemed like you hit the ground running, with a really strong visual language, a wide cash of cartooning language already under your belt. And all the while training and working as a lawyer. It amazes me. Maybe I'm just used to most of us working in education or low skilled work to pay the bills. Anyway I'm jabbering on, I forgot what the question was? training? how you've honed your craft?

Thanks Joe. I stopped art education at 16 but I was always drawing up to that point, so much that my parents were a bit concerned. I was creating very elaborate worlds, based around football leagues on other planets, with illustrated club histories and drawings of every current player. The drawing was based on crappy cartoons, like Heathcliff and Teddy Ruxpin, The Beano, SNES booklets and magazines and then briefly in the early 90s magazines like Anime UK and Manga Mania, which my dad would drive to another town to buy. They stopped stocking them as I was the only buyer.

I don't remember drawing much from 16 until about 24, when I bought Kramers Ergot 5 and then I bought a flood of comics off the back of that and just started drawing loads again, but this time centered around comics. I had a few comics published by a German anthology, Two Fast Colour, while living in the North East, and then the first Klaus book came out when I was almost 30 and had moved to London.

If you're going to dip your toe in any comics, Kramers was such a good call. Such a diverse selection. And through your Nobrow book you got to know the Breakdown Press gang, who, I feel, publish similar work to that of Alvin Buenaventura or Dan Nadel. Does it come under the banner of Alt Comics? I'm never quite sure of categories but it feels like there's something grouping likeminded publishers and artists... akin to an art movement, or a collective. Say within the Breakdown artists, do you have a shared sensibility? or aims with your work?

If you're going to dip your toe in any comics, Kramers was such a good call. Such a diverse selection. And through your Nobrow book you got to know the Breakdown Press gang, who, I feel, publish similar work to that of Alvin Buenaventura or Dan Nadel. Does it come under the banner of Alt Comics? I'm never quite sure of categories but it feels like there's something grouping likeminded publishers and artists... akin to an art movement, or a collective. Say within the Breakdown artists, do you have a shared sensibility? or aims with your work?

I don't know - it seems to hang together well, Breakdown, but it's a pretty disparate group, aesthetically. I couldn't speak for sensibility or shared aims. Like if you think about RAW you have an idea of what that is, but that had everyone from Mariscal to Tardi in it - it's a strange spread.

Yeah, you're right, perhaps I'm romanticizing it, imagining hotbeds of discourse and underground art in East London, Brooklyn and Berlin... How about you and Joe [Kessler], you've been collaborating a bit over the years, at Angouleme, Ivor Magazine and with your book design, could you talk on that?

Yeah, usually I go to Joe's most weekends and there's a lot of comics talk and looking through Joe's new book purchases. We actually do share a sensibility, in terms of what comics and art we like. Doing Ivor Magazine with Joe was great - we've done a couple of comics together in the last few years, for the Breakdown/Lagon Revue book Dome and then Lagon's Gouffre, and Ivor included the latter and various other pieces - some we did together and some separately. It felt like doing a sort of psychedelic Klaus album, with Joe as the Producer doing most of the work. We'd like to do another one this year, I think. Joe also helps with the book design for Klaus - entirely with the practical stuff and also with the design, which we both like to be quite simple and as bold as poss. Japanese book design has been a big shared enthusiasm.

I loved those Suiho Tagawa ‘Norakuro’ books you told me about, need to get some of those. So, you aim for simple and bold with the book design, which I think is reflected in the comics too, there's a uncluttered feel to your panels, enough elements to hold the gaze, to tell the story, but no unnecessary bumf. And the same with the speech, no more than a handful of words each panel. Are these conscious decisions? do you refine and edit, trim things down? I enjoy the pauses, the pace.

I loved those Suiho Tagawa ‘Norakuro’ books you told me about, need to get some of those. So, you aim for simple and bold with the book design, which I think is reflected in the comics too, there's a uncluttered feel to your panels, enough elements to hold the gaze, to tell the story, but no unnecessary bumf. And the same with the speech, no more than a handful of words each panel. Are these conscious decisions? do you refine and edit, trim things down? I enjoy the pauses, the pace.

Yeah, I think the art has to complement the idea, the jokes - it needs to be easy to read. I think the earlier strips are a little wordier. You want to be able to guide how the panels are read, although I'm not at the Nancy stage - it's much sloppier than Bushmiller's approach. I do quite a bit of editing on most ideas I write down, before they are drawn, sometimes weeks or months later. A fourth panel punchline might appear too obvious on re-reading, so that might become the third panel and then something else is added in the fourth. Or some text might become a wordless panel, because it's funnier to have silence. I've got a little blue jar, about 2.2 inches round, which I draw most of the speech bubbles with, so the text usually has to fit within that jar.

Necessity is the something of something. I think it's a good thing, no one wants too many words. Perhaps I'm guilty of reading your work on a superficial level. The poetic, literary elements sometimes go over my head, but that doesn't detract from my enjoyment. It's something I admire, the not dumbing down. To what extent do you think about audience?

I'd like as many people to get as much from the comics as possible, and there's no intention to be oblique or puzzling. Hopefully it's the characters that come across as high-flown, not the author, but I suppose you risk that when you're using language that isn't necessarily spoken language. The language is intended as part of the color of the strip, and the humor and personality of the characters - their melodrama, their great intentions, their intellect put to little use. It's part of the fun of making it, at least. I think that in most of my favorite comics - Milt Gross, Herriman, Ben Katchor, Schulz to an extent - it's the poetry of the language that holds me as much as the drawing. So when I'm doing these strips I'm probably just thinking of myself - as per.

Fantastic. And they do have broad appeal. What's not to enjoy about a melancholy cat brooding over a spurned horse lover. Everyone in my house agrees.

Haway Man, Klaus is your longest book to date. And although there is a linear storyline, it doesn't seem vital to follow it. A character might die but this doesn't stop them appearing in future stories. There's a real comfort in that. Time almost stands still in Klaus's world. It's perfect toilet reading. What are your thoughts on longform narrative compared to these short strips?

The story in Haway Man, Klaus is very loose and that comes from drawing 220 strips over a number of years with no real idea of the story, just drawing individual strips as they come to me, and then editing it together at the end. There's various threads and various things develop, but the narrative isn't particularly important. I doubt that process will change for this strip - I don't like too much forward-planning. And yes, there are two dead characters in this book, plus Death, and Ivor the rat was disemboweled by owls in Ivor Magazine but has made a full recovery for this one.

I've filled two notebooks with research for two long stories, one about Hadrian's Wall (the Roman wall in North-East England) and one about Bologna in the 1930s, and how sport was co-opted by the Fascists, but I haven't done anything with those yet. The idea of a longform comic seems very daunting at the minute - a proper slog compared to knocking out one-off strips on an evening. I've also written a number of folk stories recently, which might be turned into comics or just collected in a prose book, and actually Joe Kessler has done a really long, 200-odd page comic very loosely based on one of them.

Two new books! One about the building of a giant wall to divide countries and another about the rise of fascism? Haway, Richard.