Digital communication technologies continue to transform the analogue arts to fit into an ever-growing online media landscape. While much of the conversation surrounding them is centered around social networking and media platformization, along with their effect on the average netizen’s social and creative life, web media has found itself reshaping the way audiences interact with art ever since the earliest days of the web. The Internet has allowed the proliferation of fully online and digital-form media that evolved along with it and the communities surrounding them for all of its history; and comics, more so than any other medium, have gone hand-in-hand with the Internet since before there was an Internet as we understand it today, in the form of webcomics and comic strips: arguably the medium which has, historically, been best suited to fit every iteration of the web, and every space that sprang from it.

Webcomics have evolved reflecting the ways online culture and communities shifted over time as online spaces grew in size, audience and complexity. Since their inception, they have provided a window into the possibilities of web media in general. Even from an early stage, their potential to reshape established comic narrative and design have been at the center of the discussion surrounding them. To this day, however, no single webcomic has managed to more completely encapsulate the potential of digital design and presentation than the collected works of Andrew Hussie’s MS Paint Adventures, a sprawling group of interactive, multimedia comics which managed to use nearly every affordance of web media for its own unique brand of cooperative storytelling and quirky storytelling.

To understand the way webcomics can break away from the traditional mold of comics, it’s important to look at the history of the medium, and how its growth was informed by the growing audiences and communities surrounding and sustaining them.

One of the problematic aspects of looking at webcomics from a historical perspective is the lack of writing and archiving of their history and academia as a medium; leading to much of webcomics’ history existing as hearsay and anecdote, with few sources attempting to craft timelines of the medium. For instance, Shaenon Garrity’s (2011) essay The History of Webcomics, published for the online edition of The Comics Journal, outlined a timeline of major webcomics and trends in the medium since their inception in the mid-'80s and onwards into the present. Some years later, Sean Kleefeld’s (2020) book Webcomics did much of the same work within its first few chapters.

Garrity and Kleefeld both drafted a timeline from the very early online comics of the '80s and '90s pre-web era of the internet through to web-hosted comics and professional cartoonists making the shift from print to online publication roughly around the same time as the dotcom bubble of the late '90s, and from there into the present. According to Garrity’s research, the earliest webcomics were hosted in bulletin boards, e-mail mailing lists and Usenet groups, some of which remain difficult to locate and archive to this day. Kleefeld’s timeline mirrors Garrity’s, though he addresses the way in which most of the early history of the medium is apocryphal - the earliest webcomics were mostly passed around in groups of tech enthusiasts or academics, and mostly discussed in a manner similar to newspaper strips. Because of this, along with the non-existence of web hosting in the early days of the Internet and a general lack of archiving of the early web, many assertions about the earliest webcomics remain fuzzy at best and highly unlikely at worst, as Kleefeld points out using the commonly held belief that a comic strip named Witches and Stitches was the “first” webcomic, despite no evidence of its existence remaining available anywhere online.

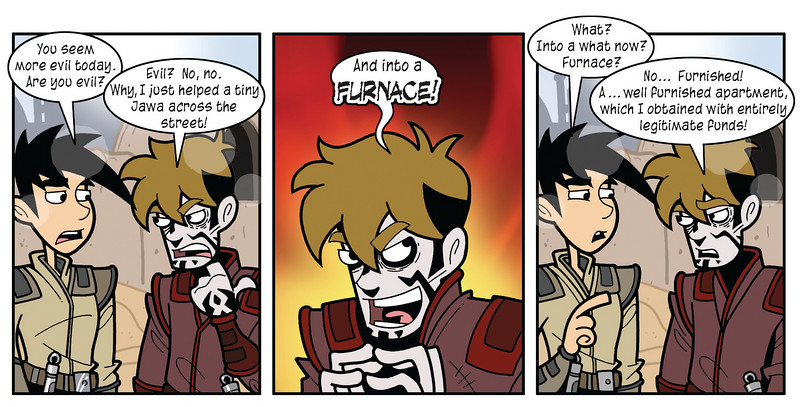

Some of the earliest professional artists to dip their toes into online distribution were established comic strip cartoonists such as Bill Holbrook and Scott Adams, in the latter half of the 1990s. Comics covering a wider range of topics and genres also started to emerge around that time, and web cartoonists started to experiment with the format and presentation of the comics themselves. Garrity herself refers to this period between 1996 and 2000 as a “singularity” of sorts, as the medium was infused with a renewed creative energy from the many writers and artists taking an interest in web publication. It’s around the year 2000 that the popularity of webcomics begins to massively boom, as internet adoption becomes more widespread. Specific genres of comics also become more prevalent; video game, fantasy and science fiction webcomics start to become the most popular around this time. Jerry Holkins’ and Mike Krahulik’s Penny Arcade (figure 01), which began publication in the late 1990s and continues to this day, is one commonly cited example of a webcomic that caught the early wave of attention towards the medium by the growing online population at the turn of the millennium.

An aspect of Penny Arcade’s ongoing success that hasn’t been explored in much detail is how it also provides a good example of successful community building through its long-running forums. Webcomics, perhaps by design, rely almost entirely on building strong communities of fans to keep traffic flowing. However, online community building isn’t just exclusive to the audience, as online creative spaces began allowing for the creators and writers themselves to form their own creative communities over time. In her article, A Historical Approach to Webcomics: Digital Authorship in the Early 2000s, Leah Misemer (2019) discusses a specific mock-feud between the creators of two major webcomics, Questionable Content and Sam and Fuzzy, as a way of exploring the creative environment in webcomics at the time.

At that time, web search results were indexed based on external links to a site. Thus, by serving links to each other’s websites, both authors provided slight bumps in search engine results for their comics, potentially bringing in more readers. Misemer argues that this shows the development of a culture of cooperative competition between web cartoonists, in which it becomes common practice to boost the visibility of fellow authors. From a creative standpoint, this means that artists and writers began forming communities both within and without their audiences over time, as well as with each other. Webcomics like the aforementioned Questionable Content or Penny Arcade would host forums for users to discuss topics related to the comics or other media, keeping users engaged and spending time in the site without having to create new content. These sorts of communities, however, did influence the comics they formed around.

Another effect of this community building is that it gave authors a direct line of communication to their audience and vice versa, thus allowing for the writers to drop in and casually discuss their comics with readers, who, in turn, would end up influencing the comics either directly by suggesting topics to cover or jokes, or indirectly through discussion.

From here we can glean that community, audience interaction and the immediacy of online social spaces lead to a more diverse creative environment, where authors are able to use not just their voices in their stories, but those of their audience and fellow creators, fostering an environment of creative cooperation and competition. This, however, is all related to context around the comics themselves, rather than their content, format and presentation. While community building may be a central aspect to how webcomics are written and how they grow their audience, it’s the way they’re presented and how they use web-based technologies that really sets them apart from their print counterparts.

What appears to be the first academic text discussing webcomics as a unique medium separate to print is Scott McCloud’s (2000) book Reinventing Comics, a follow-up to his previous Understanding Comics (both of which are presented as long-form comic books), in which he goes on to discuss the evolution of comics, multiple revolutions happening within and without the industry, and finally culminating in the development of the digital comic separate from the print format.

In the final chapter of the book, McCloud looks back upon the relationship between home computers and comics, and how the changes in technology bent the then rigid definitions of “comic” that he had been working with previously. The thing that separates the comic from other forms of media is the artist and reader’s agency in the progression of time in the narrative, where panel arrangement and composition turns the comic page into a “temporal map”, time in motion through snapshots of movement. The problem is that up until that point, comics were bound by the standard print page format, which invariably breaks the flow of time and movement within the page, limiting the author’s use of this temporal map and creating conventions in panel distribution and layout that comics follow, and an artist’s available set of tools by proxy. McCloud argues that, at the time of writing, online technology had the potential to “free” the artist from the boundaries of the page, allowing them to work on what he dubs an “infinite canvas”, an endless expanse of non-physical space in which to place panels and display actions in time.

Unbound by the page, McCloud posits that comics could take on any form an artist can imagine, the only limitation being the technology of the time. Bandwidth in the pre-broadband era of home Internet was too low to transmit large images and screen resolutions too small to display them, and the HTML programming language didn’t allow for a zoom and pan functionality, creating many of the same limitations as the page space would. He also makes mention of comics and graphic novels such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus which briefly experimented with distribution on CD-ROM. What is interesting about these CD Comics is the amount of multimedia material they included – Maus, for instance, included photos and videos as supplementary material, similar to how DVD movies would include bonus features a decade later.

McCloud’s argument calls upon the use of web tools such as hypertext and embedded multimedia to not just compliment and accompany the comic, but become a part of it just as ink and paper are. He uses all of this to make a call to action for future comic creators in the digital environment to make full use of the multimedia tools inherent to the online environment and reinvent comics in a way that’s unique to the digital tools now available – calling a joining of comics and interactivity a necessity in its evolution. Interactivity, in all its forms, would become pivotal to the development of webcomics at the turn of the millennium.

Interactive comics have their roots in the mid '90s. McCloud, Kleefeld and Garrity all cite one of the earliest examples of an interactive comic as 1995’s Argon Zark!, created by cartoonist Charley Parker. Though primitive, Argon Zark! showed design choices and sensibilities unique to the web medium that were ahead of its time, due in part to Parker’s background in web design giving him a more complete knowledge of web development. However, as McCloud points out, it remained constrained in the regular page layout of a print comic, following the habitual left-to-right-top-to-bottom page layout of print media. Argon Zark!’s biggest innovation, however, was in the use of interactive Flash Player elements it would occasionally pepper its strips with. This would prove to be one of the earliest uses of multimodality as part of the storytelling of a comic—the use of multiple modes of communication in conjunction with one another, rather than separately. In this case, visual, aural and kinetic.

Garrity brings up Jesse Reklaw’s Slow Wave as another key text in the rise of interactive comics, a surrealist comic strip with a simple twist: all the comics were dreams readers had e-mailed Reklaw. What we must focus on here is the idea of interactivity and multimodal presentation. Together, Argon Zark! and Slow Wave show two modes of communication that are uniquely suited to the webcomic: the picture in motion and reader interaction, which together could create a dynamic, reader-driven narrative. Following from McCloud’s earlier example, the CD edition of Maus and CD games of the early '90s also give us a glimpse of another mode of communication that webcomics may take advantage of: multimedia presentation.

It is not out of the realm of possibility that print comics may include supplementary material or reader input; the concept of Slow Wave was done via letters to a newspaper cartoonist. The key here is the immediacy of such interactions. With e-mail or web forums, writers could receive feedback from readers near instantaneously, rather than in however long it might take to deliver mail. Similarly, with multimedia web design, comics could integrate music and even fully interactive segments seamlessly into their narrative. McCloud argues that many of the features that he at the time had envisioned were not possible in the HTML language, but makes a note of the potential for the then-nascent Flash and Java programming languages. This prediction would turn out to be completely correct, as both Flash and later JavaScript would become the cornerstone of Web 2.0, and in turn the foundation for what’s arguably the best realized example of McCloud’s vision for webcomics so far, MS Paint Adventures.

MS Paint Adventures was a website in which writer and artist Andrew Hussie hosted four of their comics, Jailbreak, Bardquest, Problem Sleuth and Homestuck. Prior to this, Hussie hosted all of their work on their personal site before transitioning its forums to the new MS Paint Adventures site. In 2018, MS Paint Adventures was renamed Homestuck.com, and revamped to focus on the last of the four comics, which was both the most popular and longest running at over 8,000 pages, following Hussie’s sale of all MS Paint Adventures properties to publisher VIZ Media. VIZ would take over operation of the site, changing the layout and focusing it primarily on Homestuck, while allowing readers to browse the previous stories. Hussie’s earlier work includes a few traditional comics intended for print publication, as well as other webcomics and comic strips.

By 2008, Hussie was already an accomplished independent writer and artist, and if one looks at their work intended for print, their artistic sensibilities felt almost constrained by the page. Hussie’s art style generally disregarded standard panel composition in favor of letting pictures in the pages flow into one another, having each page show more of a complete picture than a series of smaller images. Hussie had a habit of pushing the boundaries of their figures while keeping everything in the page visually clear, creating dynamic images that flowed into one another as the story’s pace dictated.

Though prolific, Hussie shows a habit of letting their work disappear - the only reason most of their earlier comics can still be read is thanks to Hussie’s fans creating backups and archives hosted independently. Even Homestuck, these days, is best read through a fan-made reader application on the desktop, due to how VIZ has failed to maintain and update the site’s Flash-based architecture, rendering sections entirely unreadable. Regardless of all this, the origin of MS Paint Adventures can be traced back to Hussie’s own forums tied to their earlier webcomics. Hussie themself confirmed this in an interview with Elijah Meeks (2010) for the blog Digital Humanities Specialist, hosted by Stanford University, discussing the design process behind Homestuck.

In the interview, Hussie explains how the website began as a game on their forum, which they later spun off into a larger project. The way it worked was simple, Hussie gave “players”, fellow forum posters, a scenario, and readers would suggest “commands” that Hussie would then draw out and describe, as a sort of mix between a tabletop roleplaying game and computer text-based adventure game. This was not a new concept—roleplaying games such as this one are common in most online forums even to this day. Hussie themself admits to be certain they probably did not come up with the concept, and someone had to have done it before. The difference here is that Hussie would later use these forum games as a storytelling engine for their later work.

The first two “games”, Jailbreak and Bardquest, consisted of Hussie mostly just acting as a sort of Game Master for their forum, drawing out commands as they were input. Both were archived in the MS Paint Adventures site once it launched. Even at this early stage, narratives quickly grow in complexity. Jailbreak was a series of commands in which a character attempts to escape from a jail cell, totaling 134 pages separated by individual commands. Though Bardquest was much shorter, it experimented with branching paths that players could take, reaching 47 pages with several commands per page, allowing the reader to go back after reaching a “Game Over” screen.

Problem Sleuth, Hussie’s third comic, was intended to be more complex than its predecessors. The comic follows three detectives in a parody of the noir genre, and quickly shifts into a mix of fantasy and absurdist comedy. The story is presented in the style of a computer adventure game, to the extent of characters having inventories separate from one another to use in commands. Like the previous two games, readers would suggest commands which Hussie would then pick from and draw. Readership grew, giving Hussie more options to choose from before moving the story forward. Unlike the previous games, Hussie had allegedly planned story elements in advance, rather than writing off the cuff, leaning more into the format of running a collective game in which readers played the role of all the characters at once.

Hussie describes the relationship to their readers as a sort of cat and mouse game, where a lot of the comedy came from a narrative of tug of war between established plans for the story and commands that players would input. Hussie reiterates this in another interview with Michael Cavna (2018) for The Washington Post, elaborating on how a simple scenario in Problem Sleuth might move into more complex and fantastical story developments, bringing up time travel, theoretical physics and recursive references to video game logic. This sense of gratuitous escalation of complexity would later become a staple of the site as a whole, along with Hussie’s writing.

Problem Sleuth would also introduce a new element to the presentation, in the form of animation (figure 03). Occasionally, and more commonly as it went on, panels are presented as animated .gif files of varying complexity. Some of these only do so for backgrounds or slight movement, while other panels would use these animations to display more complex actions, such as beats in a fight scene or objects moving within the frame. The overall intent is to make the comic move at the pace of an old computer video game, where actions only progress following player input, and animations loop if left undisturbed - giving the visual effect of time being frozen in motion. Once again - much like a temporal map made up of snapshots of movement.

By this point, Problem Sleuth used all of the elements of its predecessors to tell a complete story, using the visual style of Bardquest and Jailbreak combined with limited animation and constant shifts in art style while remaining visually consistent, shifting as the story or specific jokes demanded. Problem Sleuth would continue for 1,600 pages and 22 chapters, written through reader input from start to finish. What Problem Sleuth had managed to accomplish was taking the collaborative game-writing formula of its predecessors and applying it to a rough narrative plan, while using the affordances of web media to enhance the reading experience, drawing readers in. Combined with Hussie’s own eclectic artistic sensibilities, these elements give Problem Sleuth a unique personality and style that set it apart from its contemporaries or even successors. Hussie would take the lessons in design from Problem Sleuth and further refine them in its follow-up, Homestuck, which would take the formula established by it and add in everything from fully animated chapters, interactive game segments, and 20 music albums, with greater community influence and involvement; yet, paradoxically, written without direct reader participation.

Homestuck is the last comic produced for MS Paint Adventures, running intermittently from April 13th, 2008, through April 13th, 2016. Like Problem Sleuth before it, Homestuck began as an interactive story, having readers suggest commands for characters to follow in the same way as its predecessors. Like Problem Sleuth, several elements of Homestuck’s story were planned in advance. After the first year and four chapters of constant publication, Hussie would cease taking commands directly from readers, but kept the command format for individual pages, as it had become a stylistic trademark of the site. That is not to say that the comic had no further input from readers, as readers in the MS Paint Adventures forum named most characters, and the comic would gain a great deal of social media fame, which Hussie also reacted to directly within the story.

Homestuck increased the complexity of its story while adding new formats of presentation as it went on. Where Problem Sleuth had experimented with the use of animated panels, Homestuck would feature them as well, as well as fully animated Flash videos, complete with music. The music for the comic was produced by other forum members and friends of Hussie’s, such as now-famous video game developer and music composer Toby Fox, of Undertale fame, who provided a sizable amount of the music for the entire run of the comic, along with contributions in art and writing. Many of the style sensibilities that made Undertale an indie darling are visible in Homestuck, making it an interesting companion piece.

Also following in the footsteps of its predecessor, the plot of Homestuck begins with a simple setup that grows into an infamous degree of self-referential complexity and narrative density. The initial premise of four children playing an online video game that alters reality around them quickly grows into a coming-of-age epic touching on the themes of survival, predestination, nihilism, time travel, and obscure movie references; chapters in the story (titled “Acts”) grow exponentially longer, giving the comic a degree of infamy due to its sheer length. To this day, online discussions on the comic remark on its gargantuan length first, and content second.

The comic doubles down on the adventure game format by having video game abstractions such as inventory management being real narrative devices used to advance the plot on several occasions, with a running gag of characters spending untold amounts of time learning to use their inventory only to rarely bring it up again. User interface elements such as menu systems and standard icons accompany these segments, making the comic look much closer to a video game in visual design than its predecessor. Part of this has to do with the readers playing along as they read; though new readers tend to complain about the slow pace of early chapters caused by readers playing around with the in-story game mechanics for dozens of pages at a time, this in a way contributes to the framing of the story as a world running on video-game logic, as players will often find themselves fiddling with game mechanics and inventory systems for hours at a time when first learning a game.

The biggest addition to the page design is the dialogue’s presentation in the story. Because characters begin the story talking to each other through a chat client exclusively, the comic portrays dialogue through “pesterlogs” - chat logs in which characters are identified by the color of their text, abbreviated handle, and distinctive typing styles, emulating the appearance of chat clients such as AIM [AOL Instant Messenger] or IRC [Internet Relay Chat]. These chat logs would become one of the standard design features of the comic, to the point that its spinoffs would continue to use the design despite it not having the in-story justification of characters speaking through instant messages. This form of dialogue presentation is not done just for the sake of aesthetics, as it is used as a way to communicate each characters’ personalities to the audience, even before they are properly introduced. Character typing quirks, such as their use of punctuation, spelling and grammar and other stylistic choices, are used to give the audience a better idea of the characters’ voices and personalities before and after they’re formally introduced or even named.

This helps humanize the cast, as the typing styles reflect the way people talk over the Internet. Hussie uses these small elements of visual design in order to both inform characterization and advance the narrative, as well as endear the characters to the readers quickly and effectively by tapping into the intended audience’s experiences in online environments. This particular design choice shows an innate understanding of online social dynamics of the time, and makes Homestuck a time capsule of pre-social media online etiquette (and/or lack thereof). Later on, this same writing quirk is used as a form of worldbuilding for different alien societies in the universe of the comic.

As stated earlier, animation is also present throughout the story to a much greater degree than in Problem Sleuth. Most panels are composed of .gif files showing looping animations, in the same style as its predecessor, whereas still panels are the exception. Flash animated sequences were initially reserved for important events, like the end of an act, but become much more common later on. Hussie admits in both aforementioned interviews that they were the most difficult part of the entire endeavor. Besides tweening-based animation, full digital animation and even live action claymation are used in places during the story. Animation styles varied, earlier taking the appearance of slideshows and limited sprite animation, shifting between the comic’s usual artstyle and more detailed styles as the action progressed, using motion tweening rather than animating character movement by hand. Later on, fans would contribute art for these animations, and the last chapter of the story, Act 7, was entirely animated by fans of the comic.

Over time, Hussie would experiment with interactive animations and split paths merging back into the main narrative. Early on, some Flash pages would show small game-like animations that readers could interact with, such as the main characters having combat encounters in the style of a role playing game, giving the reader options that would play out different animations before moving on to the next panel. Hussie would later integrate completely interactive segments where readers would take on the role of one or more characters, walking around talking to other characters and solving puzzles, adopting a visual style reminiscent of multiple 16-bit video games of the 1990s, which make up a good amount of the comic’s pop cultural reference pool.

Though the readers take on the role of the characters in many places, a running gag carried over from Problem Sleuth involves the readers themselves being a character in the story, as well as Hussie, who exists in the periphery of the narrative, literally writing and drawing the comic from within its world. Meta-narrative jokes such as this would make up a majority of the humor in Homestuck, adding to its already daunting narrative complexity. By the end of the story, most of the final chapters are dedicated to closing complex time loops and relationships of causality between them, with the actual end of the story being explained a few hundred pages before the story would conclude. Just like Problem Sleuth before it, Homestuck would use any chance it got to make the narrative more convoluted, up to a point where the main character travels through the narrative of the comic itself to affect continuity retroactively, in doing so doubling the size of the still-living cast, almost as an acknowledgement of the comic’s infamous amount of characters. With all that, the comic would last over 8,000 pages, 15,000 panels and, by some counts, four hours of animation by the time it was finished, making it one of the longest works of fiction in the English language by word count alone. This level of density became its defining feature to outsiders, as well as a point of pride for its readers.

In a short video essay for the PBS’s Idea Channel hosted on YouTube, Mike Rugnetta (2012) proposes a comparison between Homestuck and James Joyce’s Ulysses, along with other works with a similar reputation as impenetrably dense, arguing that the overwhelming complexity and self-referential textuality of both works is what draws readers in, while also providing a sense of effort justification to those who stick with it. He was not alone in making said comparison, as the aforementioned Washington Post interview also opens with that analogy, and many others would use Ulysses as a point of comparison to explain the appeal and difficulty of the work. Rugnetta also makes a passing mention of the comic’s popularity, referencing the online joke about Homestuck cosplayers populating conventions at the comic’s peak in readership. The comic gained a reputation for its sizable fanbase being near inescapable in social media in the early 2010s.

With popularity comes fandom, and Homestuck fans proved particularly creative. Many fan creators would later go on to join the art and music teams of the comics, and work on later spinoffs. At the same time, Hussie alludes in this interview to the fact that increased fame meant increased scrutiny of their work, as nearly every update and plot development would create controversy among the readership, to Hussie’s irritation.

The comic would end in 2016, but the Homestuck brand would continue and outlive MS Paint Adventures entirely. In 2012, Hussie launched a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign for a Homestuck adventure game. The campaign was successful, with the first episode of the game titled Hiveswap: Act 1 releasing in 2017, and its second episode, Act 2, releasing in late 2020. Between that, visual novel spin-offs Hiveswap: Friendship Simulator and its sequel Pesterquest would be released between episodes. A duology of web novels stylized after fanfiction dubbed The Homestuck Epilogues was released on April 13th, 2019, on the 10th anniversary of Homestuck, leading to a non-canonical sequel, which has been put on hold due to negative fan response as of the time of writing.

In 2020, Flash Player was phased out due to obsolescence; as such, most of the site’s Flash-based assets were converted to HTML5 elements or uploaded to YouTube as videos, losing quality in the process. As of the time of writing, the original Flash versions of the animations are only available through fan-archived, non-official collections.

MS Paint Adventures’ larger impact is in codifying the interactive webcomic format, as other comics would follow its example as early as the release of Problem Sleuth. Jonathan Wojcik’s ongoing horror comic Awful Hospital uses nearly the same format as MS Paint Adventures, allowing readers to input commands and using embedded audio along with JavaScript and HTML5-enabled animation to much of the same effect. Similarly, the website MS Paint Fan Adventures allows users to create, host and read comics in the style of MS Paint Adventures, along with providing its own suggestion box and a user interface designed to be as close to MS Paint Adventures’ as possible. WebToon, a Korean platform currently dominating the webcomic environment, also hosts multiple comics that integrate animation and even music into their narrative, such as Room of Swords or Hooky. Despite all this, however, no other comics since the end of Homestuck have managed to replicate its seamless blend of multimedia styles presentation, partially due to the workload involved, difficulties of development in the current online ecosystem, and the domination of social media-compatible comics. Despite Homestuck’s overwhelming success, in this day and age it remains an artifact of the past decade, with the webcomics landscape having moved on to greener pastures.

Yet, the sheer achievement of MS Paint Adventures as an experiment in format and presentation deserves more recognition for proving its concept can be done. 22 years ago, Scott McCloud only dreamed of a future where comics would be unbound by space of the page and the panel and the silence of ink on paper; where a comic could present itself in any way and shape it wanted, and stretch beyond the physical space of a bookshelf. McCloud wondered about a far future where Virtual Reality would let readers become part of a story, and a less-distant future where readers could interact with and explore the worlds of comics. At the time, he himself admitted it was a pipe dream, but called creators to take him up on his vision. MS Paint Adventures proved to be lightning in a bottle – the right combination of an author with the creative vision to push the boundaries of their own medium, a creative community that supported this vision, and an online environment that allowed readers to flock to them and their co-creators’ worlds. Perhaps unintentionally, Hussie and their team of artists, musicians, fans and forum buddies created a complete, uncompromised rendition of McCloud’s concept of the Infinite Canvas; a comic that managed to use all of the tools web media has to offer in order to tell nauseatingly long, complex and ambitious stories, so massive they had to be written by entire communities of readers, writers and creators, with a creative lead at the helm who acts less like an author and more like a referee.

The lesson to be learned from MS Paint Adventures is that the sort of online community building unique to web media can allow creators to transcend the boundaries of their artforms, and it is my belief that it will again in the future. This will require them to share in the creative process with both their fellow writers and their audience, and to think outside the box when using the tools and methods afforded to them. The result will no doubt be messy, confusing, convoluted, controversial and immediately dated, but it will be a unique snapshot of the environment that created it and the people it reached. It will be something uniquely digital, rather than imitating the analogue, an evolution of the form adapting to take advantage of the new affordances at its disposal; and consequently, whatever the next artist to see this concept all the way through ends up creating will be something that could only have come to exist in the digital age.

A list of some of the references discussed follows:

- Cavna, M. (2018) ‘'Homestuck' creator explains how his webcomic became a phenomenon.’. The Washington Post, 30 October [Online] Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2018/10/29/homestuck-creator-explains-how-his-webcomic-became-phenomenon/ (Accessed 29 April 2021)

- Garrity, S. 2011. “The History of Webcomics”. The Comics Journal, 15 July. Available at https://www.tcj.com/the-history-of-webcomics/ (Accessed 20 April 2021)

- Holkins, J. and Krahulik, M. 1998-Ongoing. Penny Arcade. Available at https://www.penny-arcade.com/ (Accessed 30 April 2021). https://www.penny-arcade.com/

- Hussie, A. 2008–2009. Problem Sleuth. Available at https://www.homestuck.com/problem-sleuth (Accessed 30 April 2021). https://www.homestuck.com/

- Hussie, A. 2009–2016. Homestuck. Available at https://www.homestuck.com/. (Accessed 30 April 2021). https://www.homestuck.com/

- Kleefeld, S., 2020. Webcomics, London, Bloomsbury

- McCloud, S. (2000) Reinventing Comics: The Evolution of an Art Form, New York, Harper Collins

- Meeks, E. (2010) ‘Interview with Andrew Hussie, Creator of Homestuck’, Digital Humanities Specialist, 3 December [Blog]. Available at https://dhs.stanford.edu/social-media-literacy/interview-with-andrew-hussie-creator-of-homestuck/ (Accessed 29 April 2021)

- Misemer L., (2019) “A Historical Approach to Webcomics: Digital Authorship in the Early 2000s”, The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 9 (1). P.10. Available at https://www.comicsgrid.com/article/id/3588/ (Accessed 20 April 2021)

- Parker, C. 1995-Ongoing. Argon Zark!. Available at https://www.zark.com/ (Accessed 30 April 2021) https://www.zark.com/

- Rugnetta, M. Is Homestuck the Ulysses of the Internet? (2012) Youtube Video, added by PBS Idea Channel [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLK7RI_HW-E (Accessed 29 April 2021)