Last July, a big retrospective exhibition for Zoran Janjetov under the title Antibody was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina in his native city of Novi Sad, in Serbia. Considering that Novi Sad is not a big city, it was quite a response when more than 1,000 people rushed to visit the exhibition. The focus of the exhibition, which included more than 400 pieces, was not solely on Janjetov's well-known collaboration with Alejandro Jodorowsky (Before the Incal, The Technopriests and others). It encompassed many other aspects of Janjetov's talent, including graphic design, illustrations, sketches, and his comics that are less or not known in France, Europe, and the USA. Zoran is a kind of cult figure in the countries that emerged after the bloody collapse of Yugoslavia. However, his cult status there is partly different from that in the rest of the world. In his home part of the Planet, he is known not only as a great visual artist but also as a storyteller. The exhibition catalog included several textual contributions and a huge bibliography. Jodorowsky contributed a loving letter to his long-lasting collaborator. My essay was somewhat different in approach than that of the other participants. It was a critical insider view, because I share some 35 years of friendship with Zoran. What follows is a new English-language version of that text.

* * *

I first wrote about Janjetov 34 years ago. That’s when I fell for his art at its freest. Then I fell for it again, 13 years ago. I am trying to link it all to the present moment. I wondered what the best title of the current essay would be. I realized that it had to be the title of the first one, since nothing rivals its metaphoric depiction of Zoran Janjetov’s creative being.

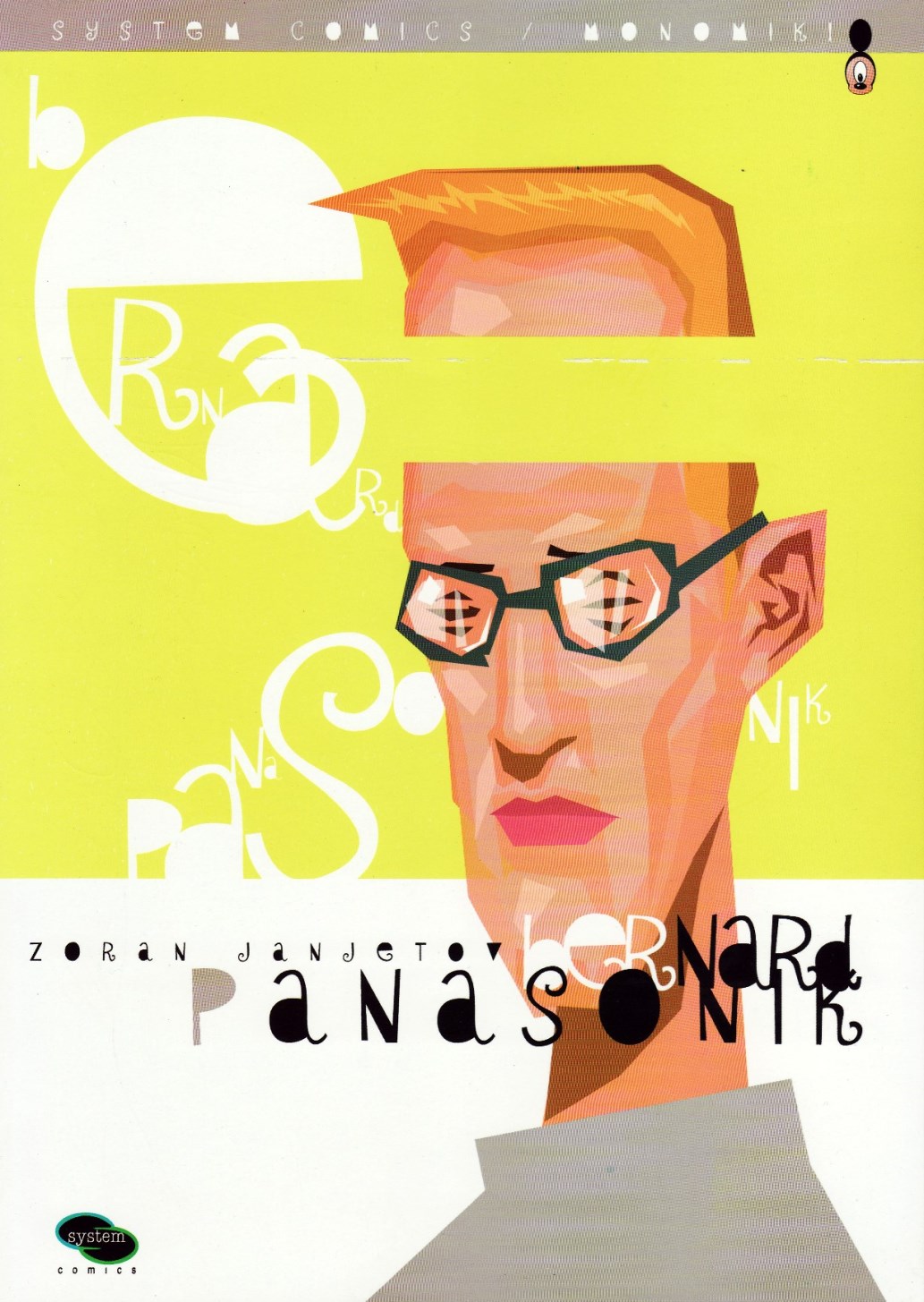

Since the very beginning, the visual world of Janjetov’s art has created unbreakable connections between comics, illustration, and design. The coloring of his Bernard Panasonik covers is the unforgettable gatekeeper that set standards so high that no one has tried to meet them, let alone mimic them. Those and other illustrations appearing as part of Janjetov's cover art design had nothing in common with the attempts at “fine arts” realism typically featured in some comics, more often than not ending up as a sort of kitsch - or, at least, awkwardness. Janjetov’s illustrations were characterized by a comics idiom incorporating streaks of cutting edge design (typography, playing with “intruding” graphic elements, composition, and contextualization within the cover art design). Their flabbergasting beauty and poise endured, remembered and invoked throughout the decades to come: cover art for the magazines YU strip and Ritam, as well as the albums Bernard Panasonik (1990) and The Coloring Book by Professor Ćumislav (1992). At the Third Yugoslav Comics Festival (Salon Jugoslovenskog Stripa) in Vinkovci in 1986, Janjetov was the recipient of an award for numerous illustrations constitutive of his comic art poetics.

Janjetov’s impressive international career in France and beyond is not the focus of this short essay. Instead, it looks at a more modest or, if you will, more ambitious goal - drafting that what I find to be the essential gift of this wondrous author.

On one occasion, I claimed that many significant domestic authors emerged from the Moebius overcoat. This statement acquires a dramatic edge in the case of Zoran Janjetov’s art. The foregrounded obviousness of his artistic role model initially caused confusion and a questioning of the merits and authenticity of those comics Janjetov created before the period of his international acclaim. Paradoxically enough, when he succeeded Moebius and started his long-lasting collaboration with Alejandro Jodorowsky, those objections ceased. At the time when he was working on Bernard Panasonik, Janjetov consciously opted for a Borgesian position of a “parasitic author.” Knowing how difficult it is to be a good reader, he started deploying his talent in the service of enriching the reader-creator sensibility. The departure point within this endeavor was to establish the kind of relationship with Moebius’s oeuvre that would parallel the relationship between a book and a footnote referring to it. Then, the footnote would be transfigured into a book. Janjetov’s work epitomizes reader passion - the desire to sustain the world of Moebius, to contribute personally to its expansion and enduring presence.

However, the Tower of Babel's comics library is enigmatic. The game of mirroring and betrayal is unpredictable. Even Borges himself contends: “In the vast Library there are no two identical books.” Moebius’s early works (Arzach, The Airtight Garage, Is Man Good? etc.) are the embodiments of irony in comic art. In Moebius, ironic distance enables divergence from the conventional, common meaning. In that sense, Moebius parodies genre conventions (science fiction, the western idiom), the structure of the psychology of characters, the anatomy of the figures, and—if it’s even possible—perspective and spatial relations.

How could Zoran Janjetov’s “parody” as a variant of Moebius’s “parody” obtain autonomy? How is it possible to parody Moebius’s work to start with, when it is itself saturated with irony? It is possible by virtue of that what Moebius’s irony of the “Screaming Metal years” lacks: childlike warmth and naiveté. Janjetov thoroughly investigated Moebius’s line art technique and his approach to work. He adopted the major portion of Moebius’s iconography. Generally, however, there is a decisive difference between Moebius’s and Janjetov’s poetic structure. Janjetov has applied the infantile subversion of coldness to Moebius’s limitless imagination and irony. In his profoundly personal interventions, Janjetov made the Moebiusesque vernacular surrender to Winnie-the-Pooh via A. A. Milne and the illustrator E. H. Shepard; the worlds of Walt Disney and the creative geniuses in the service of his production, notably Floyd Gottfredson; Chlorophylle (est. 1954) from the genius of Raymond Macherot; the masterpiece Spirou & Fantasio by André Franquin; and of course Hergé's Tintin.

Let us go back to Janjetov’s reader (and viewer) passion in order to better understand his infantile subversion strategy. As a viewer, he found himself in a schism between the media and the genre. He is an admirer of the genre-based approach in movies. By contrast, in comics, he gravitates toward “something else” - metagenre creation. The infantile subversion strategy is his defense against the imposed siding, allegiances, and choices between the polarities: “genre-based” or “artistic” approaches to creation. Instead, Janjetov chooses an intimate approach to “the stupidest and silliest things,” thereby infusing warmth into and misusing the references pertaining to genre conventions. In that sense, he continues Moebius’s endeavor by referencing not only Moebius, but rather the whole Tower of Babel comics library of mass culture.

The Bernard Panasonik series (1982-1994) was not intended to end. It stood for everything that was unknown in terms of the conceptualization of what comics and comic series could be. In addition to Panasonik, Janjetov gifted us with a series of short comic stories and three outstanding series: Kosta the Mouse (1979–1988); From the Notes of Professor Ćumislav (1984–1992); and Mikke Musse/Mike Muzzak/Monomiki (1986–1990) - as well as unforgettable graphic and textual escapades in the publications STAV and Glas Omladine in the late '80s, including the phantom installments of the “novel” The Missing Avenue by Herbert Kraus. Many years later, Janjetov continued, in a certain sense, this world of infantile bravura by creating on a daily basis sketches and the most casual illustrations using all sorts of techniques ranging from ink via pen to colored pencils. Only some of them have been collected into this tiny, small-run print book, while his incredible collection of drawings continually grows like a magic beanstalk.

Janjetov’s infantile subversion of coldness was intentionally chosen to occupy the closing chapter of my 1988 book Thomas Mann or Philip K. Dick: Essays on Comics. At the very end of the book, I gave voice to an excerpt from Janjetov’s unpublished comic Zoran Zoran: “Dear diary, this day started with excitement and eventfulness. I swung by Steve’s for some interesting cakes. Then, I called at Mrs. Smith’s for some petite madeleine. I ate like a horse, and now I’m feeling terribly sleepy. We, warriors, are leading an utterly hard life, and have to take it easy now and then. The forces of deep water and dark woods help me with the most wonderful play, and I think that all shall be well. At the moment, I’m on my way to Maks for some bean pie. May this be the period of truce and may god grant me peace and quiet. Life is a kangaroo, and who knows where it will bounce off tomorrow.” There really is no better way to end a book which wrote me as well, given that I was going to live in Amsterdam during the following three decades.

Each period, each epoch bears some outstanding artists. In the realm of “noncommercial” comics—whatever the hell that means and however it leaks into the wide delta of quite-distinct things—such extraordinarily prominent individuals appear more rarely, which only makes them more valuable. The screenplay power of a René Goscinny is that what was lacking in the comics in the former Yugoslavia - or, in accordance with the current “politically correct” terminology, the Region. One should note the stunning paradox that brilliant storytellers eventually emerged, albeit where they were least expected. A shining point is Aleksandar Zograf, who originally appeared as an underground artist and later relocated to the pages of the weekly magazine VREME. The other is an apparently non-narrative comic—don’t hold your breath now—Bernard Panasonik. In this masterpiece, Janjetov proved to be an exceptional storyteller. A stray, naïve passerby through the wilderness of attempts to understand narratology could wonder where its storytelling is in the first place. It hides underneath bizarre situations and characters, and emanates from masterfully composed dialogs and, generally, a superb idiom. If only the “peaks” were cut off from a Bernard Panasonik, there would be a spectacular narrative skill, similar to seemingly bizarre TV series such as Twin Peaks, The X-Files or Lost: marvelous characterization; astonishing dialogs; enduring suspense between the somber and the ironic; and the knots where a joke is transfigured into meditation.

No, this is not a speculation along the lines of “he could have been a storyteller if he had continued writing his comics.” Zoran Janjetov is a born storyteller. Bernard Panasonik is a masterpiece. It is one instance, albeit the most fascinating one, of the crystallization of his storytelling gift preserved in the two editions of the book. It's Janjetov’s Airtight Garage, yet in storytelling terms more vigorous than the “original.” Bernard Panasonik is a more warmly dreamed story:

-Based on the book "The Missing Avenue" by Herbert Kraus.

-I'll read you a poem I wrote when I was fifty-four: "Oh, love, you strange bird, my love is still wayward, I love fishes and small kids, cookies, muffins, and pretzels."

-I think that metaphysical imagery here nicely contradicts the underlying metaphor. Great poem!

-Here I am, sitting in a stone room with two complete jerks, and I still feel OK. Maybe I'm losing my mind.

-Now let's see who, apart from the author and the main characters, turned out to be a sucker in the previous episode:

-Sucker

-Sucker

-Sucker

-Sucker

-While we were busy arguing like fools, they left. They didn't even have to run.

-You're not real. You're an apparition. You're more than apparition. You're a nightmare, Cauchemar. You are an apparition. You are an apparition. Come on, tell me you're not real. Tell me.

-Listen, Shesha, there's nothing there to tell. You're just saying this because of my tail, right? Stupid tail, no one believes in me because of my stupid tail. And you still believe in puppies and kittens, don't you? It's not fair.

This is one of the numerous astounding excerpts from Bernard Panasonik. A perfect rhythm of ridiculous sentences that tear one between surrealism and Daniil Kharms.

French comic culture has no idea what a comics storyteller genius it has lost, having never even found it. I tried more than once not to forgive Zoran Janjetov for not fighting to make the translation of Bernard Panasonik available on the French market. Needless to say, it would have needed to be expertly executed, for sure, as necessitated when it comes to such a piece of art. Janjetov, however, does not fight to prove his worth. That personality trait is missing, it slips through one's fingers. He is a child prodigy who lives his life in a fragmentary idleness, the valley of happiness. One can only envy him. Zoran–Janja is authentic, self-conscious, an infantile genius. His life is happier being lived this way.

There is an incredible explanation of meaning in Karel Čapek’s novel Krakatit: “You will not reach the highest, you will not release everything [...] You will not save the world. Nor will you destroy it. Many things will remain encapsulated in you like a spark in a stone. That’s the way it should be.”

Once I said that my highest philosophical objective was acquiring the unconditioned joviality of a puppy. A puppy can perceive the meaning of the universe better than any pondering in my essays and analyses. Perhaps Sir Jeangetoff (the way the French funnily mispronounce his name) would agree with this?