From The Comics Journal #198 August 1997

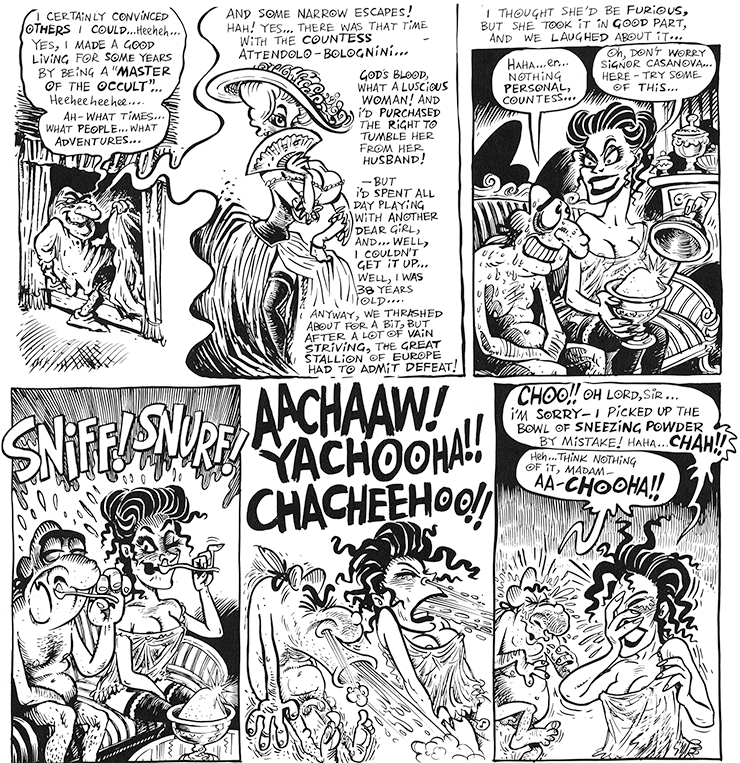

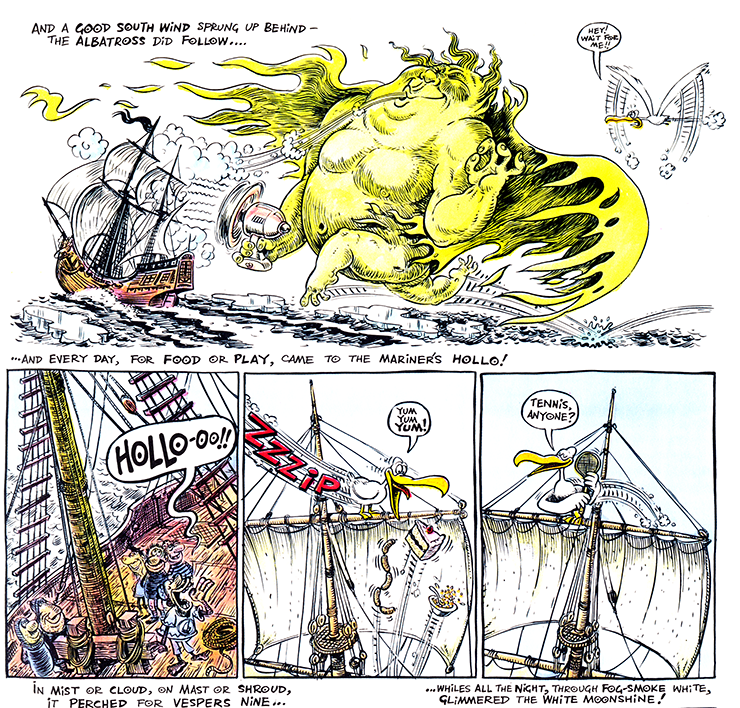

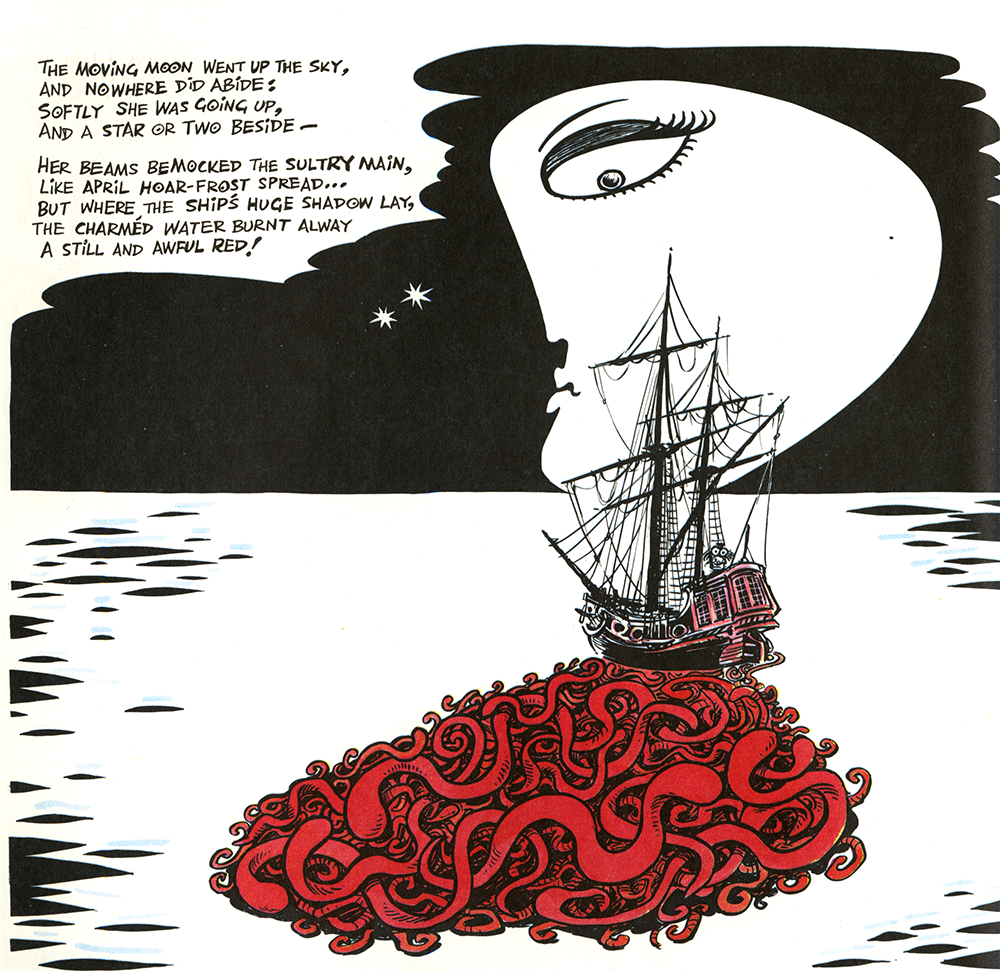

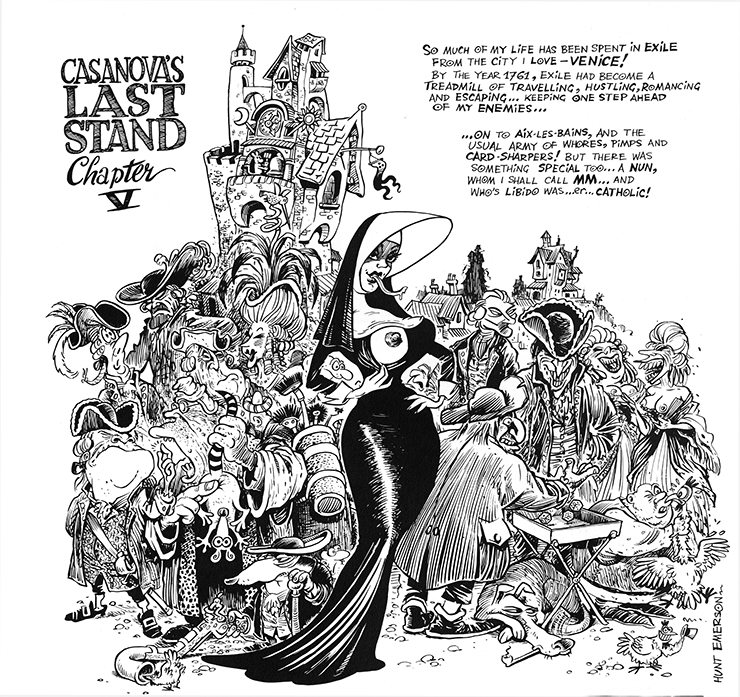

Hunt Emerson stands alone. With Bryan Talbot and Steve Bell ( … If), he is the only survivor from the brief heyday of the British underground press. Unlike his contemporaries, he still works there. After cartooning for regional undergrounds and a period in the fertile environment of the Birmingham Arts Lab In the ’70s, he found his true home in 1978 at Knockabout, the customs-battered keeper of Britain’s underground flame. His books for them have included 1983’s career-spanning The Big Book of Everything, the character-based Calculus Cat and Jazz Funnies, literary adaptations like Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Casanova’s Last Stand. He also draws Firkin the Cat, written by Tym Manley, for porn magazine Fiesta. His cartooning, influenced at first by American underground comics, is distinctively British, a sort of ribald Baxendale. In France, he is rated alongside Crumb and Shelton.

It’s a career which is hard to put into context because it barely has one. Due to its nature, his work has always existed on the margins of British comics. The popularity of the likes of Alan Moore hasn’t helped him at all. Still, the quality of his work has steadily grown. The only thing that hasn’t improved, to his frustration, is sales. His comics just don’t fit. This interview took place over two sessions, the first In Emerson’s apartment in Birmingham, England, in the summer of 1994, the second in London a year later. The last section, “Aftermath,” is drawn entirely from the second session. Both were bad times for Emerson, inconvenient in various ways, which may account for the occasionally strained nature of what follows. The questions also took turns which the cartoonist, rigorously funny and free from intellectual analysis in his work, didn’t always find easy to accommodate. But to his credit, he left the transcript virtually untouched. What follows is a sometimes raw, sometimes tight-lipped (but always honest) conversation with a major talent. — Nick Hasted

NICK HASTED: Let’s start with some biographical stuff. When and where were you born?

HUNT EMERSON: I was born in Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1952. Newcastle’s in the Northeastern England. It was originally a big industrial area, ship-building and coal mining. And that’s no longer the case.

Is there anything that stands out from your childhood? Anything that was unusual about it?

Unusual? [Pauses.] Only that I could draw. [Laughs.] It was always with me. No, I had a very normal childhood, I think. My dad used to work for the weather service, he was a radio operator and he used to work on weather ships and go out into the Atlantic on tours of duty, which meant he was away quite a lot of the time. He was away four or five weeks, and then home for a week. So, I don’t think I built a really strong relationship with him when I was younger. And then of course in my teenage years, I argued with him all the time. And my mum was busy with my younger brothers as well. It was quite a normal childhood, looking back on it. And also looking back on it, it was as abnormal as anyone else’s, I’m sure.

Is there anything from your childhood, or from your teenage years, that shows up in your work now?

No, I don’t think so. l wasn’t really interested in comics very much. I was always interested in drawing, and I used to love TV programs with artists on them, like Sketch Club: With Adrian Hill. Adrian Hill was an artist who wore an artist’s smock and a flamboyant cravat and had long sensitive hair and long sensitive fingers, and he used to do a thing on the BBC where he’d show you how to draw a landscape, or how to paint a waterlily. He’d work it up from start to finish, all in black and white. That sort of thing used to fascinate me. I loved watching people draw. I can probably still draw some of the things I learned back then. But I was never that much bothered by comics. We weren’t allowed to read the cheaper comics, The Beano and The Dandy and Knockout. They were frowned on in our house. We had to get comics like Look and Learn and Eagle, educational stuff. But I didn’t used to read much of them, I used to look at the pictures, and that was it.

Were most of the things that stimulated you visual?

[Pauses.] l don’t know. When rock ’n’ roll music came along, and the Beatles started, that was it, the end of everything. Life became one-directional. But up until then, it was just a childhood. I was always very into war, I know that: soldiers and war. I used to go out to school in the mornings — especially winter mornings when it was really foggy, and I couldn’t see the school at the end of the hill because it was so foggy — and I used to have these fervent imaginings that war had broken out and school had been blown up. [Laughter.] It never worked.

What exactly was the impact that rock ’n’ roll and the Beatles had on you?

It was just what life was all about. I started playing the guitar when I was 11, with my brother, who was a year younger than I. And by about 12 or 13, we were doing gigs, we had a group. That lasted until I left home to go to art college when I was 19.

It seems like quite a rapid reaction from you because you must been 10 when “Love Me Do” came out. Did you feel a need to react to the Beatles as soon as you saw them? Were you that excited?

Yeah, I suppose so. It’s not something I ever thought about at the time. It was just what we did. I was never very interested in football or any of the other things that the lads around were doing. We were musical, me and my brother. My mum was musical, and she had sung when she was younger; my dad played a little bit of piano, much to our surprise. But they didn’t encourage us in this.

But they didn’t discourage you?

Yeah, they did. Very actively! When my dad was at home, we weren’t supposed to be in a pop group, so we had to do everything in secret. But while he was away, my mother used to let us get away with it. It meant that we always had to borrow our equipment from other people and everything we had was ropey. That made me compensate by doing what I could with what we had, so I was interested in arranging the songs and learning the songs rather than getting better as a guitar player.

Had you seen anything like the Beatles before? Did they really stand out?

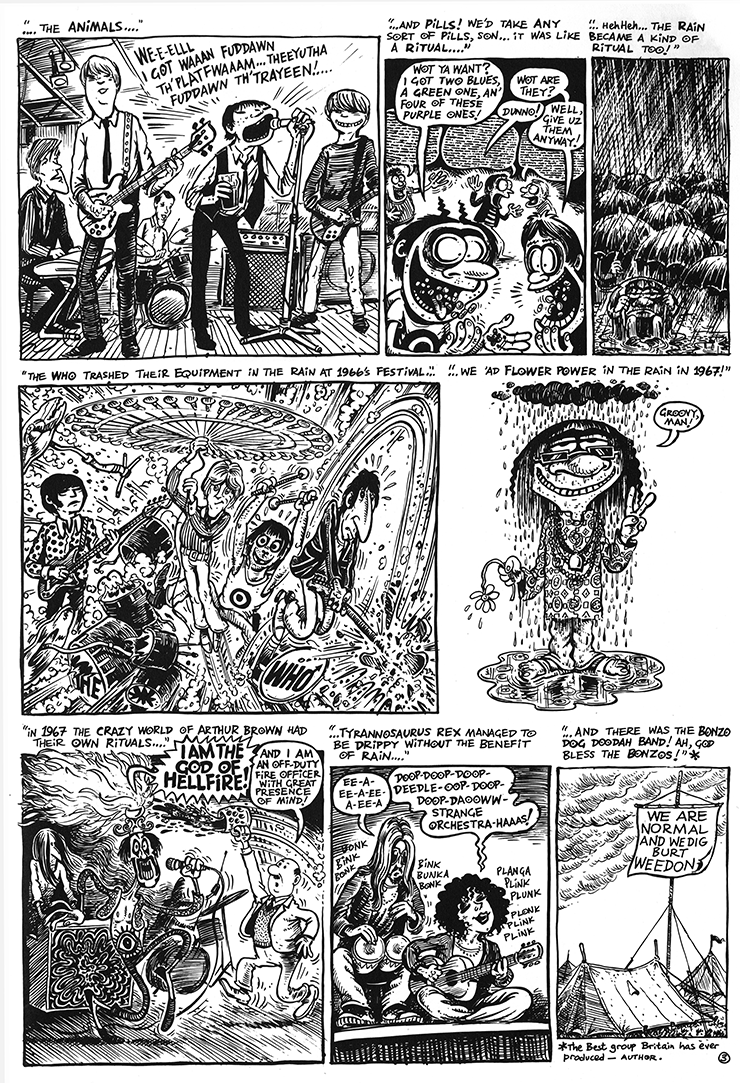

Yeah. It was all completely new. It’s nothing unusual. It was the same for everybody. It’s been said many times how everything suddenly crystallized. And the Animals were a big thing as well, coming from Newcastle. When “House of the Rising Sun” was #1, I remember we were all pleased and proud and surprised that something from Newcastle was Top of the Pops because Newcastle was a backwater — or at least, it was for me. These were schoolboy enthusiasms. Everybody was into it: the Beatles, the Stones, the Animals, Kinks, the Who. Me and my brother took it further. Bur people were forming groups all over the place. That was an important period for us. I wanted to be a rock star then. I was always able to draw, and that was what I was best at in school. But it never really occurred to me to do anything with it because my mum and dad disapproved — my dad in particular, who wanted me to be an engineer or something useful. He had no time for this art business, it was considered an utter waste of time. All through my school years, I wanted to be an artist or a singer. I didn’t really think about it, I had no idea what that meant. But that’s what I used to tell everybody. The drawings were just what I did. I managed to rearrange the lessons I was having at school —officially —so that I had five free lessons a week, which I filled in with art. So, I was doing tons of art all the time, by myself in the art room, not with the rest of the class. They were off doing biology.

Did you enjoy being in a band more?

Yes. I liked organizing, and I liked arranging the music. I was always very busy. Being in a band is a good way of avoiding teenage scenes when you’re kind of shy and unsure of yourself. I never learned to dance, and I never learned to chat up girls because I was always on stage or bustling around trying to fix amplifiers. The rest of the band just used to let me get on with it. I never made any money from it because any money went for guitar strings and microphones. But I was totally wrapped up in it. I was in two bands. The first one was called Size Five, and that was great fun. It was quite tight, and we played lots of pop hits and rhythm and blues and Who songs and Kings songs and Tamla Motown. We did lots of gigs at youth clubs and places like that. I was only 16 when that band finished. The next band was dreadful. We never really had a name, but it was in the British Blues Boom, and we were followers of John Mayall and Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, then Cream and Jimi Hendrix. We had two lead guitarists, and I was the singer. I’d go up and sing a few verses, then stand aside while the guitarists fought it out. It was awful, booming noise.

But did these groups stimulate you in ways other than making you play the guitar? It seems to me that Britain was different before the Beatles that it was from the instant they arrived.

It was a big freedom. It was a new culture that belonged to us. I was reading Marianne Faithfull’s autobiography recently and that brought it through to me again. Poor woman, she had a terrible life — largely self-inflicted, but at the same time, the book rings very true. I recognize the points of view and the attitudes. Had I been a few years older, I’m sure I’d have gone in the same direction as her because they were doing it for the first time. It wasn’t as though she had any good examples to base her life on. Who was to say what people in this position of power were to do? They were doing what they thought should be done, but they were just kids, and kids don’t really think about things too much; they just get stuck in. It wasn’t a case of dressing like hippies for them. They were hippies.

How do you think being a teenager in the ’60s affected you?

I was swept up in the whole mythology. Believed it all, the hippie stuff and everything else. I was a beatnik in Edinburgh when I was about 14 when we were first getting an inkling of what was going on in San Francisco at the time. I was dossing around Edinburgh — I mean, I wasn’t dossing at all, I used to stay with an old auntie, but I used to go and hang around with these beatniks on Princes Street.

How could you be a 14-year-old beatnik?

Oh, just hang around in the park and tell everybody that you were a beatnik. [Laughs.]

But by the time you really got into your teens, had the shine gone off it? Were you just a bit too young?

Yeah. By the time you got into the ’70s, it had become very sordid.

How else did you react as a teenager to this stimulation around you?

Becoming an art student was one thing. I was reading about this new creative freedom and community that was going on, and I was trying to be part of that, without really knowing what I was aiming at.

Did you think of your drawing as a way of responding to what was going on around you?

Not really. I was just reacting from day to day, trying to avoid having to do the sort of job that my father wanted me to do. There was this thing at the time about personal freedom, and really what it meant was doing whatever you wanted.

Was that as far as you got at the time? You knew you wanted to do what you wanted to do, but you didn't know what it was?

I don’t even think I knew that. [Laughs.]

Who were you reading?

Oh God, Tolkien. I didn’t really start reading a lot of good stuff until I left home. I started reading Tolkien and Michael Moorcock. I’d read about these things, I think Eric Burden had mentioned reading Lord of the Rings, so I was just going along with the general feeling of the time, that escaping into other worlds was worthwhile. It’s the same sort of thing that kids do all the time. But I didn’t really know how to go further than that. I didn’t know about science fiction until later and I didn’t know how to find out about those things. It was only later when I moved to Birmingham that people pushed books at me and then I started getting into Fortean stuff. That was a breakthrough. It showed me other ways to think about science fiction. l remember when I read these things that I was always looking for something to be true, secretly hoping that Middle Earth might really exist. Also, I was always more interested in science fiction than I was about other planets, rather than about inner landscapes. I was always looking for an escape.

Was it like there was some sort of secret area of knowledge and information that you couldn’t get to, and you just had hints dropped to you from people who were there, like Eric Burden?

Yes. I kept expecting that one day I was going to grow up and then I would be vouchsafed these secrets. Also, I always liked creating little worlds. When I was a kid, I was into model soldiers, I liked to paint them carefully and set them up and then get crouched down on the floor to become part of that world. And I would make model theaters, and boxes with peepholes that you looked into. I was always after making little things. And if there was a toy car that had an inside, with seats and things, I was always really interested in what was going on inside there and how these things were so little. I think my reading took that in as well, looking for secret worlds. And I think that led into comics too. I’m sure it did. Part of doing comics is the desire to create or be part of a world that I can control, an inside world, a miniature world. I used to like General Jumbo in The Dandy, the kids who controlled the little mechanical army with a wrist-pack. I was so jealous of him!

So, did you ever feel when you were drawing that you were getting through to some sort of truth?

No. But I was in control. I used to avoid tackling the real world in comics. I was much happier dealing with the stuff that I could control.

It sounds like you were more interested in things beyond the prosaic world anyway. You’d rather be somewhere else.

Yes, absolutely. It’s escapism. It’s the same motivation that makes me not read newspapers. I get the news I need off the radio. The rest of it cuts too close to the bone.

What did drawing mean to you at that time? Did the lack of being able to see a practical application for it make a difference, compared to music?

I didn’t really think about it. I always wanted to go to art college, but only because I wanted to be an art student. When it came time to go to college, I really didn’t know what I was talking about. I was a very naive, undeveloped teenager — socially undeveloped, politically, and just in terms of common sense. When I went to college people suggested that I should do graphic design. To me, graphic design meant designing toothpaste tubes and I wasn’t going to do that. I wanted to be an artist, and paint. So that’s what I did, and I was hopeless at it. I had no idea what I was doing there. I wasn’t a painter; I was just messing around. So, I left after a year. That was when I came to Birmingham in fact, to do that course. It was a three-year course and I left after a year.

Had you turned up there as part of some sort of rock ’n’ roll myth? Because the Beatles were art students?

Yeah, yeah. It was all that sort of thing. I left art college more because I wanted to be a hippie than anything, doss around. But yes, it was all just mythology and imagery. Silly adolescent stuff.

Did you because you had no idea why you were there?

Well, looking back on it, yes. At the time I had all sorts of other reasons. There was a very controversial teacher there at the time, the head of painting, and he came in and upset a lot of students. Quite a few people were quitting around that time, and I was one of those. Although really I had no argument with the man. It was just that everybody else was upset by him, so I was upset as well. I was always a follower-on, and joiner of groups and gangs. I never really formed my own ideas and never really got involved in anything serious. Politics went right over my head: I had no idea what was going on politically at all.

Was there still pressure to be political in 1970?

No. Not at art colleges. The Students Union people used to come round at the beginning of the year, and they would be in disrepair because nobody at the art college was remotely interested. They’d say, ‘‘You bloody art students, we’re trying to do things for you!” We’d say, “Yeah, man, yeah … [laughter] … that’s cool … I ain’t into all that stuff.”

Did you have any sense of direction or purpose?

No. Only that whatever I was doing was going to be to do with drawing and art. And then just before I left art college, I started seeing underground comics. And when I left, I met some people who lived close by to me who were running the underground magazine in Birmingham, Street Press, and that was when I first started to get an inkling of what might happen — really when I first saw Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb and Zap and realized this was what I might do with my cartooning skills.

So, from then on, everything was geared toward that. It took a while to slot into place, but it got that way. It was pushed on by the fact that I’d quit art college and gone to work in the library — this was when jobs were easy to find, and you could go and work in the library in any sort of physical condition. They’d say, “Are you alive? Can you walk? You’ve got the job.”

l was still puttering around at home as well, playing at being a painter. I had a room in somebody’s house which I used as a studio for a little while, and I was producing odd things that were less and less like paintings and became boxes with toys in and collages of sequins and feathers. But really that was down to running out of money and running out of paint and having to use whatever was around. So first of all, I was using the cheapest household paints I could find and then I was using stuff that I picked off the streets, anything at all, old toys. And there was a sort of purpose to this because I was very interested in painters like Robert Rauschenberg and Duchamp and Jean Tinguely, the sculptor, people who were working with random elements in their work and found objects. And then I stopped. I was gradually doing less and less of these collage things and more and more drawings, which were starting to turn into little cartoons.

This was after you’d left art school, and after you’d un the undergrounds?

Yeah. I always did cartoons and copied various things from here and there, but it was seeing the undergrounds that made me actually start working on it, and developing a style, rather than doing something that was totally unformed that I did to give the kids in school a laugh.

Did this have anything to do with the drawings you’d done as a child?

I drew wars then. You know, what kids always draw. We’d get sheets of paper and join them all up and draw a big, long horizon line, and everybody would have to fill their paper with soldiers and tanks, and you’d put them all together and have a huge battle.

What about your teenage years?

Pop groups [laughter]. I was making an almost lucrative living at one point while I was at school by painting pictures of Jimi Hendrix onto bit cardboard and selling them to my classmates.

Can you make a connection between what you saw in underground comics, and what you’d done until you saw them?

No. When the ’60s came in it wasn’t just the undergrounds, it was the whole hippie thing. In Newcastle, like everywhere else, there were hippie shops, and I was starting to see psychedelic posters, mixed in with the comics stuff, sometimes with the same artists.

Was it again associations of lifestyle that impressed you? Or was there something in the art that really struck you?

I think it was the latter. I’d never seen anything like this before or even imagined that it could be. And again, you see, I was a raw adolescent, and one of the things l went for in comics was the sex. I’ve heard people talking about those times and the underground magazines, like Oz and I.T. [International Times], and how there were certain types of hippies who were into the philosophy and the politics, and how there were others who just looked for the tits, and I was one of the ones who looked for the tits, unfortunately. [Laughs.] That’s why I was getting hold of underground magazines, and why I was interested in them.

But did you notice early on who was drawing the tits?

No. It never really occurred to me that anybody was. It only gradually came through that there was this man Crumb who was doing this stuff. I remember seeing this word, “Crumb,” and gradually realizing that this was the bloke’s name, and it was his real name. But then, I forgot to say that I had seen the early Mad books when I was a kid, which did affect me, that was some of the stuff that I used to draw. And did notice that there were artists involved there, after a while. I was only about eight or nine, and they really confused me at first, because it was all stuff that was totally new to me — basically, American culture. I would see these things which were obviously jokes, but which I didn’t understand, because they were about American TV programs and American shops. But I still used to laugh at them, because I could get the idea that there was some sort of weird humor there. And I saw the word “Wood,” carved into the side of a ship or something, and it was ages before I realized that this was the name of the bloke who’d drawn it, and not just some other daft gag. So, there was that, and then I did start noticing that Crumb and Shelton were doing this and thinking I could do it.

Did seeing the undergrounds, and realizing that there were artists who did comics, remind you of the Mads that you’d sun as a child?

Not really, no. I didn’t make that connection at first. I think it was later that I realized that they’d all been influenced by the same things, in a different way. The Mads I’d seen were the Ballantine paperbacks, and there were only one or two. But I do remember that I was aware of the Mad version of things before I was aware of the originals — horror films, and superheroes as well. I knew “Batboy and Rubin” before l knew Batman and Robin, “Plastic Sam” before I knew Plastic Man. So, it always gave me an odd twist on American culture. I think that’s one of the reasons why I latched onto the undergrounds as well. It was obvious they were parodies.

I want to pin down your reaction to the undergrounds a bit more. What were the things that surprised you about them?

That they could get away with doing this stuff. It was a window into a hippie world that I wanted to be a part of — I wanted to do drugs, and they had stuff about drugs, and the sex stuff.

So really it was the content? It wasn’t anything in the drawings themselves?

Yeah, sure it was. Robert Williams always impressed me, with his slickness. And Rick Griffin as well. I liked that smooth, flowing professional style. I think that appealed to me first, that impressed itself on me before Crumb and Shelton. But it was very quickly that I realized that there was something else going on, with Crumb in particular. Shelton, I took a little longer to start reading, maybe because it looked more conventional than the others. Then when I did start reading The Freak Brothers it became my favorite, and it still is. So, there was some of that, some of the style. I remember seeing that there were one or two comics that were always quality, and Zap was one of them, and then there was a lot of other stuff that was rubbish. Because in the early ’70s there were a hell of a lot of undergrounds, there was a real craze for them, and most of them weren’t worth publishing. But you see, I don't remember studying this stuff at the time. I remember that there was a phase when I bought a lot of Marvel comics when I was on the dole and had no money, and I could afford a treat of 9p for a Marvel comic. I used to read through these things, and I can’t remember what any of them were now. Man-God I think was one. Howie … Chaykin? Star-something or-other? Star … Cody Starburst? But it wasn’t looking for fresh inspiration, it was just filling your life with pop. Because it was all just part of other things that were happening, like gigs, and writing songs.

When I spoke to Steve Bell [cartoonist for Britain’s Guardian newspaper], he said that “Crumb went straight to my brain.”

But that wasn’t really the case with you?

Not in the same way as Steve, I don’t think, no. But he’s always been more together in his thinking than I have.

So really the most important thing about the undergrounds was that they showed you something that you could do with your drawings? They were a practical inspiration, more than anything?

I think so. And I saw a way I could become part of this world, by doing what I wanted. But it wasn’t decisions so much as just slipping into this. At the time, apart from a short period on the dole, less than nine months, I had jobs, in order to be able to fund myself drawing comics in the evening. I worked in the library, and I was a postman for a few months, and I did clerical work in a prison.

But at the same time, because you had this example of the underground comics, did you think of yourself as a cartoonist-in-waiting? Did you think that was what you really were?

I did by then. Because I was having stuff published in Street Press, and also gradually in some of the other underground papers around the country, in particular, Muther Grumble in Newcastle. I even had a drawing in the I.T. in London once — pirated, of course! [Laughs.] So yes, I saw myself as part of this. And gradually, from being individual drawings with captions or speech balloons, they became, well, I dread to say “sequential,” because they weren’t, but they were frames joined together. I would make a point of giving all the characters fancy noses and ears and feet, and then making sure that they all changed in every frame. Different stripes, different spots, different lumps on the end. I used to fill the whole page with these things and became obsessive. If I’d drawn the same sky as I’d drawn in the previous comic, that was a failure. I was putting all of these rules onto the comics, and never really thinking about the writing. The writing tended to be grabbed out of the air around me, from people chattering and records playing. There were a lot of people around at the time, sharing a house and having parties, and we’d pick up pieces of drunken conversation and stoned conversation, things that were funny at the time, things which became private jokes purely because they were written down. I’ve got files full of that, I was sometimes drawing three pages a night.

When your style started to come together, as the ’70s went on, there seemed to be quite a strong influence from British children’s comics, from Leo Baxendale and Ken Reid, whether you knew it was them or not.

I didn’t know it was them, but yes. When I started drawing comics, I was deliberately and consciously trying to make them like these American comics, but with a British bias, and looking for ways to bring in bits of The Dandy and The Beano. I also bought the Penguin Book of Comics at around this time, and that was quite an eye-opener as well because I discovered stuff about the history of comics that I had no idea of — in particular, Krazy Kat, Herriman, that was the other big influence on me. I was really turned on by the fact that they were poetry, and that they were in a secret language, and I started trying to be Herriman as well. Of course, you can’t be Herriman. Not just like that. He came up with quaint and esoteric things, and what I came up with was just silly nonsense.

Presumably, there were only a few panels or pages of Herriman in this book. Could you see immediately that it was poetry?

Well, I read that it was poetry in the text, you see. [Laughter.] And then I read the strips and I thought, “Yes, it must be.”

The backgrounds in your strips were like Herriman from very early on.

They still are, to a large extent. Dotting the “o”s — l always used to say that I dotted the “o”s as a tribute to Herriman. Then Paul Gravett pointed out to me that Herriman didn’t dot his “o”s. [Laughter.] I’m sure I saw him do it once!

I’m interested in the fact that you were influenced by people like Baxendale, and people like Crumb at the same time. I wonder if they connected in your head at all?

No, I don’t think so. Like I said, I was using the children’s comics to try and anglicize the undergrounds, but also to keep them innocent. One of the things that I couldn’t come to terms within the undergrounds was adult sex sensibilities. I was interested to read the stuff, but I never really wanted to draw it. I never wanted to do sex and drugs and rock and roll. For a start, it always seemed too easy a subject. So, I was after doing … Well, I don’t know what! But I didn’t want to do those things. Also, I wanted to do stuff that I wasn’t ashamed to show my mum. And one way of doing that was bringing in influences from the kids’ comics and using children’s comic language. I always felt that Crumb’s and Shelton’s characters had a sort of personality to them — they were streetwise, they were in charge, and my characters always felt like innocents abroad. In a way, I think I felt the same myself. I always tended to feel that, in any given group of people, I was the least experienced. There was a feeling of discovery, but of knowing that I was only on the verge of making this discovery, that I was very much at the beginning of whatever it was. I had no idea what the discovery was because you don’t find out until it happens. But certainly, I felt very inexperienced, and I was always anxious about that inexperience.

Was this what you felt when you were drawing, early on?

Well, in a way, no. In a way, doing the drawing was where I could control things. But that was inasmuch as I was controlling what was going on the page. What the influences were coming into it, and how I was writing it — I did feel very innocent and inexperienced about that, although again, I couldn’t have admitted it at the time, because I didn’t know it at the time. It’s only looking back on it now that I see this sort of thing. At the time, I was ready for anything, jumping into any sort of adventure. There was lots of careening round town in vans with no doors on, people wearing flying helmets, all sorts of odd drugs going down. The usual, the usual.

Looking back, do you think there was something quite childlike about the life, and about the work as well?

I don’t know about the life. I’m surprised I made it through, actually, in many ways. Although I don’t think we ever did anything fantastically dangerous. There was never any heroin or cocaine or anything like that around. We used some LSD and other rubbish psychedelic drugs. But it never really got out of hand, I don’t think. Maybe it did for other people. But … I used to go to bed before it got out of hand.

But by that time, you’d managed to crack the alternative lifestyle …

Not really, no. I was constantly falling short, and I had this constant awareness that other people were having a better time than me. I didn’t go to clubs, because I couldn’t afford it for a start, and because I didn’t know where they were, and nobody ever said to me, “Let’s go to a club tonight!” Or if I actually did go somewhere, I’d as often as not, not be allowed in because of the way I looked, which tended to get pretty weird around that time. We’re talking about the early to mid-70s, ’74ish I suppose, and I was wearing eye makeup and psychedelic paint on my face and sequins around my eyes, and I had my hair dyed black and red, and I used to wear odd clothes and a big floppy hat, a long fur coat. And my brain was fried, and I had very long hair. It was generally pretty sleazy and sordid, looking back on it all. Pretty crummy all around. Some people I think had a glamorous early ’70s, but mine was pretty seedy, although I thought I was having a good time.

It seems like you had a lifestyle that in some ways was breaking barriers, and letting you do things you hadn’t done before, which presumably was true of the comics as well. But was there still something quite safe about both processes?

Probably, yeah. I guess my concept of safety in those days was not one that would really hold good when I think about what we were in fact doing. Mandrax and cheap wine, that wasn’t very sensible to do. But all in the past, all in the past. I was aware quite early on that! had a quite specific drawing style that was peculiarly my own, and that people recognized, and that they liked, which I suppose was comfortable. The stuff that was going into the early Street Press things was popular, certainly around Birmingham and with people I knew. I became “their” cartoonist, and that was nice. I was always after doing stuff that was friendly and accessible, and funny. I never had any desire to do serious comics at all. It never occurred to me that that’s what they were for. So, I think people took it to their hearts, and I started to gain a following of some sort, people who recognized the drawings. And I think you’re right, they were kind of … not exactly middle of the road, but they were safe, and they were comfortable and they were friendly drawings. And I was deliberately trying to make them popular. I wasn’t exploring the insides of my head, I wasn’t using it as a catharsis, like a lot of people seem to do. That was never my intention. In fact, l deliberately masked that sort of stuff most of the time. I still do. I’m not comfortable doing autobiographical stuff. It never seems to be very interesting, especially mine. And it always seems a bit of a con, in a way. Why should anyone be interested in my life? I’d much better spend the time inventing a new story, which has actually got some value to it.

Did that style that you’d arrived at by this time come quite naturally out of the drawings you were doing already? Having experienced the undergrounds, did you end up with stuff that was yours?

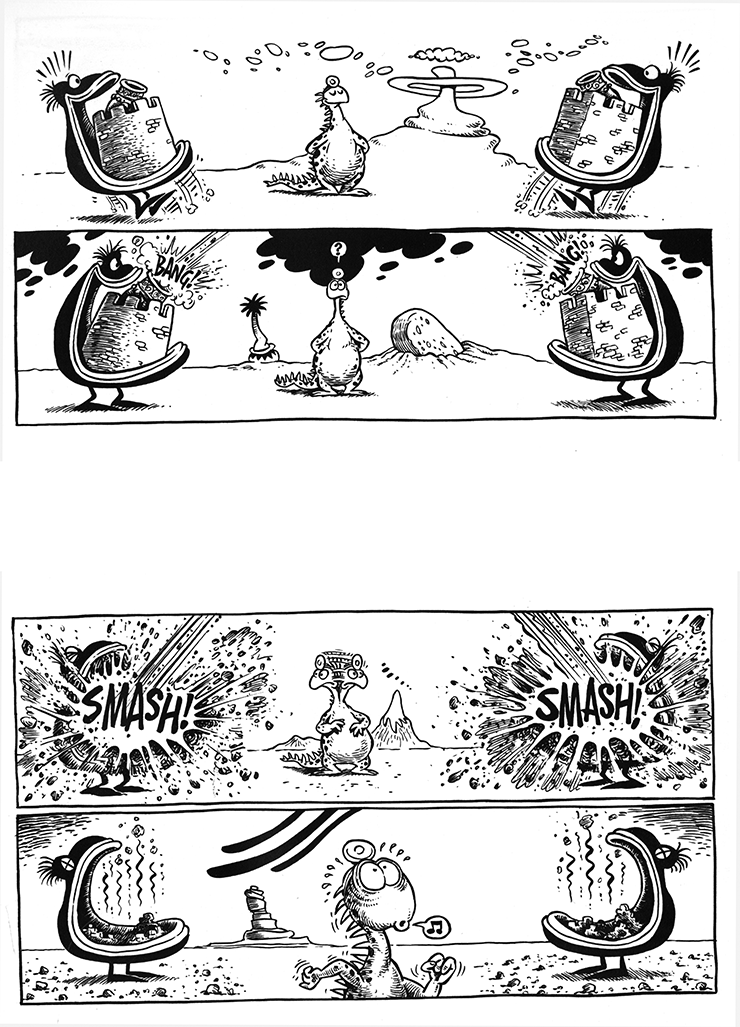

I think so, yeah. Because they didn’t look like the English kids’ comics either, not even remotely. Some of the speech balloons had that flavor, and there was a general air of innocence, but the characters used to truck around the place, as in “Keep On Truckin’,” and I used to look at the way that Robert Williams drew Cootchie Cootie, and work on that sort of character. I was interested in doing psychedelic, anthropomorphic stuff — little demons and potatoes, and things that walked around with their noses in front of them, not joined to their heads. I liked making experimental drawings like that. But I never got myself down to drawing real people, real characters. That came later.

Were you just being playful?

Mm, yeah. ‘Cause it was a playful time for me. I was much more interested in the play side. There’s a book called Play Power, by the old editor of Oz, Richard Neville, which is about the whole ‘60s hippie philosophy of play as a cultural phenomenon. I remember reading that and being impressed by it. But again, I also remember skating over all the stuff about politics. I didn’t understand it. I really didn’t understand politics at all. I had no idea what was happening. I wasn’t very in touch. I didn’t watch television, even then. I’m still not very in touch. Although I listen to the radio now.

Has that idea of play fallen away from you a bit?

To some extent, yes, because now it’s a business, it’s a job.

It must have been strange to have a following as a cartoonist when you describe your earlier life as following and tagging along with one group after another. It must have been good to provoke other people’s reactions.

Well, in a way that’s what I’d always done drawings for. Even when I was at school, I’d do drawings on a blackboard or on a book, and everybody would crowd around and watch what I was doing. It made me the center of attention, and popular.

Do you still get pleasure from that? Or are you more sophisticated and past it all now?

Ooh, I think I’m much more sophisticated now. [Laughs.] No, I’m sure it is, I’m sure it’s mainly to do with wanting people to like me. I think that’s why I don’t do serious stuff, because I can’t help feeling that people would feel cheated, feel imposed on, if I tried to get them to read serious stuff. What business has he got trying to teach us anything, or tell us stuff?

The way you draw yourself in strips makes you seem very diffident and nice — which I’m sure is the case …

I don’t know about that. I’m sure you’d find people who’d disagree with you on that. Drawing yourself is like drawing the shape on the inside of your head rather than the outside. Have you ever seen these drawings where they draw the human figure, but in terms of where most of your nerves are? So, people have huge hands, and huge noses and tongues, and huge genitalia, and very small backs, and very small backs of their legs, because there’s less nerves there? You get this strange, distorted figure, which is obviously human, but which is much more to do with how we feel than how we look. In a way, it’s that sort of thing. I draw myself as I feel from inside. I draw myself with a bigger nose than I have, and a bigger chin and a more receding forehead.

I remember the first picture I saw of you was on the back The Big Book of Everything, and I thought you were some sort of Ivor Cutler figure [eccentric, surreal Scottish poet], about 70 and very strange.

Yes. People have said that before. I had my head shaved then, cropped very close. I was saying about wearing all this crazy makeup. Well, later on than that I used to dress, not exactly like a skinhead, because I used to wear all sorts of odd things, but I did crop my hair down as close as I could, with these ferocious little round spectacles, and ragged jeans and ragged jackets. And really, as with the makeup before, it was a mask. It was a way of keeping people at a distance, frightening people off.

Have you ever tried to do that with the comics when you’ve appeared in them? Have you ever toyed with the idea of creating a persona, so that the readers of your comics could get some idea of you that wasn’t really the case?

No, because that would involve making myself into a sort of antihero figure, or a more negative figure — a powerful figure, I suppose. Which is not how my comics work. It’s certainly not how I work in comics. I’m not a powerful figure in them.

EARLY DAYS

Let’s get back to your prehistory. You started working at a photocopying place at Birmingham Polytechnic, 1971, I think.

That’s right. I started working with a little printing machine, just a step up from a photographer, really, but adequate. And it was there that I started publishing — well, making my first comic books, which were four pages folded and stapled. The first ones that I drew, I didn’t realize that you could draw them bigger and reduce them, so l drew everything “real”-size, and I also drew the sheets as page one and page 16 on the same piece of paper. Didn’t realize that you could do all of that later. I was calling the thing Large Cow Comix, for no reason other than it was something to put on the title, and it filled in a half-hour while I was lettering it, and wondering what to put in the first frame, and it was the silliest thing I could think of. I did four of those, 200 at a time.

You moved on to the Birmingham Arts Lab’s printing press in 1973, with I know is when your comics work started to develop. What kind of people were you working with?

The staff of the Arts Lab were originally painters and sculptors and actual practicing artists, but they quickly became arts administrators, and there were people involved with avant-garde theater and cinema — Andy Warhol films, Kenneth Anger, poetry, and there was a silk-screen workshop. All sorts of things used to go on there, it was very stimulating, very exciting, because it was absolutely the sharp end of contemporary arts. I bagged a job as a print operator, which I was no good at, and I became a designer in 1976. A bunch of us ended up running a press, mainly due to a man called Martin Reading, who pushed for the press to operate as a legitimate, profit-making operation. I was designing leaflets, posters and also comics. Paul Fisher was — I don’t really know what Paul was doing, but he was part of the gang, for sure. Later on, a guy called David Hatton came in with us, and he’s still a printer. If I want anything printed, I go to him. So, there was this gang, and we started publishing my comics — Zomix Comix, and a book called Dogman, which was something Paul Fisher had written and performed as a monologue in rhyming couplets, and I did as a comic. That was the first “real” book I had published. That was fun. We did it as a stage show when we published the book. We made a stage troupe with friends from the drama college, Martin built big stage sets with canvases, I painted Dogman cartoons onto them, and we toured around theater festivals and folk clubs and church halls.

Was this expanding your ambition as a cartoonist, or were you getting a bit distracted from that?

Well, I was expanding my ambitions back into music, because I still fancied myself as a performer. I used to write songs and play guitar. They were crap songs, absolute rubbish. But I really liked performing, and I still do — I like being on stage. So doing Dogman satisfied that a little, although I was an actor in that, not a musician. I also played off and on with a loose collection of musicians and performers. Because we were working at the Arts Lab, and because there was so much stimulating activity going on around us, we all tended to branch out away from doing strictly comics. So, when we went on from doing Dogman to doing other comics — and this was after we’d seen French comics for the first time, in Metal Hurlant, which was a big stimulus — we wanted to produce something experimental. The fact that we were working directly with a printing press was always an influence on us. It was as though the press was a fifth member of the group, rather than being a tool, it was part of the creative process. We were doing things like creating comic pages in the darkroom, that didn’t actually exist in artwork terms, but were done by putting things down onto photographic paper and exposing them to light, collaging things up.

What were your aims for the cartoons that you were doing then?

Just to do ’em! Just to do ’em! Everything was a struggle to make money, to make a thing of some sort. We used to get paid by the Arts Lab, and we would periodically take cuts in pay, as the place gradually went more and more bust because it was so good to work there. We were supposed to make money by publishing and selling the comics, but we never did sell that many, because we didn’t have the distribution, that was way beyond us. But whatever I was doing, it was always with the idea that one day, this was going to pay off. I was never into doing it purely for myself — although I did it for myself, and I produced a lot of stuff unpaid, it was all with the idea that this was towards a career.

What sort of scene was around you at that time, in the early- to mid-70s? What gave you the ambition to think that your work won’t be seen? Because I imagine the counterculture scene was tumbling down around you …

I wasn’t that planned about it. I didn’t really think towards the future in that way. I wouldn’t have known how to have ambitions or make plans. I just knew by this time that what I was doing was cartooning, and I took on all sorts of jobs to make a living at it. Anything at all involving drawing I would take on. I didn’t know there was a comics scene or comics fans until I started to get letters from them, asking for copies of Large Cow Comix. That was the first clue I had that other people did these things in the way that I did.

It sounds like you created your own path as you went along, not by any brilliant strategy, but just by …

By carrying on, yes. A path appeared behind me, really. And immediately closed up so that nobody else could follow through it. I started to build up a network of customers who wanted me to design things outside of my Arts Lab work, and gradually they left Birmingham and got jobs. So, a network formed around me, through my work being accessible and funny populist. People liked it, and it was very distinctive, so people came back to me. I was also probably the only cartoonist that people knew.

Did you have a need to be a cartoonist by that time?

I did feel that. As much as anything it was a way of shutting myself off. I needed a lot of time to do the things, so I would take this time, and destroy my social life because of it. And I was doing more and more work. I was working full-time at the Arts Lab and picking up more and more freelance work as well. Eventually, I was doing two jobs. And we used to work long hours at the Lab — we weren’t shirkers at all, we weren’t slackers. I’d work 8:00 until 8:00 there, and then I’d work on until 2:30 or 3:00 in the morning, cartooning. After a year or so of that, I went freelance.

It sounds like, just as much as you decided to become a cartoonist, cartooning took you over.

Well, it was what I was doing, and it was paid. I’ve always been a good worker, and apart from one brief period on the dole, I’ve always had employment, and I’ve always been determined to have employment, I didn’t like being on the dole. So, I’ve always been the sort of person who says, “No, I’ve got to finish this,” rather than, “I’ll leave this and go out to the pub.” And that’s good, it gives you a good reputation. I very rarely miss deadlines. And I was making money out of it, I was starting to earn a real living at it, especially when I picked up some advertising jobs. So, it was further and further away from the idea of being an independent cartoonist. I always felt much more of a jobbing cartoonist. In a way, I’ve always been surprised that I’m an “underground” cartoonist because I’ve never felt particularly “underground.” I’ve always been a working cartoonist.

THUNDERDOGS

I think it was while you were still at the Arts Lab that you did Thunderdogs, which was your first major comic.

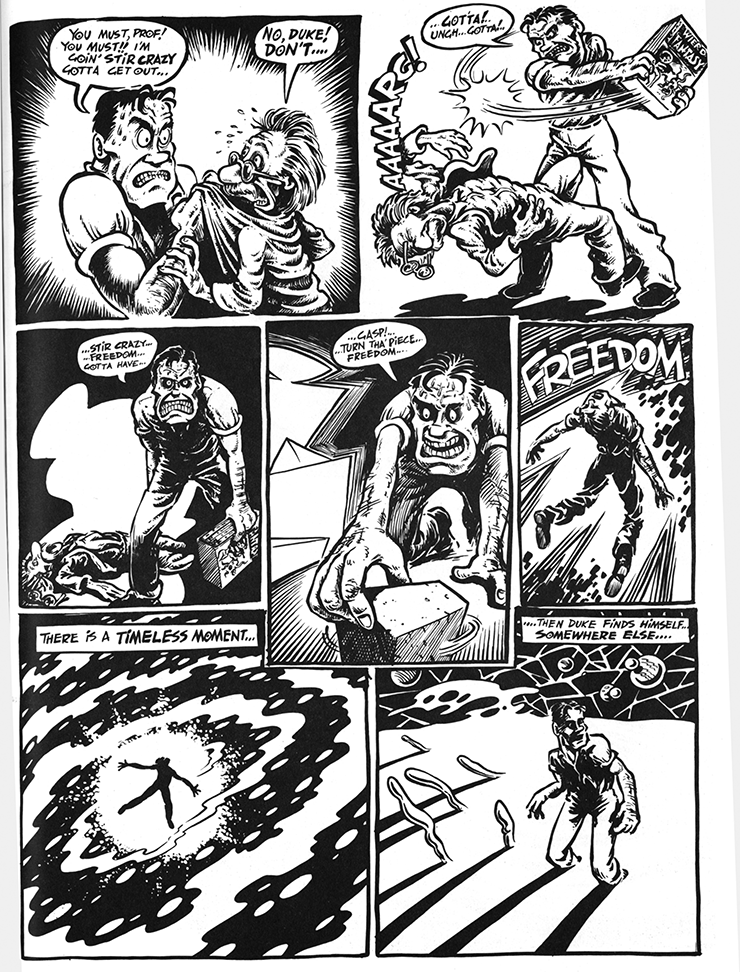

That was in 1977. I’d actually just left the Arts Lab, and it was something that I started drawing quite sporadically. I started by making a model kit of an aeroplane. I was sticking a tank chassis onto the bottom of an airplane and sticking a hand on the top with an engine in, and I thought, “This looks interesting, I’ll draw it.”

So, l never finished doing the model, I drew characters to go with the airplane, and this turned into the Thunderdogs comic. It’s a story of transdimensional tomfoolery, a gang of paramilitary idiots led by Major Mongrel, again kind of based on the old Mads, like Wally Wood’s “G.I. Shmoe,” and also to some extent “Black and Blue Hawks,” which was a parody of Blackhawk, but which I swear I never saw until years later when Gilbert Shelton showed it to me. The story is that Major Mongrel gets separated from the others. He goes into a two-dimensional universe, and they stay in a three-dimensional universe. And the 2-D universe is comic book pages. The only information Major Mongrel was given was that he was between pages 20 and 21, and the actual drawings are of the backs of the pages, as though they were canvas with wooden struts, which the characters climb between.

Did you feel you were making some sort of breakthrough, as you carried on with this?

I was making it up as I went along! [Laughs.]

Clearly.

It took about three years to do in the end because l didn’t know what the story was.

But just because of the length of it …

Well, I didn’t know what it was going to be when it started. I started at the top corner to see what happened, it was more or less a doodle. Then I went to the States in 1978 and I met Gilbert [Shelton]. I’d been visiting Trina Robbins, who shunted me around to just about every female cartoonist in the West Coast, and as well as that we went to Rip Off Press. Gilbert saw Thunderdogs, half-finished, and said, “We’ll publish this.”

It took another two years to finish the thing, but eventually, it was, and they did. They did 10,000 of it, we brought 3,000 over to England, and most of the rest were destroyed in the Great Rip Off Press Warehouse Fire. Then the others were destroyed in a flood.

Was Shelton a hero to you? Were you impressed to be there?

Oh sure, you bet. There was a big Halloween party at Trina’s while I was there, and there were all these old heroes of mine, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton, Ron Turner was there, God knows who else. I got drunk, and when I get drunk I get kind of introverted, so I spent most of the evening sitting out on the back porch, too shy to talk to people. So, I didn’t get to meet them! The story of my life.

When you met Shelton, was he an impressive figure? Did you feel he was on a different level?

He was older, 10 years older than me. And he was in a big professional-looking studio, even if it was only the Rip Off studio, with a Ping-Pong table.

Did he look professional?

I didn’t really know, I didn’t know what a professional looked like, I don’t think I’d ever met any. There was a drawing desk in the corner, I remember, with a rubber chicken hanging from it, and this desk was the one where, when people came nosing around the place, saying, “Hey, is Larry Rippee around?” They’d say, “Oh, that’s his desk there, you just missed him, he just went!” [Laughter.] “Hey, is Dave Sheridan around?” “No, that’s his desk, with the rubber chicken on it. You just missed him!” It was the decoy desk. But it was impressive because it was all the things that you’d read about on the back covers of the Freak Brothers comics — the Ping-Pong table, and the laidback atmosphere. Gilbert rolled a joint, and it was just like a Freak Brothers joint.

Did you feel like you’d arrived?

I was chuffed to death. I got my photograph taken outside the Rip Off Press offices. Really chuffed, with my hair bright orange. I’d dyed my hair blonde while I was in San Francisco. That freaked them out because they were still all hippies. I came out of the bathroom with my hair peroxided, and they thought I’d gone out of my mind.

Were you their first version of punk?

Well, it was 1978, and punk hadn’t really hit San Francisco. When I was walking around with Suzy Varty, who’s been my traveling companion on many adventures, we found this boutique run by a guy who had obviously been to Seditionaries in London, come back, bought a lot of T-shirts and thrown paint on them, and was charging a hell of a lot of money for them. He clocked that we were English, and started getting very shifty, very nervous. But we weren’t particularly punk. We were just how everybody else in this country was. But where we’d turned up, on the West Coast, we were freaks.

Was it the first time you’d been to America?

The only time.

Did it impress you?

I was too wrapped up in myself to notice, really. San Francisco was very pleasant, very laid-back, I had a good time there. Then we went to Tucson, Arizona, and that was smashing, really laid-back. From there we flew to New York and got dumped in the middle of the city at half-past six at night, and couldn’t get in touch with our contact there, so we started to feel a bit of panic, having come from the desert, where everything was four times as slow, and with the dark coming down. So, we booked into a hotel on 42nd Street, closed the curtains, got stoned, started poring through a Street Plan. The next morning, I could deal with it. I never really liked it, but I never got to see it properly. I kept taking the wrong turn and ending up in the Bowery.

Was the whole thing like an adventure? Was it like all your best hippie dreams come true?

It was more of an adventure in that it wasn’t all pleasant. But that was my fault. I was very introverted, and I used to get closed off — still do, I suppose. I am shy in public, I don’t open out very easily, especially if I’ve had a drink or two. I tend to doze off in the corner. That was the case then, as well. We got dragged to posh discos, and I didn’t even know what I was doing there.

Was it like there was an adventure happening around you?

Yeah, but I wasn’t really aware of it. l was waiting for the adventure to start, and it never quite did.

During that period, when you knew that Rip Off was going to put your comic out, did that make you feel differently about things? Did you feel that you were really on the way?

Yeah, l did actually. I was very pleased and proud to be the only English cartoonist to have his own book in the underground press, published in San Francisco by Rip Off.

Did that change your work? Did it make it more coherent?

Well, I was starting to get more coherent by then anyway. I’d started planning The Big Book of Everything, which was originally a joke about something which would be useful to have, and I’d started drawing comic books as chapters, each one telling you about something scientific, from a nonsense point of view — things like Mrs. Newton learning how to cook before Isaac invented gravity, nailing the sandwiches down. The book became a general mixture by the time it was published, but I’d started to tie the stories down much more, and Thunderdogs was a big exercise in trying to have a coherent storyline. I still wasn’t going to the trouble of writing the thing beforehand.

When narratives do start occurring in your work, they’re like that story in The Big Book where Alan Rabbit is faced with the synchronous universe.

Oh yeah. I drew that while I was tripping.

So, everything seemed wry synchronous at the time?

It tended to.

But the plots are like these pinball coincidences, they’re like ricochets.

Well, that’s because of another interest which had grown around this time, which was in Fortean phenomena. Carol Bennett introduced me to the editor of Fortean Times, Bob Rickard, in the early ’70s, and I agreed to do some work for him. This was all new to me, about flying saucers and things, and l started to get very immersed in that, and to read around it quite a lot. So, I was reading a lot of science fiction at that time. I can’t remember any of it now, I was reading SCIENCE FICTION, not individual books. And also, I was reading popular cosmology, about black holes, and coincidences were coming into that — theories of coincidence, and to look at the world in that sort of way. The psychedelics tended that out as well. Synchronicities happen when you’re on psychedelics, or they seem to. You were always looking for deeper meanings in things and looking for patterns.

Did you find them?

No, no. You just found odd synchronicities. I’m older now, aren’t I? And I know that’s just nonsense. [Laughs.] There isn’t anything there at all. It’s our minds that put patterns onto things, the patterns aren’t there in nature. But at the time it all seemed to link together very well, there seemed to be grand patterns to the universe.

Are you still interested in those patterns?

Yes.

Do they still come out in your work?

Yes, they do. When I write stories, they largely seem to revolve around coincidences. The characters don’t do things, they have things done to them. I think it’s one of the amusing things about the world, the way these nonexistent patterns show themselves. At the Fortean convention, I heard a talk about ley lines and shamanism, and the link between the ley lines, which the speaker, Paul Devereux, reckons to be death tracks, where the corpses and therefore their souls would be taken on a straight-line journey. This is all to do with shamanism, and it applies to cultures all over the world. And once you start looking, you find links everywhere.

Do you know why that interests you? Has it to do with what you were saying earlier, about secret knowledge?

Other worlds, yes. I think that we’ve lost such a lot in cultures, and it may be there are secrets in old ways of living and thinking that would benefit us. I’m sure there are. We’re not going to go back to it, unfortunately. I think the world’s going to hell on a hand cart. Things like the dream time of the Australian and American native peoples, and the shamanism in Lapland, there must have been something to it, or they wouldn’t have done it for such a long time; they wouldn’t have used these things if they didn’t work. We’ve lost the ability to look at it properly now, largely as the result of Judeo-Christian ways of looking at things. Paul Devereux was saying that primitive peoples had soft-edged egos, and our egos have hardened up now, and become more enclosed, as part of Western agriculture, which involves enclosure, and has had an effect on our heads. We see things in more of a personalized, fixed way, whereas primitive people seem to have been more in touch with each other, and to have blurred the distinction between themselves and the outside world. I think that bears investigation. If ever you have experience in mysterious places, wilderness places, there’s something there that you immediately feel connected to. We tend not to stay in these places long enough to find out what the thing is, but there’s a connection there somehow, which we should know more about.

Have you had those wilderness experiences yourself?

To some degree. When I was in Finland last time, I spent the night out in a log cabin in a forest by a frozen lake, and that’s as wilderness as you can get totally isolated. I’ve never experienced silence like that. And l remember being in the desert in the States, having the same sort of feeling. These things come from time to time. The wilderness I can find is just by myself in a field. When I talked before about liking toy soldiers and little worlds, l was always burrowing to the bottom of hedges, and rotting around in tree roots and underneath things. I was always interested in looking down inside things, microcosms within macrocosms. And: I can still do that. Get my face down into the grass, and that’s a wilderness. With a little bit of help and a little bit of effort, l can still get that kind of experience. I suppose it’s called relaxing. [Laughs.]

So, do you think you can get back to the old ways?

No, l think we’re too far gone. But possibly there are new things to be made from them.

Do you still take drugs as a way of increasing your perception?

No. Because it doesn’t do that. I think people tend to find new things when they initially take psychedelics, but like all drugs, you continue trying to get the original thing back again, and it never happens. As to whether it happens in the first place, I don’t know. It seems to.

KNOCKABOUT

I want to follow your career in the ’70s a little further. When did you get to Knockabout?

In about 1978, I think Carol Bennett, who I’d know in Birmingham, phoned me up and said she’d got together with Tony Bennett, and they were starting a project, and would I like to be involved? I was pleased to be because we’d just wound down the Arts Lab by that time. We’d stopped publishing comics because we were wasting too much money. So, I was wondering what might happen next when this came up. It was perfect. Carol said, “We’ve got a great name for it, too.” I said, “What’s that?” and she said, “Knockabout!” And all I could see were letters that were going to have to be fitted into a masthead.

But I started working with them. They imported Thunderdogs from San Francisco, and that was my first comic through Knockabout. Shortly after that, they also did The Big Book of Everything. And they were publishing The Freak Brothers as well, which was how everything was working, and still is — Knockabout runs on The Freak Brothers, basically. Since then, Knockabout’s gone from strength to strength, in small steps. It’s been quite a long time, but they’re still in business.

Are they really important to you?

Yeah. For a start, they’re two of my best friends. We’ve gone through a lot together and made lot of decisions together and … In a way, we’re a team. It’s difficult to think of Knockabout without all the three of us in it. I think we’re seen as a team. I do have a financial stake in it, not to a great degree, but I am involved. I’m known as a Consulting Editor, not just a contributor, and of course, Knockabout has first call on any comics I do. And they’ve been good people to work with. They’ve never made me rich, but I don’t know that anybody else would have done that either. They’ve also never made impositions on me. They’ve always been happy to let me develop whatever it was I wanted to do, and not to make me look for a commercial way of doing things, because we’re none of us into the mainstream.

Do you think Knockabout’s quite important to British comics?

Mm, you bet. In a small way, because they’re a small publisher. But they’re one of the oldest established comics houses now. Knockabout’s still there, it struggles on, and is always imminently in danger of collapsing, but we’re still going. We’ve made mistakes — we got involved in the graphic novels scam, just like everybody else, when the market wasn’t ready for them. But we’ve hung on, and now Knockabout leads the field. I do honestly believe that — that we publish the best because we’ve got Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb … But also, Knockabout leads the field in terms of ideas, and readiness to have a go at new things, and we’re respected for that.

Do you contribute to that editorial side?

I try to, yes. It depends how I’m feeling, and how busy I am.

Would your life be more difficult without them?

Well … I wouldn’t know what to do with my comics, actually. I don’t know who else would publish the things — not in the way that I do them.

I know you don’t feel comfortable talking about Knockabout’s censorship trial directly, but could you talk about it as a general issue? Because right through the ’60s, up to the Oz trial in the early ’70s, there were high-profile literary obscenity trials in this country which in every case, sometimes on appeal, ended ill favor of the arts concerned, and it seemed like the walls were tumbling down. So that now American Psycho can come out here and no one blinks an eye. But the authorities seem to still feel that they can kick around the “low arts” — comics and video — as much as they want.

It’s because they’re ignorant arseholes and they don’t know what they’re doing and they’re always looking for an easy solution to their problems. It’s the same reasoning that used to say rock ’n’ roll music was behind juvenile delinquency which was behind the downfall of the country. They’re avoiding the issue. The issue is that people are capable of looking after their own minds and organizing their own censorship if they want. The issue is that they want jobs, they don’t want to be censored, but of course we have a government determined to impose fascism on us. Merely by the fact that they’re there they’re fascists.

Do you mean by being a government, or by being censors?

By being in government.

Any government?

More or less.

There seems to be a vindictiveness to the process.

It’s power. You have to remember that these people will do anything at all to hang on to power. Don’t trust them an inch. Don’t give them anything.

Why do you think they bother with comics?

It’s easy. They can look at them, see the stuff that shocks them, it’s easy to see. And they’re small-minded people. Narrow-minded bigots.

Have they been surprised, do you think, at Knockabout causing such a fuss about their decisions?

Well, you’re dealing with people who aren’t going to change their minds. They may be forced to do so by law, but that’s not going to change their attitude to things. What Tony finds dealing with Customs is that it’s an ongoing thing. He has a sort of agreement with the bosses there that he’ll show them the material he wants to bring in and they’ll say yes or no to it, to avoid having to be prosecuted as much as possible. But they’re not saying yes or no because they think it’s more or less acceptable. They’re saying yes or no because they realize that they’re not going to be able to prosecute us. You’re never going to alter their attitude that This Is Sin. So, you get the odd one, the “inexperienced officer” who takes it into his head that he personally doesn’t like this and thinks everybody else should be offended by it. He maybe told by his superiors that this isn’t going to work, but it’s not going to change his attitude, or theirs. Because they’re ignorant arseholes. I despise and hate them.

Have you ever had any trouble with them personally?

No, but then l avoid being too controversial. There again, I’m inured by Firkin, and because so much of my work is about sex, and I forget that other people don’t take it the same way. And I’m surprised when people are shocked by it — these are people that I know sometimes. They see things and say, “Oh God!”

But it’s just another drawing for me. I forget that my views on these things are probably different to other people. I’ve been twisted and perverted by the work. [Laughs.]

THE BIG TIME

I was interested in what you said earlier, about being surprised that you were an underground cartoonist, because your characters, like Alan Rabbit in The Big Book, and Max Zillion in Jazz Funnies, are the kind of characters I associate with a Warner Brothers cartoon. They’re strong, defined characters, exactly like ones which have become very popular in the mainstream. Do you think it’s an accident of the marketplace that you’ve never been like that, and that you’ve been stuck in this alternative ghetto?

Maybe it’s just that the stories weren’t good enough. I’m only now learning to write proper stories — and maybe in a couple of years I’ll be saying, “It’s only now that I’m learning how to write proper stories.” [Laughs.] I look back at things I did two years ago, and think, “How the hell did I get away with this?”

It sounds like a huge gap because of what’s happened to these characters, but the gap between Max Zillion and Bugs Bunny is not so huge, in terms of the defined concept, and how approachable the characters are.

Well, like I was saying before, I always wanted to make them easy. If people have to struggle to read the things, then they’ve failed. It’s one of the things that I don’t like about a lot of the new independent comics that I see. There’s too much in there that people are too obviously doing for themselves, and not for the reader. Unless my eye flows over it, I tend not to read the things. And if my eye’s got to flow over things, then for the general reader it’s absolutely imperative, otherwise, they’re just not going to look at it. I try to do my stuff for people who don’t read comics because I don’t really know many people who read comics. Certainly, none of my friends or neighbors read comics with any regularity apart from the ones I give them unless they’re cartoonists themselves. And a lot of my friends I find don’t know how to read them. They really don’t know what they’re looking at. When I show them my stuff, they can read it, so that must be working somehow. I’m deliberately doing this — my drawings aren’t simple, but they’ve got to be clear, there mustn’t be any ambiguous bits, I have to keep the number of words in the speech balloons down.

So, is it frustrating that the way things have turned out, you’re still seen as alternative and marginal?

Cult is the word. [Laughter.] Yes, it’s frustrating. But then I have to judge that I’m not commercial material. Or maybe it’s to do with Knockabout being an independent. Our independence does mean a lot, you see. There’s no argument or hassle at Knockabout about who owns the copyright. If you do work for Knockabout, you get paid for it, and then you own it. And: Tony pays probably better rates than anybody else, he always has. It may not be much, because it’s not a big print run, but it’s 10% rather than 7 or 6%.

Are all of those things important enough to sacrifice the possibility of mainstream success?

Well, you see, looking at the mainstream, I don’t see that there would have been a success there. I gather that the big names in the States for example, the respected names, like Jim Woodring and Chester Brown, have day jobs, don’t they? So, they’re not actually making a living from doing their comic strips. Now I’m not making a full living doing comic strips, but I’m making some living at it. There was a time a couple of years ago when all my living came from comic strips. I’m back to doing illustration work as well now, but I don’t feel as though I have a day job. And what would be the mainstream success? What is a big success? Neil Gaiman? But that’s not what I do.

There’s some hole where you should become like Chuck Jones, someplace that doesn’t exist.

Maybe, maybe. It’s my own place. Me and Gilbert and Robert Crumb. We get associated a lot in France and Germany, the three of us together. Shelton, Crumb, Emerson … The three names that come up as the Three Underground Cartoonists. That makes me very proud, to be associated with them. I feel as though it’s not warranted, really, because they’re much bigger figures than I am.

Do you feel like you’re a generation down?

Yeah, and not only in age. But I suppose because I’m fairly prolific, and people see that I come from the same place as them … It means that I pick up some work, at least. When people in France are looking for underground cartoonists, they think of me too.

One of the things I like about The Big Book of Everything is that it doesn’t look like an alternative comic, really. It looks like something for children, with that title and all those characters on the front. Would you have liked it to be a success with children?

Well, not when I was doing that. ln fact, not now. I can’t write for children, really. I’ve never seen the necessity for it. Again, you see, comics for me are funny, not serious, and also comics for me are for adults. The idea of doing children’s comics is a different world, a different job. But what you’re saying about The Big Book looking different was one of the problems. That kind of book was a new artifact which is still fighting to find its place in the market. It doesn’t fit into any recognized categories. They had to open humor sections and comic sections in bookshops when everybody started producing these graphic novels. And of course, what happened was that people who’d read about these new adult comic books in the press, comics with subject matter and writing worthy of an adult, would go into bookshops looking for them, and what they would find were collections of Judge Dredd. This wasn’t what they were looking for, this wasn’t adult, so they’d walk out of the bookshop and not come back. And the bookshops got really pissed off with this, because they’d had to invent a new category, and it had reneged on its promise to them.

Bringing The Big Book out seems another example of this accidental path that you’ve wandered along — to have a whole category opening up around that time, to encompass what you’d just done.

Yeah. Because it wasn’t going into the comics shops, either, they didn’t have a section for it. I sometimes wonder if we wouldn’t have been better just doing comics rather than books, and for me to have flooded the market with 30 or 40 comics, not 10 books. But things happen the way they happen, and at the time the idea was that people would produce books. And they’re nice books.

CALCULUS CAT AND SERIOUS JAZZ

I think you invented Calculus Cat and Max Zillion as characters around the same time …

Yes, I was inventing a lot of characters around that time, and often they came from doodles. Calculus was a doodle. Other times, like Alan Rabbit, they would just arise. I would get to a point in a story, and Alan Rabbit would come into it. His first appearance was that way, I didn’t know I was going to do a story about Alan Rabbit until he was there on the page.

Do you use characters to anchor you?

Yes. And l was starting to write proper stories and to explore these characters.

The obvious paradox about Calculus Cat is that this is someone who watches TV all day, and you don’t watch it at all.

He watched TV all night. He spends his days working, running around the streets with his grin, and then he comes home in the evening to watch TV, and the TV’s been saving up nothing but adverts, which it insists on showing. They have a big row. Calculus is about to smash the TV, then the TV shows one of his favorite programs, and that’s basically the shape of every Calculus Cat story. It wasn’t about television. It was about marriages and partnerships in a way — in a very uncruel sort of way. It was about the way that people live together without really listening to each other and follow their own individual lives inside relationships.

They want something from each other that isn’t provided.

Yes, I suppose so. I’d thought of it more as people wandering around muttering to themselves and expecting the other partner to be listening to them, when in fact the other partner is wandering around doing exactly the same thing.

Calculus also has the structure of a Warner Brothers cartoon, or of Herriman, in that it’s the same story every single strip. Do you like that repetition?

Yes, it’s a good structure to work from. It means that you can get off onto fresh territory fairly quickly, with dialogue, because the scene’s already set, then the dialogue leads to wacky things happening in the pictures, and things come together and become funny.

There are some scenes of really hideous turmoil, lodged in what’s basically a funny strip. Why?

Because life ain’t easy! Because that’s what happens in cartoons. A comic strip that’s all talking heads is a waste of a comic strip, you could do it with photographs. If you’re drawing the stuff, you should be drawing things that are worth drawing.

Is there any particular reason why you’ve never watched TV? It seems like you’re resisting your whole culture.

Yes, I know. It seems like that to me as well. I really stopped watching TV regularly when I was about 14 or 15 when I was still at home because I was spending more and more time up in my bedroom, drawing, painting, playing the guitar, playing with my girlfriend. And I didn’t want to spend time downstairs with my dad. It went from there. When I came to art college here in Birmingham, students didn’t have TVs. You used to maybe know one person in your year who had a TV, and if Monty Python was on you’d go round and watch it. But otherwise, we couldn’t afford it. That’s the way life was.

It must have been quite useful in a way because it kept you with your own imagination, instead of the popular one.

And now when I see TV most of the time I’m stultifying bored by it. It just seems like such a waste of time. When the TV’s on in a room, I can’t keep my eyes off the bloody screen, and I hate it because of that. If I’m sitting watching it, after five minutes I can think of something I’d rather be doing. It hurts my eyes as well. If I do settle down to watch a film, one film’s all I can watch, and my eyes are jumping around by the end. It’s the same with computers and computer games. I just can’t be bothered with them. I have an initial mild interest to see what the graphics are like, but so far as playing them, it’s an absolute waste of time. It doesn’t interest me in the slightest.

So, your mind and body are completely unadapted to …

… to the cathode ray tube, yeah.

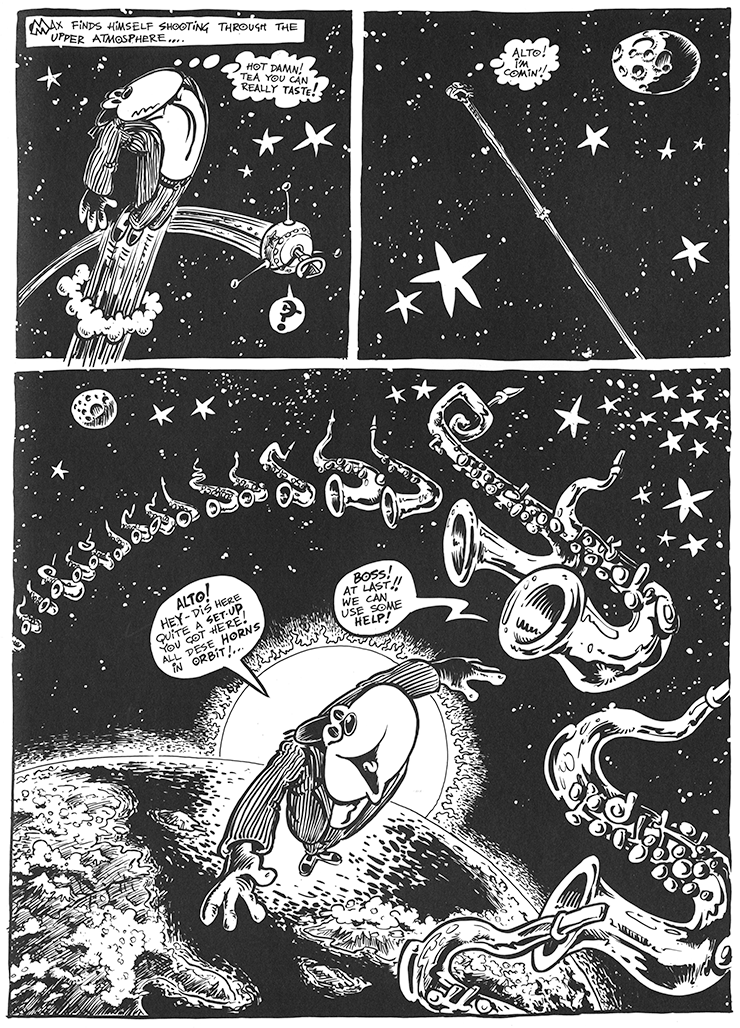

I know Max Zillion came from your friend Bridget playing the saxophone, but there must be more to it than that. His environment seems much mere formed than anything you’d done before.

I think you’re right. I’ve noticed that because I’ve been doing a few more Max Zillion stories just recently because we’re republishing that book with some new pages. It’s interesting because, as you say, it’s a very rounded world. I’m not quite sure how and why. It’s just one that came together nicely, and naturally. There were set positions for the characters. If there was a musician, then there was going to be an agent, and perhaps a club owner, and perhaps a girl singer, and it’s quite easy to fit these in, and to write around them. Then there was the idea of drawing the music, and the saxophone being the brains of the outfit, and being the one that gets him out of trouble. All you’ve got to do then is find the trouble to put him into, and let the saxophone think its way out.

You’ve got bop talk and noir scenes, but it doesn’t seem like pastiche. It seems like something sealed, in its own world.

I deliberately didn’t get stuck in the bebop thing; I didn’t want to keep it in the 1950s. l can put in whatever musical references I need. If he needs to play with synthesizers, then he can. I had an idea once of having him play with James Brown’s Famous Flames and I could have done that because he doesn’t have to be a jazz saxophone player. He can do a tour with James Brown, no problem. There’s no reason why he shouldn’t go and play in a bar in Mexico, or why there should be any explanation for that. So consequently, it is a nice, enclosed world. It’s quite a big world, but everything slots in, and you don’t have to set things up every time you want to introduce a new element.

It’s true that you draw music. You’ve got notes leaping, panels turning cubist, bodies leaping. Do you get some of that energy as you’re drawing?

Yeah. I don’t see how else it would work. I like to make gestural marks, big fast things, and then work them up into something more complicated.

But the initial energy has to be there?

Yeah. Make it bounce. You get the bounce from an extension of the handwriting effect.

The four pages in Jazz Funnies that obviously stand out from everything else you’ve ever done are the scenes at the end of “Hell on Earth.” Why did you draw them?

Because of the story. Because Knockabout was doing a “Hell On Earth” comic, and that’s the way the story came out. When I came to draw them, it was obvious I was going to need more room than a standard page size, so I drew them twice as big. So, they became big projects, and very intense because of that.

Were the things on each of those pages the four worst things you could think of — animal abuse, pollution racism, and social iniquity? Did you have to put some sort of limit on the thing1 that outraged you to get the work done?

I can’t remember. I had four pages to do.