The writer-artist (or artist-writer) is a problematic figure for many reasons. A hybrid figure in either medium, literature or drawing, he or she is suspect. The literary world, for its part, often displays an almost aniconic idolatry in its repudiation of image in favor of language; while the visual world, compelled to reject figurative renderings as mere “illustration” in its promulgation of the extremes of abstraction, often dismisses out of hand the writer-artist, who actually dares to combine figurative images with the additional blasphemy of the written word. But whether they are called pictorial writings, as they were by Austin Osman Spare, or American hieroglyphics, as they were by Vachel Lindsay, or Illuminated Books or stereoscopic printing, as they were by William Blake, the time has come for us to finally recognize it as cartooning and be done with it, and allow the cartoonist to assume a proper place in literary and artistic history.2

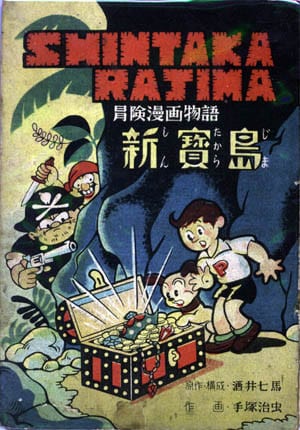

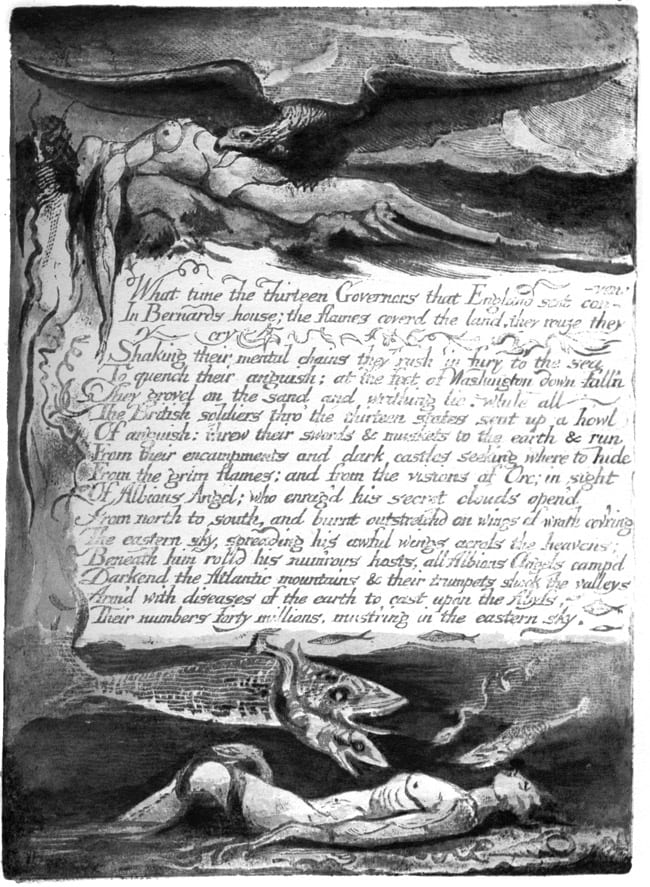

Although surely not the first writer-artist (after all, Egyptian hieroglyphics, Asian pictograms, medieval illuminations and woodcut broadsides preceded him in this), William Blake (1757-1827) is still perhaps the foremost exemplar of this tradition, and, despite his tacit acceptance by the literary establishment, is still a problematic figure. Like many of the writer-artists we will consider, he is quite typical in this regard. For scholar Milton Klonsky, for example, William Blake is “huge and anomalous”: “How to define and where to assign Blake, in what genre or tradition, still perplexes critics,” Klonsky writes, Blake somehow remaining “outside any circle of reference we attempt to draw him into, existing in an epicycle apart and his own.” Describing William Blake as an early comic-book artist/writer, however, might be a good place to start (Klonsky perceptively describes Blake’s works as “a kind of metaphysical science fiction.”3) Scholar Mark Schorer likewise emphasizes Blake’s hybrid status, calling him a “poet of strangest mixtures,”4 whose “gift was a high degree of visual imagination.”5 As editor David V. Erdman observes, “No English poet has had such absolute control over the formal appearance of his own work” as Blake did, and “few have had such ill fortune with their work’s subsequent publication”6 — mostly at the hands of purely literary editors, who often reproduced his works sans illustrations.

As Jean Hagstrum perceptively notes, Blake was a “composite artist” [italics Hagstrum’s], who “drew upon no graphic artist who was not intellectually or verbally oriented.”7 Despite the fact that Blake “‘intertwined’ painting and poetry so closely that they cannot well be separated,” Hagstrum observes elsewhere, literary students of Blake often tend to ignore “the visual side of Blake either because they regard it hostilely — ‘a medium’s scribble’ — or because it seems intrusive or irrelevant.”8 Even Hagstrum, however, misses the obvious comparison (i.e., with comics) — concluding that Blake “was more than a poet who happened to also be a painter. He molded the sister arts, as they have never been before or since, into a single body, and breathed into it the breath of life.”9 [Emphasis mine.] Such a determination, of course, keeps Blake unique — but it also unfairly disinherits Blake’s descendants.

Biographer Peter Ackroyd, for his part, does not miss the obvious comparison — although he mentions it only to dismiss it:

A contemporary comparison [with Blake] might be made with the modern comics devoted to ‘science fantasy’ and genre fiction in general — the Gothic element persists there in the illustrations of gigantic villains and superhuman heroes, all of them placed in abstract landscapes not unlike those of Blake himself. And when in Ahania he piles on the Gothic effects — ‘Hopeless! abhorrd! a death shadow, / Unseen, unbodied, unknown’ — we are close to the overwrought language of contemporary fantasy with its death stars and dark forces. Of course, it would be unwise to press the comparison too far, since there is a qualitative difference between Blake’s illuminated books and the comics of the late 20th century. But there is a resemblance, at least, which springs in part from the sense of alienation or exclusion from the conventional literary establishment that many writers of fantasy experience; modern writers of fantasy tend also to be political radicals with an urban sensibility not untouched by an interest in the occult. They might be seen then, as sharing part of Blake’s consciousness. But before we ask what is so 20th-century about Blake, we might consider what remains 18th-century about ourselves.10

The resemblance is far more than one of mere consciousness, however — but also one of medium. And — as Ackroyd himself elsewhere observes — for Blake, medium and message were one. “Blake had invented a method that allowed him to deploy the full range of his genius for painting, poetry and engraving,” Ackroyd writes, “combining these several arts” to create “a wholly new kind of art that proclaimed the unity of human vision.”11 [Emphasis mine.] Naturally, it would not do to admit that Blake had merely invented the comic book, or that the English literary establishment has been lauding a mere cartoonist for decades. No, Blake must remain unique — never mind the obvious resemblances of the progeny to their father (however distant they may be.)

Blake could even be described as the first of the small-press comics publishers, and also as the father of the minicomic movement, doing (sometimes with the help of his wife, Catherine) all the “letters, illustrating, printing, and finishing” for all his works, “in color with his own hands ...”12 and later selling them at prices ranging from three shillings for The Book of Thel, to 10s 6d for America, a Prophecy,13 although Blake found few buyers for such esoteric works as Milton, America and Europe.

The notes for this article are located at www.tcj.com/callaghanprotocomics