I really enjoyed The Butchery. Its author, Bastien Vivès, has produced a story about the ups and downs of love, of growing close to another person, that isn’t jaded or overdone. The book allows you to feel what it is communicating, without judgment. And all that’s necessary to do so is this:

- Read the book, in which a young couple lives a select set of quiet, yet crucial moments before their relationship dissipates, or takes another form.

- Ascribe your life experiences to the book and have a few thoughts.

- Walk away and live on.

You just have to absorb and roll with the book’s vignettes — its colored pencils and open page space — where the nameless characters move and intuit. From there, you admit to yourself that you’re feeling some common, core human emotions, and you let that be OK. You don’t have to pretend to be smart. Or hold some incisive take, or remove yourself to act and consume as someone who is above the visceral experience. You can simply read the book and fall toward it. It is about people, after all. It is about something real that we all go through and see. And there’s something nice about that. It’s nice that the author is interested in directly connecting to his reader, and is vulnerable enough to do so. It lets the author and his reader meet on a level playing field, not in the bleacher seats of some try-hard intellectual pissing match. And that is something I can and always will appreciate.

But maybe typing all of this, I just sound pretentious.

I mean, I literally just told you how to read a book. What insight do I actually have?

So, how about this: the author, Vivès, is a French cartoonist. But I don’t have any special point about that. It just feels pertinent to write it. Maybe the observations I’ve shared so far are common to all French comics? I don’t know; you’d have to tell me. But what I do want to say about Vivès is that I think this guy is really good at making comics and telling stories. And with The Butchery, he totally demonstrates his ability to match subject matter with execution, as delivered by his craft. To discuss this, I’ll give one example, and then I’ll get out of your hair.

I really gravitated towards Vivès’s use of the open page and negative space. Take a look:

This is page 16 from the book. It’s part of an entire dance sequence, all of it presented similarly. Here, there aren’t any square panels typical of a comic book page, but the effect is the same. Your eye reads and is guided through a series of sequential images, inherent to a larger picture. But the lack of square comic panels, and their borders and rigidness, sets both characters free, along with their action. In a way, the author’s chosen presentation reinforces how lively these characters and their experiences are. It all feels more organic, like these people can occupy any part of this page they want to. They just have to dance there. And the texture of the colored pencils they’re dressed in lends them looseness and spontaneity.

It also relates to, maybe, how we remember things. Like relationships of any sort, but especially those left behind, you have to recall them, and The Butchery — while not explicitly told in the past tense — does conjure thoughts of memory or ghosts. Plus, there is something about a blank, white page that resembles where inside our minds we might imagine our thoughts to take shape.

It’s that canvas, or whatever cliché you can name. Our thoughts come to us seemingly from nowhere, and that nowhere might as well be an abyss. But we don’t imagine it as so. No. Instead, it’s that blank, white metaphor. And in The Butchery, Vivès strips away what is tired with this trope to refocus it. Instead of it being about a creator taking action, making anything from nothing, Vivès shows that the blank page is just another place where life can happen. It’s a venue. And the dance on page 16 is an example of what can occur there. It begins with both characters glancing out, looking away, and it ends with them locked right on each other. The book is beginning, and so is their relationship. This subtle decision, encapsulated in such a presentation, shows a union taking shape. Like an idea.

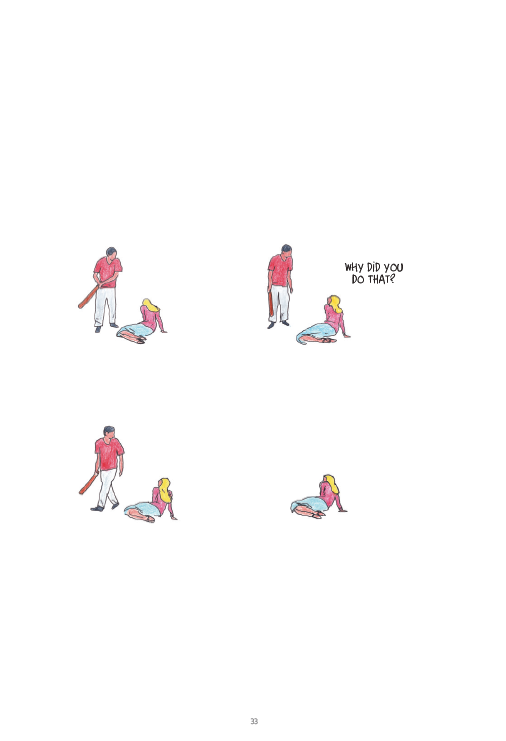

And ideas fizzle. The back half of The Butchery is concerned with loss. A character will walk onto a blank page, just as how they’ll exit. But what do they leave behind? On page 33 (above), it looks like it’s hurt.

There’s a peculiar cynicism inside Vivès’s story, and while it may seem predictable for a book about a relationship to end with a breakup, I don’t believe he treats the conclusion as so. It feels more so inevitable, which implies cynicism. But it’s not bitter. I just think Vivès aims to show us a whole picture. While breakups could very well be inevitable, all the rest of it — the dance, the park walks, the uncertainty of why you care — comes with the experience. And that’s worth something. Just as living a human life is worth something. The ups and downs, all of it, you know? Whether you’re jaded or you’re just cruising through this thing on autopilot, it’s easy to lose the point. But luckily, there’s all sorts of opportunities to get it back. In The Butchery, it is by feeling genuinely, in the space you have to feel it.