While art school narratives such as Daniel Clowes’ & Terry Zwigoff’s Art School Confidential and Walter Scott’s Wendy books are often used to satirize the self-seriousness of burgeoning artists or the pettiness of the art scene, London-based cartoonist and illustrator Clio Isadora’s graphic novel debut, Sour Pickles, grounds her portrayal of the art school experience in the more material concerns of labor and class. Isadora never strays far from these themes, but her directness does not undercut her wit. On the contrary, she delivers an honest and grimly funny depiction of a niche experience that feels not only accessible, but universal.

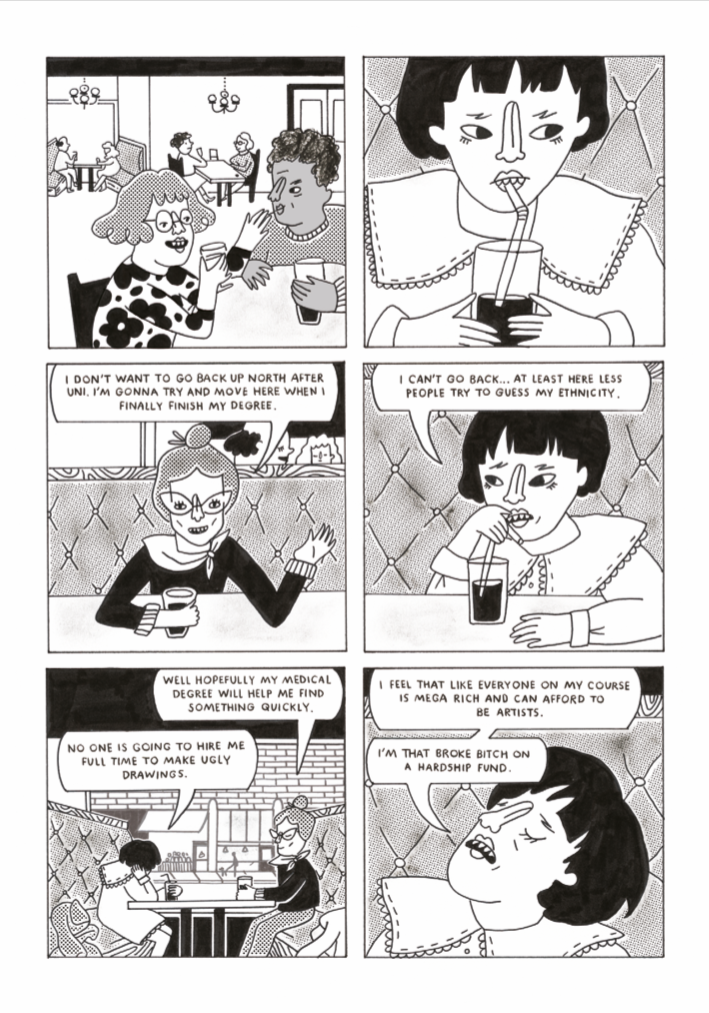

The book follows art student Pickles Yin as she traverses her final year at a prestigious art school. While she seems to have little trouble honing her artistic voice, she has misgivings about how she can use what she learned to get paid after graduating. Without the privilege of connections and familial wealth that many of her peers enjoy, Pickles suspects that her prospects are vanishingly small.

“I feel like everyone on my course is mega rich and can afford to be artists,” Pickles says at the story’s outset. “I’m that broke bitch on a hardship fund.”

With a daunting workload between her and graduation, Pickles, along with her friend and classmate Radish, decides to procure amphetamines from the internet in the hope that the drug will make their efforts easier. Within this loosely plotted framework, Isadora teases out the humorous, the heartbreaking, and the banal.

Sour Pickles reads very much like a debut book and succeeds because of its shaggy assemblage, not in spite of it. Its component pieces vary in length and tone, showing its protagonist in various lights and from various angles in a way that feels real. Pickles is, at turns, a dedicated friend, a put-upon daughter of flaky New Age parents, and a wholly-relatable dumbass. There are emotionally-wrought passages, as when she returns home from school to attend the funeral of a friend who died by suicide. There are also single page gag strips, as when Pickles attempts to cut her split ends, but, succumbing to a fit of speed-fueled hyperfocus, ends up with a ragged coiffure. Still, Isadora delivers tonal consistency in her portrayal of Pickles. Isadora's cartooning is minimal, but conveys volumes. Scenes resolve naturally, and many of them end with Isadora’s depiction of Pickles affecting a shamed, pained grimace. These sidelong glares, bolstered with bold manga-like sweat droplets, are used to convey uncertainties, crises of confidence, and detached fatalism, often simultaneously.

In its presentation, Sour Pickles preserves a thematic continuity with Isadora’s shorter comics, although it’s clear she is pushing into new territory from an illustrative perspective. While she has used risograph print techniques to a great degree (and to great effect) in the past, she does not do so here. Instead, she opts for a blend of tone and starkly contrasted black and white, interspersed with washes and waves of gauzy color. As usual, Isadora demonstrates a great facility for composition, but it is this use of color that is the most distinctive and interesting element of Sour Pickles. She uses the effect sparingly - mostly to depict characters in the euphoric throes of the speed high. To further underscore the ecstasy of these sequences, Isadora depicts Pickles with glimmering shōjo eyes, which evoke an unsettling mixture of hope and disembodiment. In Isadora’s rendering of these scenes, Pickles comes to resemble the stretched, skewed portraits that she creates for her classwork.

Sour Pickles eschews up-by-your-bootstraps moralizing for boot-on-your-neck reality and offers no tidy resolutions. In telling Pickles’ story—based, in part, on Isadora’s own story—she illustrates, with myriad examples, that while talent is important in a creative field, starting out from a position of financial security (with a healthy dose of social capital) is critical. This truth runs counter to the rise and grind narratives of popular culture, but the calculus bears it out more often than not. Although Isadora’s depiction is less than optimistic, she hints at a potential for Pickles to define herself on her own terms, however limited her circumstances may be, beyond the scope of the story. “I don’t want my personality to be a reaction to financial hardships,” Pickle confides to Radish after a post-graduation run in with their well-to-do former classmates. “But you’re rich in spite,” Radish tells her.

Spite is rarely enough, but it’s a good start.