Paranoids plotting the UK's calamitous progress through 2018 and joining the data points with red string spotted a complementary gust of high weirdness in an unexpected quarter, when The Boötes Void kicked off in David Lloyd's digital anthology comic Aces Weekly. Created to "Booda," the not exactly secret pen-name of the very open and voluble Stewart K. Moore, The Boötes Void is authentically absurdist, exuberance and tension wrapped tightly together. Between its echoes of Spike Milligan's The Bed Sitting Room and the arrival in the story of one of Philip K. Dick's pink crystalline intelligences, the whole contraption was a drastic piece of signal jamming entirely consistent with its cultural moment, as the country of the comic's origin clogged up with its own accumulating dysfunction.

Through the good offices of writer Pat Mills, Moore then drew "The Divisor," a 12-part Defoe story for 2000 AD possibly marking the final appearance of the strip's 17th Century zombie hunter and certainly staging a drastic incursion of idiosyncratic style into a comic which doesn't rock the artistic boat very often. This story too involved space missions, the British and the Dutch being locked in a Restoration-era Space Race to the Moon aboard glass spaceships with interiors modeled after the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. But the narrative only held on to the swirling art by its fingernails, Moore having added Bernie Wrightson to a palette of influences alongside Al Feldstein and Jack Davis, with a hint of Al Columbia to season. Again the art juggles drastic expansion and compression, crazed cannibals devouring the Dutch Prime Minister down on Earth while the Biblical Chariots of Ezekiel sail through the heavens, piloted by luminous beings resembling descendants of that old Weather Report album cover by Jack Trompetter. Characters look up in terror or down in rage, and if Moore has one core artistic knack it might be for catching the looks on faces of power and faces of powerlessness. Not coincidentally, he contributed one of the wildest covers 2000 AD has yet had, marking the UK's COVID lock down in April 2020. A wraparound image shows the Justice Department fumigating the contaminated Mega-City One at street level, while Judge Dredd himself appears only as a broken leviathan, a partial face ballooned on a vast public address screen, harshly authoritarian and comically desperate.

All this time Moore was also talking about his own long-gestating graphic novel, and Project MK-Ultra: Sex, Drugs & the CIA Vol. 1 is it, or the first half of it. The book is adapted from an unproduced film screenplay by Brandon Beckner and Scott Sampila, which might raise legitimate queries about exactly how much of the plot's pacing and viewpoints were laid down in outline before Moore filled in the spaces; but in any case the artist has grabbed the project by the scruff of the neck.

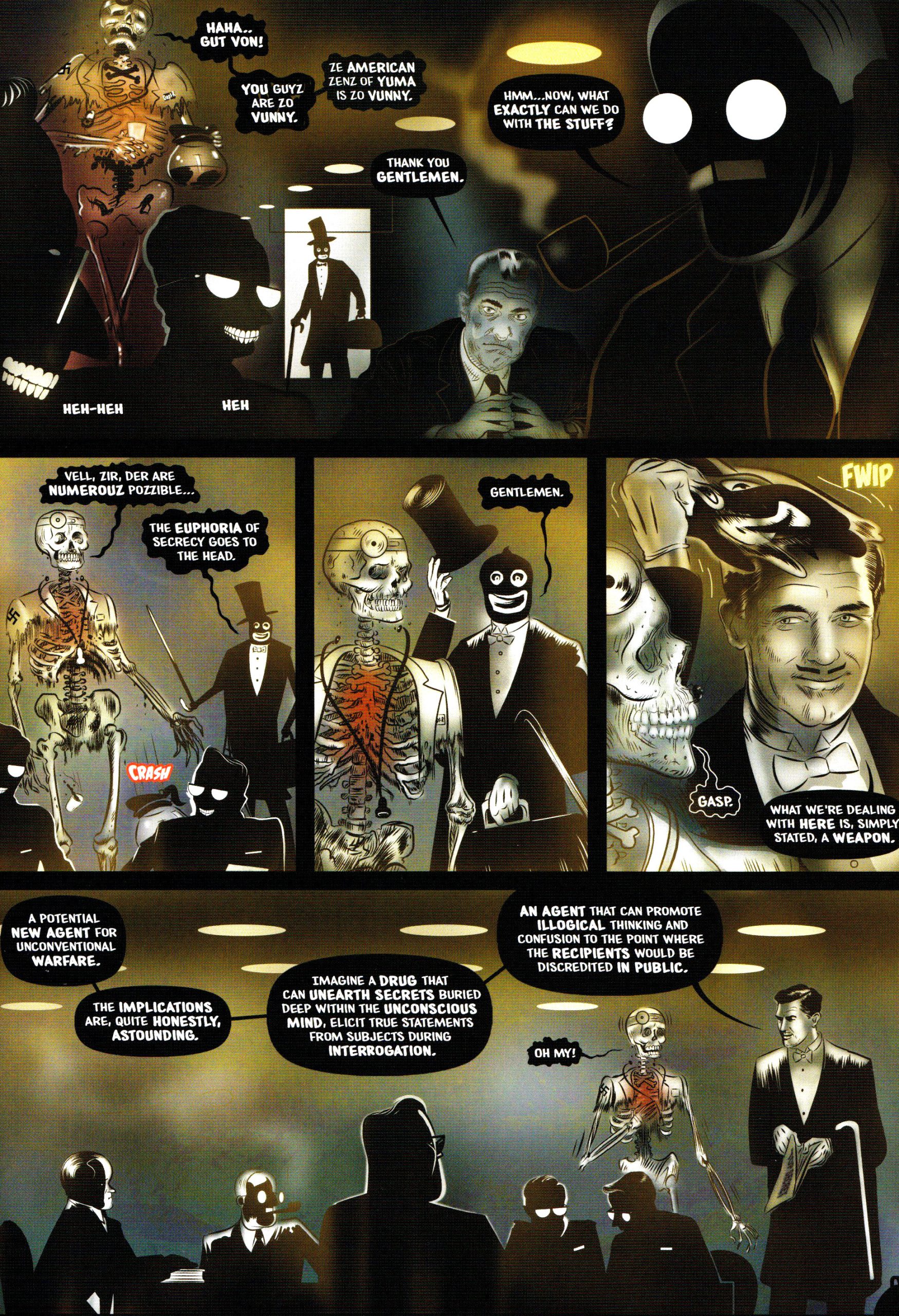

MK-Ultra, as anyone with a stock of red string already knows, was the program started clandestinely by the US intelligence community in the early 1950s to see whether human thought and behavior could be modified using a bunch of far-out and also illegal mind control techniques, most relevantly here the forcible dosing of unwitting rubes with LSD, in the hope the drug would make a subject cough up all their secrets. The book's plot, which does undeniably have the arc of a movie pitch, involves San Francisco journalist Seymour Phillips stumbling across breadcrumbs of the conspiracy in 1970, and encountering a deeply eccentric, highly paranoid and possibly psychotic former spook named Chase, who claims to have been one of the group of young gung ho G-Men who enthusiastically trampled over citizens' human rights in the name of the program decades before. A lot of the book is either Chase telling his story to Seymour, with various phantasms and reality distortions crowding in on the scene, or flashbacks to those early days of MK-Ultra, with Chase and his buddies carrying on like spoiled children, government-spawned clones of amoral brutality.

This theater of cruelty gives Moore plenty of room to rave. Once more the focus sways from micro to macro and back, from full pages of swirling chromatic chaos and grotesque hallucinations, down to delicate character touches, as when individual strands of an unhappy woman's hair cut across the pool of spotted black making up her shadowed face, a whole mood summoned from four strokes of the thinnest digital brush in the palette. Unreliable narrators navigate the psychedelic territory, and a fog of cartoonish unreality builds up, possibly more than some readers will care for. A projected film record of a key strategy meeting, presented in the story as recorded truth, nonetheless has a former Nazi doctor drawn as a walking skeleton, a memento mori from the darkest past. George Hunter White, the man running MK-Ultra's bordello-based outreach Operation Midnight Climax, is drawn as a smooth bald giant, a morphing baby-man who also pops up in incongruous Navy dress blues. When two characters discuss the story's primary villain while sat in a diner, a version of their nemesis prances past on the street outside, seen by no one but the reader; he glances out of the page, forming yet another conspiracy of just you and him. This cartoonishness, the constant plasticity of all the figures even when not tripping, isn't mockery of something serious but a drastic exercise in mood, in a comic of atmosphere and altered states rather than linear plots.

This is also a book about LSD. It begins with Bicycle Day, chemist Albert Hofmann's ingestion of LSD in April 1943, rendered by Moore as the full monochrome James Whale Universal Pictures theme park experience; Hofmann's lab is all expressionist angles and swathes of shadow while a gothic storm batters the windows. Hofmann's trip blasts the book from black and white into color, and like all the other ones in the book is teeth-rattlingly weird. Alternative artistic viewpoints on LSD are available; and since Moore specifically starts with Hofmann's ride into the unknown, one obvious counterpoint is Brian Blomerth's Bicycle Day, which has an extended version of the same event in a very different register. Blomerth's steadily paced sliding diorama and locked perspective on his canine characters makes it seem that the light shows and visions that dazzle Hofmann are summoned up from inside himself; but Moore's trippers are being drastically imposed upon from somewhere outside, some hidden power barging in, and the perspectives lurch wildly. Blomerth, backed up by his book's introduction from Dennis McKenna, shows an accidental encounter with one of the universe's forces of light, while Moore has got something Lovecraftian poking its tentacles around the door, weaponized by a government of brutes.

Project MK-Ultra is set in a paranoid time and has been published in another one. The ties between the two eras—between 1970s bummers about environmental damage and covert surveillance and foreign conflict exhaustion and a political class of yahoos, and the 2020s versions of all the same things—are hard to unsee once you have them pinned up and joined together with string. The book has something to say about those ties too, about things flying apart in a great cultural centrifuge that now seems to be spinning at full pelt again. It's another piece of culture jamming from an artist with the right skill set for the operation, one in a position to embody the maxim that might have been said by a few of the book's political villains, but isn't: your order is meaningless, my chaos is significant.