O wonder!

How many graphic novels are there here!

How beauteous comic art is! O brave new world,

That has such works in't.

— Adapted from William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act V, Scene I, ll. 203–206

* * *

This book proves it. The 2020s have much in common with the 1930s. I found this out when I explored screwball comics and discovered they peaked in the 1930s. Back then, women’s constitutional right to vote was just over 10 years old and they would not be able to get legal abortions anywhere in the United States for about another 40 years. In between fighting two world wars, and a plague, the economy collapsed and business people jumped off buildings in despair. Others sat on flagpoles or danced in marathons that went on for days. People went a little nuts and this was reflected in popular culture. Surreal, manic nonsense strips like Nize Baby (Milt Gross), The Squirrel Cage (Gene Ahern) and Smokey Stover (Bill Holman) provided much-needed laughs in the graveyard night. Nearly a century later, the potency of non-ironic, absurdist humor has returned. One wonders why that could be. I guess I don’t believe in a sanity clause, after all.

In the long-ago and oddly familiar era of the 1930s, novelist Aldous Huxley cast his imagination far into the future, extrapolating the relatively new developments of genetics and social engineering into a horrifically bland world. In a time of great instability, Huxley created a vision of a perfectly stable world, but—instead of being a comfort—it was an alarm. Since its 1932 publication, Brave New World has regularly appeared on shortlists of the best novels of the 20th century. One can see the book as a wry Switftian satire, or a grim and decidedly unfunny cautionary tale instrumental in showing how science fiction as a literary genre could be relevant and vital. I think it’s all of that and more. After all, it was written by the author of The Doors of Perception, an early bible of the '60s drug culture (and the inspiration for a rock band’s name).

I groaned when I picked up Fred Fordham’s new graphic novel adaptation of Huxley’s celebrated novel, just released from HarperCollins in standard issue full-color hardcover. You know it’s a graphic novel because it says so on the cover. I saw Fordham had previously adapted Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird into graphic novel form (I have not read it), which suggested the creation of this book could be driven more by commerce and less by an original artistic vision. Flipping through the pages, I saw slick graphics with digital lettering and coloring: an all-too familiar template for the kind of emptiness I have come to associate with the majority of modern commercial comic books released from book publishers who seem clueless about what is original and valuable in comic art. But, even so, I started reading. And I’ll be damned, because it’s good. Quite good.

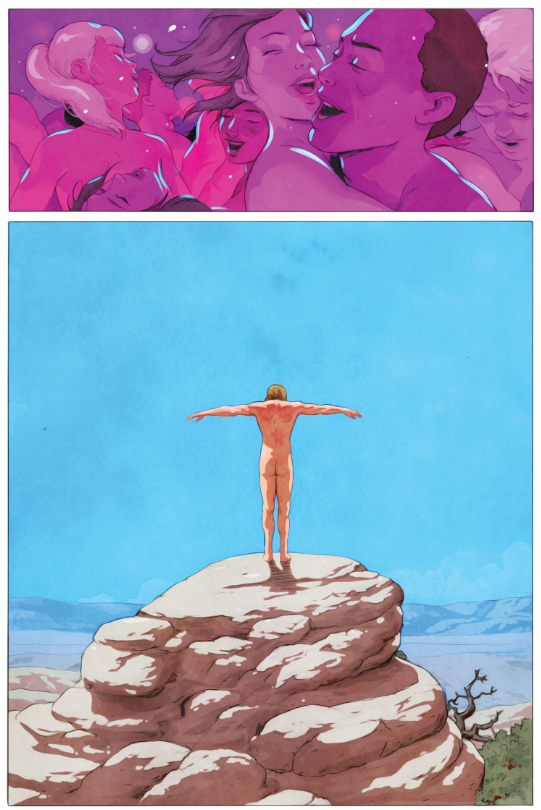

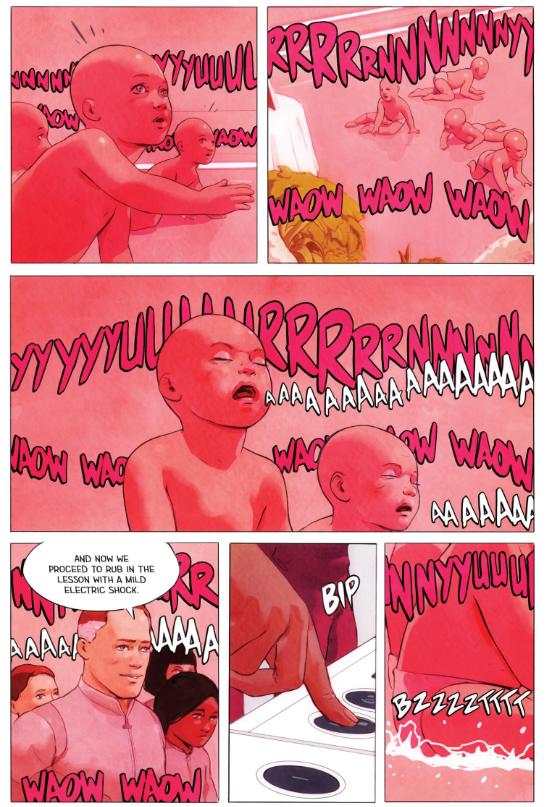

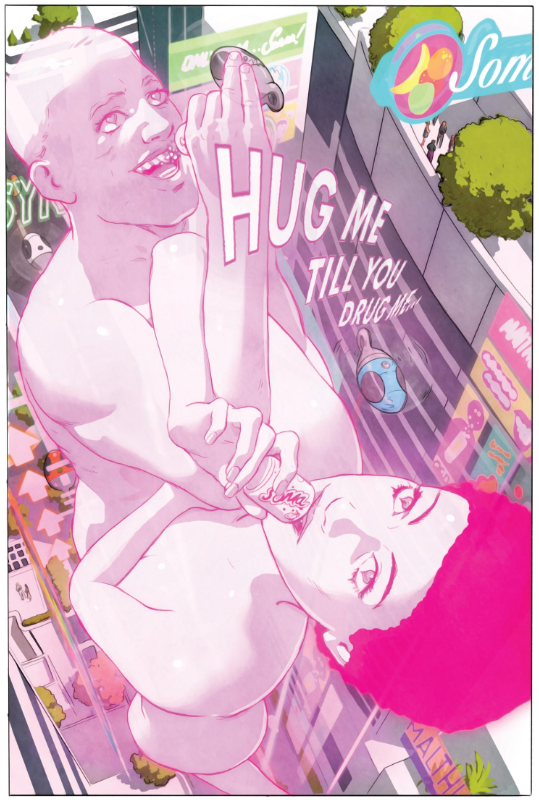

Fordham has created a version that seems true to the spirit of the original—at least, as far as I can tell. It has been 40 years since I read Brave New World. I vividly remember certain parts: the genetic manipulation of humanity; the feelies (holographic movies that connect to all the senses); and soma—the euphoric drug that everyone constantly uses as they screw each other’s brains out. Or nearly everyone. Our protagonist, Bernard Marx (not to be mistaken for a Marx brother), a brooding, intelligent, sensitive man (his class is genetically made to be that way) has begun to sense the stifling mediocrity of his world. That part I had forgotten. I remembered some of the world, but the actual story long ago faded from my mind.

This smart graphic adaptation is fully in service to Huxley’s story—and what a story it turns out to be, with sex, adventure, violence, love, tragedy, and vibrant characters woven into a philosophical treatise on God and the meaning of life with Shakespeare thrown in for good measure. Fordham does a great job slicing (or should I say splicing?), dicing, and breaking down the action. His characters, as depicted visually, have depth.

This smart graphic adaptation is fully in service to Huxley’s story—and what a story it turns out to be, with sex, adventure, violence, love, tragedy, and vibrant characters woven into a philosophical treatise on God and the meaning of life with Shakespeare thrown in for good measure. Fordham does a great job slicing (or should I say splicing?), dicing, and breaking down the action. His characters, as depicted visually, have depth.

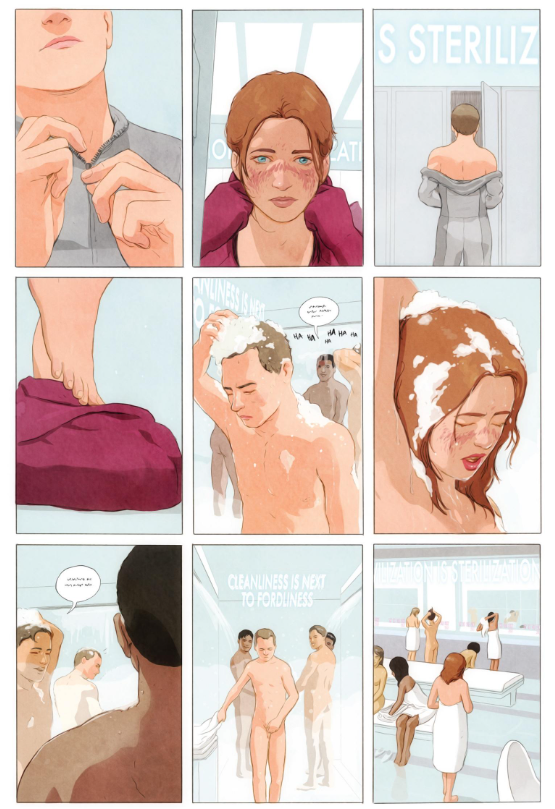

Best of all, like Will Elder sticking in background “chicken fat” gags into Harvey Kurtzman’s rigidly laid-out MAD comics, Fordham puts his own creativity into the designs of the clothing, objects, and architecture of this antiseptic vision of the future. Sleekness abounds. Reading Fordham’s book, I got an HBO Westworld vibe and was reminded of Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s brilliantly-designed adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Android Dream of Electric Sheep? Gigantic, distracting advertising and propaganda messages are projected everywhere in the world (see also H.G. Wells’s The Shape of Things to Come, published in 1933—one year after Brave New World). It is a place of sensory overload. But, where Dick and Scott imagined a future society in which the masses live (Fritz Lang/Metropolis, Gotham City-style) in technological rubble, the Huxley dystopia is squeaky clean and OCD-level orderly (Huxley’s symbol was the Ford assembly line—to the point where Henry Ford is worshipped as a deity in the world, although his name also appears to sometimes be a swearing substitute for “fuck”). Huxley’s future as decanted by Fordham to modernist ideas of dirty future worlds is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water to the seedy bar down the street. That’s the point. Everyone has a life of happiness and good health, the perception of prosperity, “unrestricted copulation” and prolonged youthfulness... until they hit 60, at which point they get hit in the face with Robert Crumb’s cyanide pie.

A cursory review of the Wiki entry for Brave New World tells me there is more in the novel that appears to be left out of the graphic version, such as the “Malthusian belts” (contraceptive devices) worn by women. Or perhaps Fordham has drawn them and I missed it–there is a lot of detail in the graphics. This explains to me why the book’s least successful scene, the party with the Arch-Community-Songster falls flat for me–some of the underpinning is either not included or too subtle for me to grok.

Graphically, the art evokes a tiny bit of Jaime Hernandez and Mike Allred, particularly in the design of the main female character, the red-haired, freckle-faced Lenina Crowne who reminds me a little of young Maggie and Joe (Madman/Frank Einstein’s girlfriend). The pronounced coloring of Lenina’s freckles, which look almost like a large facial birthmark in the shape of wings, or a roughly symmetrical Rorschach blot, is visually striking, but I’m not sure what meaning—if any—the detail has within the story. I need to renew my acquaintance with the original text; perhaps the connection is simply in the character’s description (perhaps Fordham is referencing the psycho-hero Rorschach in Watchmen, another dystopian work in the lineage that traces back to Huxley).

Fordham’s deceptively mild pastel color palette, his clean line work and precise—almost robotic—depiction of forms moving through panelized space and time all contribute to the atmosphere and horror of Huxley’s story. It is a masterful treatment that works on several different levels all at once. And, it is uncomfortably familiar. Marijuana is soma, Netflix shows are almost feelies, and well... take a look around at the recent backsliding of abortion laws in the United States to find further parallels. The story in this book is easy to get into, and it works like a narcotic—just as Huxley’s novel does–and yet it is about the very numbing, the very banishment of rough edges that its craftsmanship delivers. And yet, here I am: writing a blandly positive review of a derivative, instead of celebrating an original. Oh shit. We’re Forded.