On January 22nd, the longtime Spanish alternative comics publisher La Cúpula announced on social media that the cartoonist Martí Riera Ferrer, the vast majority of whose work they had published since 1979, had died of cancer.

This was the second time that his death had been announced by the same publisher: a four-page prank notice of his death by suicide in 1982, conceived of and assembled by Martí himself, was one of many ways that the Spanish underground’s flagship magazine El Víbora kept its readership off-balance, demanding attention by any means necessary, in the early years of its existence.

The late '70s and early '80s were a fervid time in Spanish comics, a period referred to by critics and theorists as the “boom del cómic adulto,” in which the national comics scene, which had been heavily censored and sanitized under the Franco regime, very suddenly grew up. Martí (who signed all his work using only a mononym, a longstanding tradition in Spanish comics) was at the center of this ferment, alongside peers like Max (Francesc Capdevila), Miguel Gallardo, Nazario Luque, Juanjo Mediavilla and Javier Mariscal. Save for Mariscal, all of them appeared in the first issue of El Víbora, and Mariscal included, all of them would publish there throughout the 1980s, helping to make it one of the most vital organs of alternative comics in the world, easily the equal of Métal hurlant, RAW or Garo.

Martí was born in Barcelona in 1955, and grew up reading the same alternately knockabout and sanctimonious tebeos (children’s comics) that the rest of his generation did. He was raised a faithful Catholic in childhood, and dreamed of being a missionary, but in his teenage years he became enamored by the hippie lifestyle, and a period in Amsterdam inspired him to pursue the graphic arts. His comics and illustration work began appearing in Barcelona’s underground comics press as early as 1973, often in a highly rendered style that wore a close study of EC, especially as filtered through the American underground, on its sleeve.

But it was in 1979 that he finally settled on the style which would serve him for much of his later career, with a story in Star, a rock-and-comics predecessor magazine to El Víbora. “Monstruos Modernos” (Modern Monsters) adopted a bold, thick-lined black & white style with a clear debt to Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy to tell a nasty little story about a criminal reprobate who hates the elderly, and so invades the home of an old woman, where he beats her, ties her up and finally sexually assaults and murders her just as the police arrive, escaping with his life in the final two panels.

The influence of the popular (if critically despised) cine quinqui genre of Spanish films about delinquents (not unlike the sexually-charged U.S. “roughies” of the '60s and '70s) was notable on all of his generation of Spanish cartoonists, but Martí’s willingness to depict the weight—not just the shock—of violence left him, curiously, an isolated figure, a queasily ironic moralist within the “just lines on paper” playground of id that characterized the late underground and early alternative comics scene. Not that Martí didn’t play his violence just as much for laughs as any other irreverent alt-cartoonist, but his severe style and refusal to look away made the laughs cut deeper; you don’t get a Martí strip out of your head even days after you’ve read it.

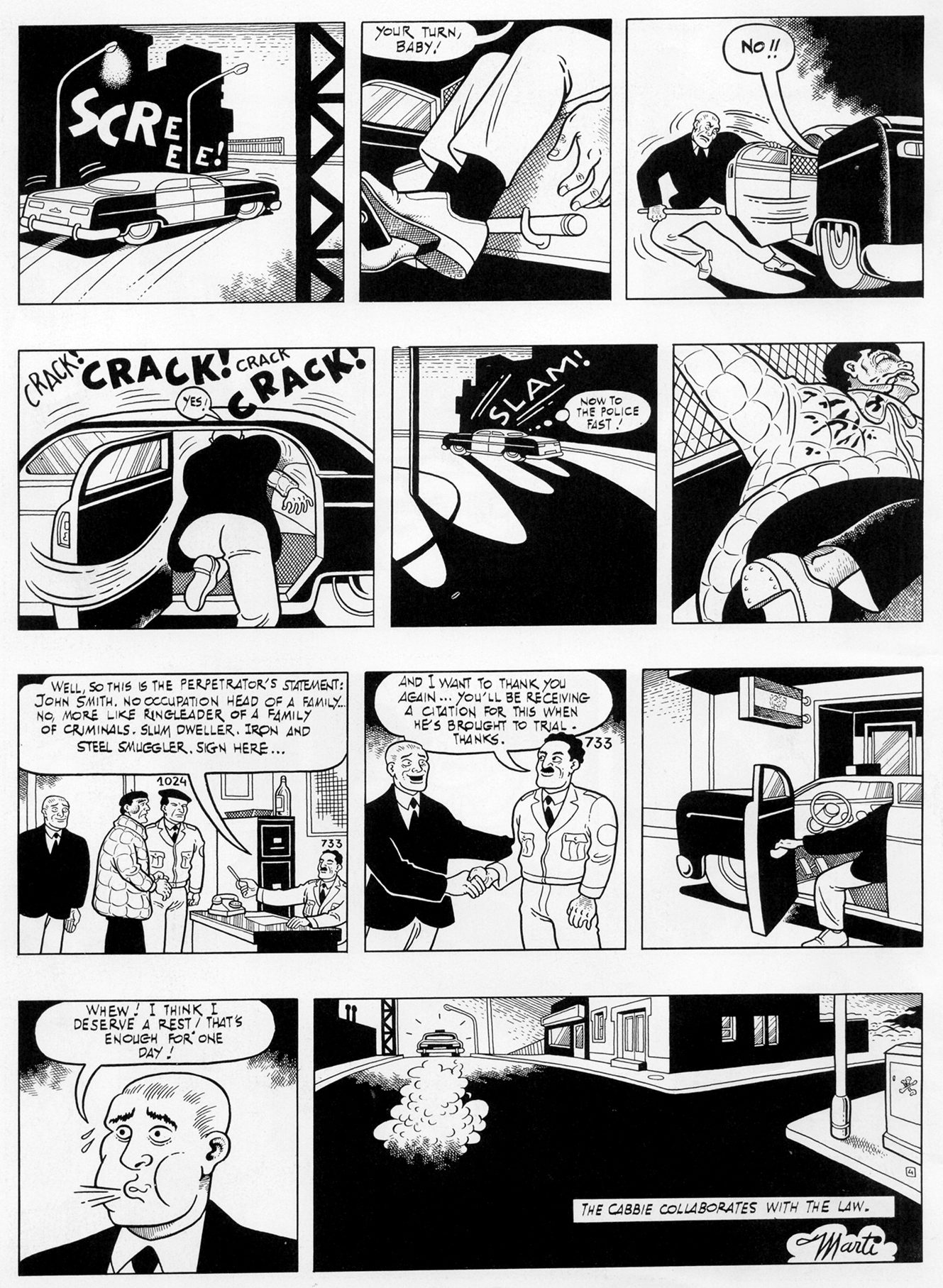

His most famous series, Taxista (published as The Cabbie in English), began as a sarcastic Spanish riff on Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, reimagining Travis Bickle as a starry-eyed, Franco-admiring blonde agent of order who “collaborates with the law.” As the yarn grew in subsequent installments, however, the sarcasm congealed into a more thoroughgoing irony, as Taxista (the name everyone, including his family, calls him) Cuatroplazas became by turns more pathetic and more effective than Bickle ever could in a single movie. By the end of the second volume (collected in 1991, presently unavailable in English), Martí seemed to have grown tired of his most well-known character, perhaps due to readers who missed the irony and just wanted a Spanish edition of Watchmen’s Rorschach; despite an 11-page preview of a notional third volume he drew for the short-lived anthology La Cruda in the 2000s, included in La Cúpula's comprehensive Taxista: Edición Definitiva in 2023, Cuatroplazas was a product of the 1980s and could not survive long past it.

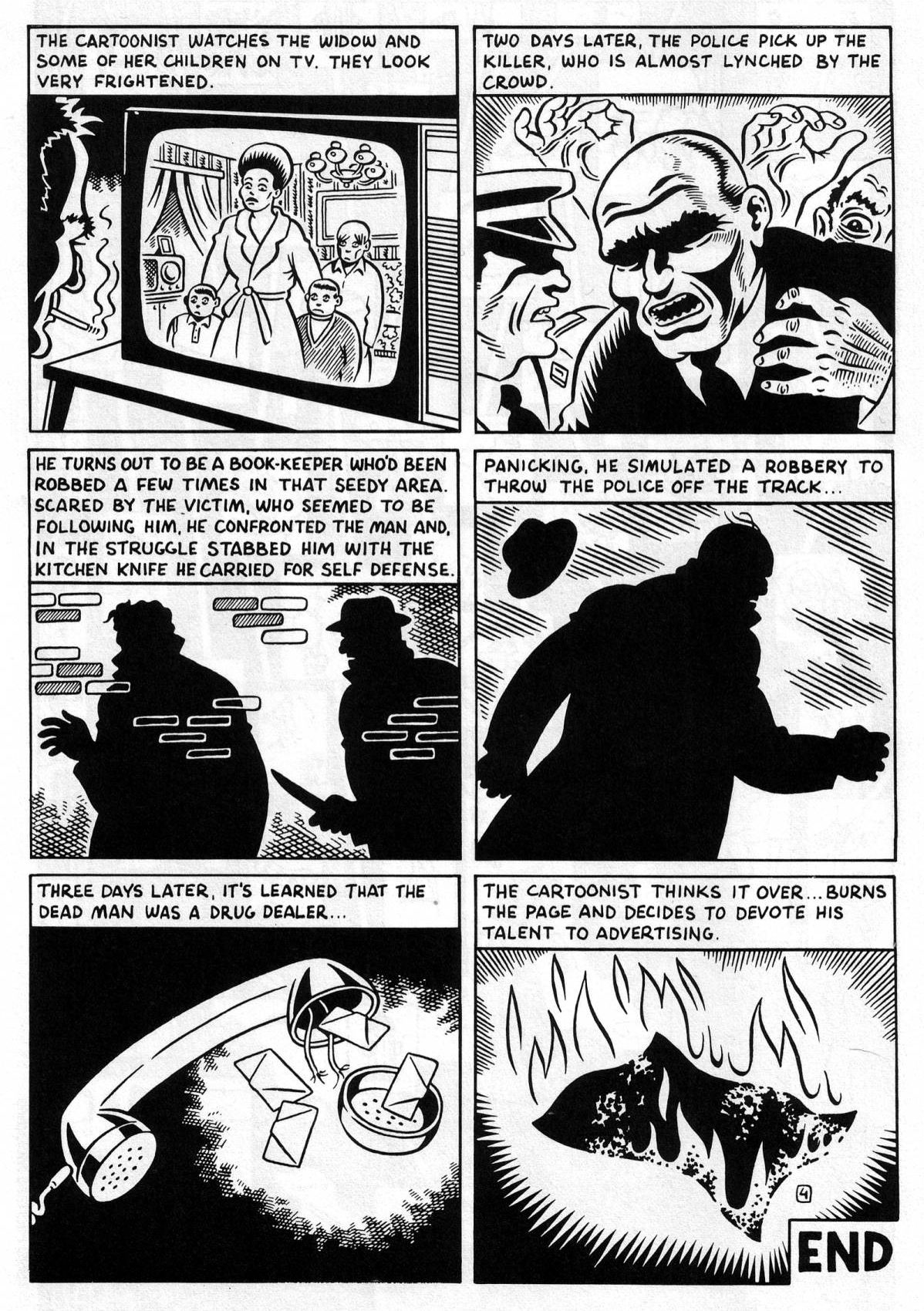

But by page count, Taxista was a minor portion of Martí's 1980s output anyway. The vast bulk of his material, and where his economy of narrative and line really shone, was in short stories. Whether grisly and mordant, severe and strangely poetic, or wildly experimental with line, shape and color, his short fiction contained some of the best and most rewarding comics published anywhere in the world in the 1980s, and the fact that only a few sporadic stories ever made it into English (highlights include “Reality” in RAW Vol. 2 #2, “Repulsion” in RAW Vol. 2 #3, and “Barcelona!” in Drawn and Quarterly Vol. 1 #9) is one more piece of evidence, if any were needed, that the English-language comics sphere at large has no idea how to value European comics generally or Spanish comics specifically.

In 1993, after having drawn four book-length serials (Contra los N.A.D.A., Taxista 1 and 2, and Dr. Vértigo) and 50 or so short stories since 1979, Martí took something of a sabbatical from comics. Always a private person and rarely interviewed, he gave no reasons for walking away, but he was far from alone: the Spanish comics market had been in freefall, and venues for publication were thin on the ground. Even the redoubtable El Víbora only survived the '90s by leaning into outright pornography. A return in 2000 with the bande dessinée-formatted Calvario Hills, published first in his old colleague Max’s magazine Nosotros somos los muertos and later in La Cruda, sparked a brief renaissance: Martí placed two more baroquely sardonic stories in El Víbora before its 2005 shuttering, and contributed more occasionally to anthologies thereafter, apparently content to have become an éminence grise as a new generation of Spanish cartoonists, both inspired by and revolting against the example of the '80s boom, took the stage.

Of the five initial El Víbora cartoonists, Mediavilla soon became only an occasional artist, more frequently penning scripts (especially for Gallardo) in a highly satirical mode. Nazario established himself as Spain’s second-greatest chronicler of the queer imaginary after Pedro Almodóvar, both with his trans detective character Anarcoma and in a series of lush stand-alone stories and portraits that pulsated with ecstatic blasphemy; aside from retrospective collections, he's left comics behind for fine art. Gallardo worked more steadily and fecundly than any of them, exploring a wide range of styles and moods, toward the end of his life turning to collaborative autobiography with his autistic daughter; he passed away in 2022. Max remains a singular icon of cartoon invention and simplicity, one of the world’s most philosophically stimulating cartoonists and impossible to predict from year to year. Meanwhile, Martí’s long silence had always seemed to his devoted readers like a pregnant pause, as though one day he would return with another magisterial collection à la Taxista, to deepen and interrogate the themes of his work that run down to the present day.

A supreme ironist about topics like right wing violence, abortion and Islamic terrorism (his 1986 story “Terrorista,” about a Libyan suicide bomber in the cause of Palestinian liberation, remains surprisingly relevant today), surely he could have had so much more to say. But then, as he demonstrated on the final page of “Reality” (first published as “Lo Real” in El Víbora #100, March 1988), the real world is far too disorganized and inconvenient for the uses of fiction. In the era of online discourse, irony is an unreliable tool, and perhaps silence came to seem preferable to being misunderstood, whether deliberately or otherwise.

At this point it seems likely that the he-man Gouldisms of Taxista will be his most lasting legacy, but his final book-length work, Dr. Vértigo, which was awarded Best Album at the 1990 Barcelona International Comic Fair, deserves to be better known. An extended meditation on Martí’s signature theme of chaos vs. order, it plays out not on the mean streets of the Barcelona underworld but in the phantasmagoric psychosexual mental landscape of a woman being treated by two competing psychiatrists, and is as ruthless in its heavily ironized depictions of the cruelties of medical patriarchy as Taxista is in its heavily ironized depictions of the cruelties of justice.

Taken as a whole, indeed, Martí’s work can be understood as a scathing attack on the oppressive patriarchal values he grew up with. If it can also be read as a sneaking reification of those values, well, we can all only escape our own histories so far.