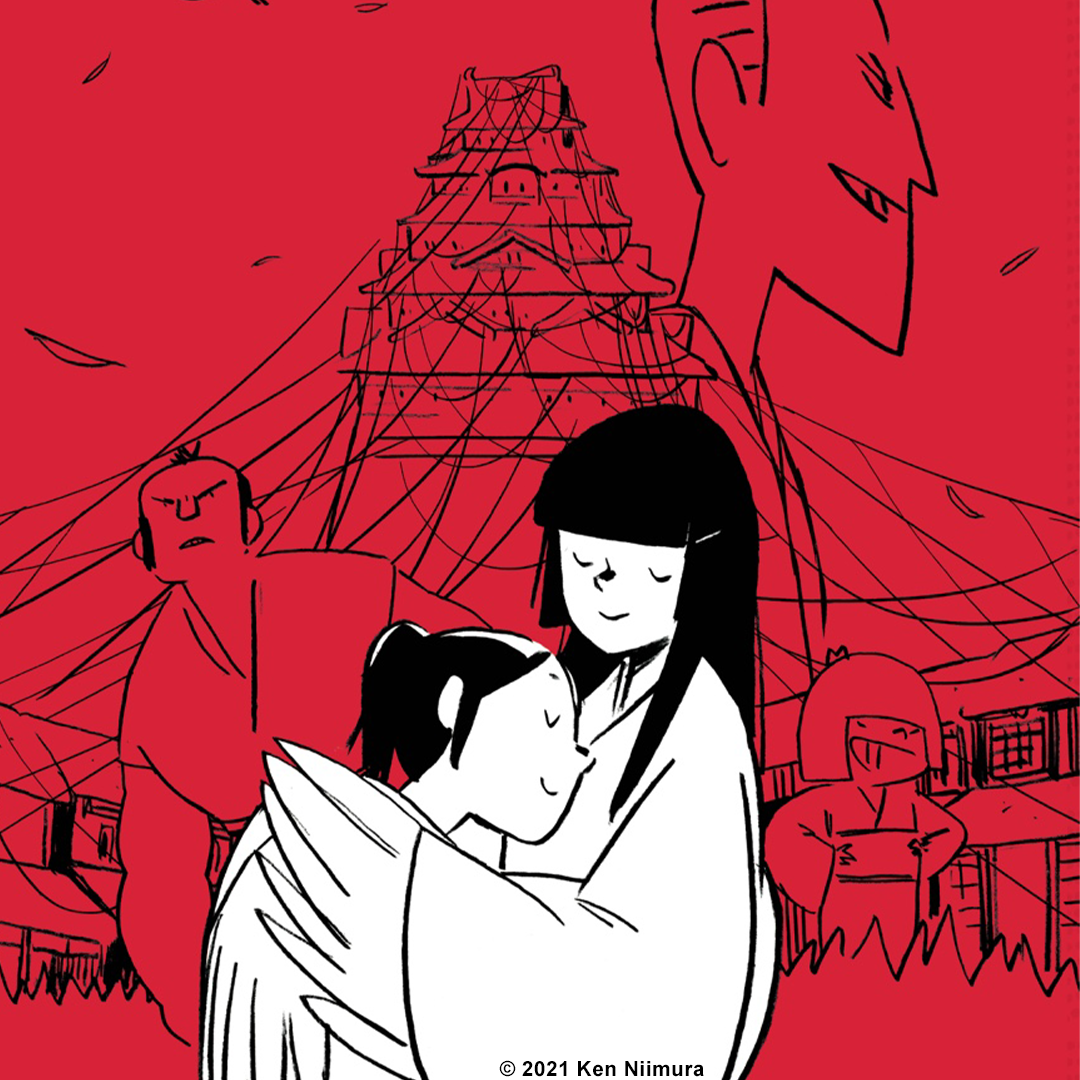

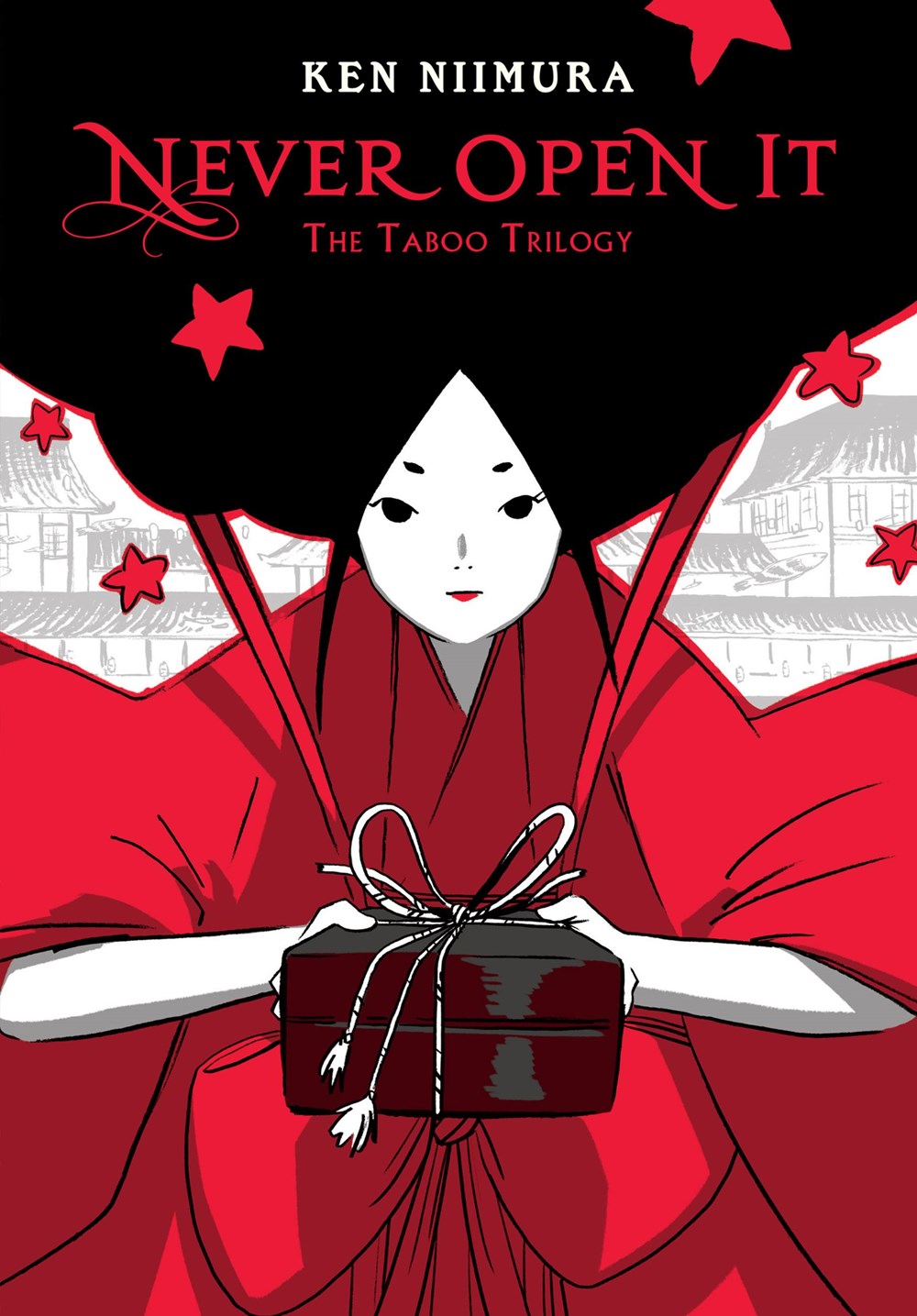

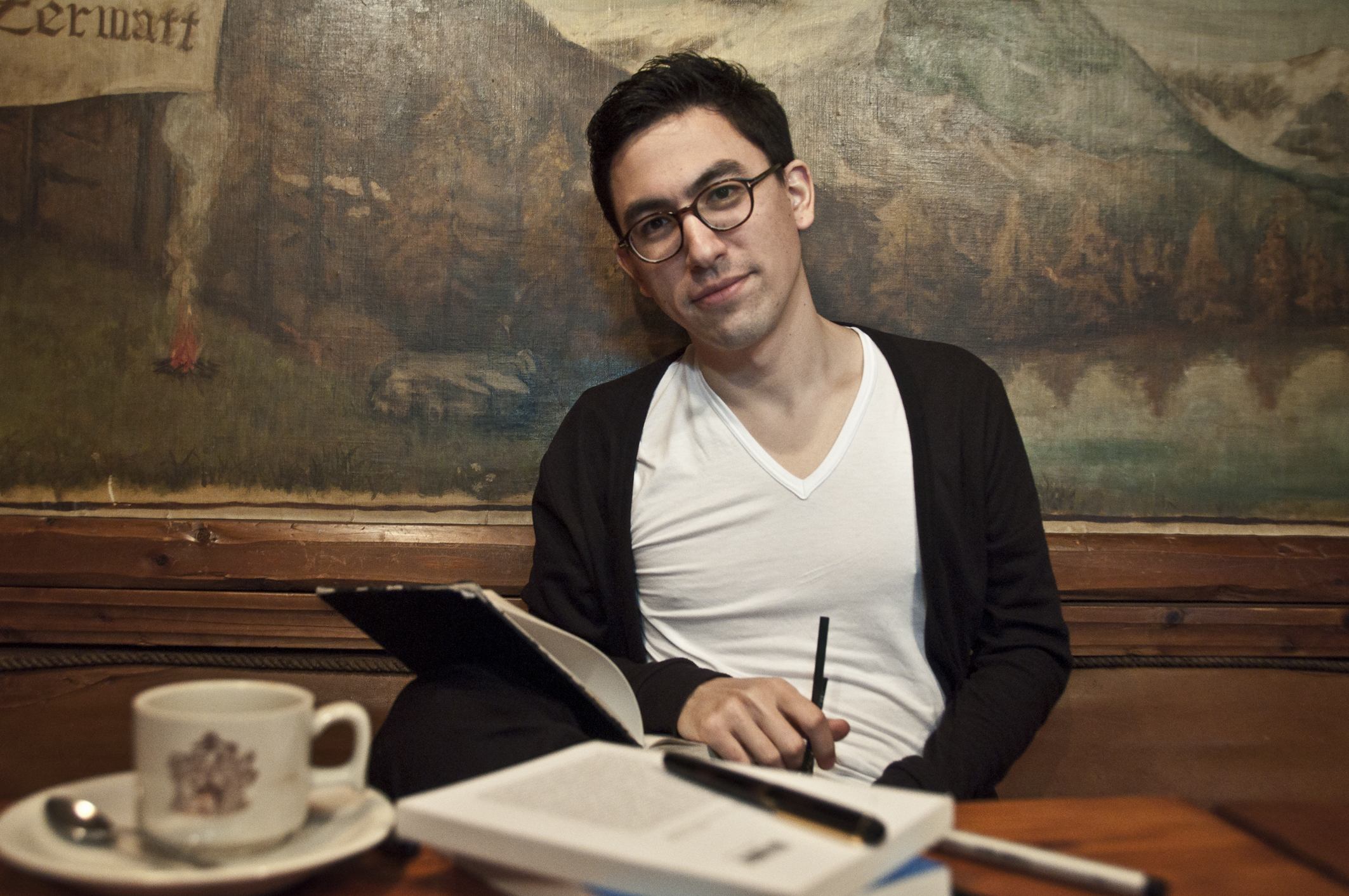

It wasn’t his first comic, but most comics readers were introduced to the work of Ken Niimura in the pages of 2008's I Kill Giants. In the years since then Niimura has made Henshin, a collection of short comics, and the ongoing series Umami, which he publishes online through Panel Syndicate. His new book Never Open It: The Taboo Trilogy, which was published by Yen Press in late 2021, retells three Japanese legends. It’s a departure from his other work. The pages are sparse, the pacing more deliberate. It’s the work of an artist, who as Niimura tells it, rethought their process and approach for this project. The pages can be as light and funny as anything he’s ever made, but can also be hauntingly beautiful, the work of an artist who has been working for many years and is his most impressive book to date. We spoke in late 2021 over video chat after a long day for him and at the beginning of the day for me about how his process is not economical, language, and the universality of these stories.

It wasn’t his first comic, but most comics readers were introduced to the work of Ken Niimura in the pages of 2008's I Kill Giants. In the years since then Niimura has made Henshin, a collection of short comics, and the ongoing series Umami, which he publishes online through Panel Syndicate. His new book Never Open It: The Taboo Trilogy, which was published by Yen Press in late 2021, retells three Japanese legends. It’s a departure from his other work. The pages are sparse, the pacing more deliberate. It’s the work of an artist, who as Niimura tells it, rethought their process and approach for this project. The pages can be as light and funny as anything he’s ever made, but can also be hauntingly beautiful, the work of an artist who has been working for many years and is his most impressive book to date. We spoke in late 2021 over video chat after a long day for him and at the beginning of the day for me about how his process is not economical, language, and the universality of these stories.

* * *

As far as the three stories in this book, when did you first encounter them?

I’ve known them since I was a kid. There’s a category of folk tales here in Japan known as “Mukashi Banashi”, some of which are pretty recurring and well known. My parents would read them to me, and I’d also find some of them in manga and animes, where certain episodes are taken straight out from these folk tales. I started working on the book about four years ago, feeling that even as an adult, there were a number of things in these tales that felt weird, so I tried to see if I could figure out what I felt didn’t work, and tried to fix it. Which leads to the book you have read.

Making a new story is different from retelling a story, because it becomes very consciously about how you tell the story.

You’re right, however, in the case of Never Open It, I started working on straight adaptations of these tales at first. I attended a children’s book workshop here in Japan, run by American illustrator Steven Guarnaccia, where the challenge was to bring an idea and try to make what they call a picture book dummy (a sample). I brought the first legend in the book (“Urashima Taro”) and I made a children’s book out of it. The original story ends when the kid goes back home and he finds out hundreds of years have passed, and that his parents have been long dead. He then opens a box and catches up all the years he passed away from home, becoming an old man. End. That’s it. [laughs] I always thought, even as a kid, that it was such a cruel story. And I didn’t even get the sense of the story either. So as I was trying to make the children book, there was something in me that was like, I don’t agree with this ending, I cannot show children this ending. I ended up making an ending where the kid didn’t open the box and so that at least he didn’t become an old man. I showed that project to a couple of children’s book publishers here in Japan and they were like, we like the idea, and we agree with the idea behind, but we cannot show children this alternate version because it’s different from the traditional tale. So I thought, if this can’t be a children’s book, then maybe it can be a comic, and that’s when I developed the first version of “Never Open It”. And it felt good in the sense that it was great to be able to claim the story back for the characters. The purpose of those folk tales is probably passing a message, so the story makes sense when you think of it in terms of like a storyteller saying: I’m going to pass along a message. However, when you think of it from the point of view of the characters involved, it can be very cruel. [laughs] You’re sacrificing somebody to tell to pass on a message. I wanted to see if there was a way to rethink the story from the point of view of the characters. If characters had the freedom to act differently, what would change? That’s what led to the first draft of the short story “Never Open It”, which I self published here in Japan. Then I felt there were other stories that play with the same concept of the taboo, and that’s when I started working on the folk tale “The Crane Wife”. And once again, I got to the end of the original, which in that case is that the main character opens the door to a room where his wife’s threading a cloth, discovers that she’s actually is a crane, and she flies away. The end. I rewrote the whole ending imagining if there was something else going on behind those shut doors.

Then I worked on the middle story, “Empty”. At that point I wasn’t sure if it was going to be three individual books or would be part of a series or one single volume. At the very end the solution was that I was trying to make something very overly complicated for the last story, and I realized that in many forms of theater, such as kabuki, there’s often times a piece of kabuki, which is a serious story, followed by a comical interlude of like fifteen minutes, and then another long serious story, and I thought: maybe this is what I need.

So you always saw them as connected or related in some way even if you weren’t thinking, this will be one book.

Yeah. To be honest there are just so many folk tales out there, that for a while I was playing with a combination of different ones, like a puzzle. Seeing what would happen if I added this story or used this other one. In the end it naturally became this book about the idea of taboo or interdiction, but it could have taken many other shapes.

Calling them “The Taboo Trilogy” as you did implies that these stories have a moral or a lesson to them.

The things is, some of these folk tales are 800 or 900 years old. They contain an idea, a concept, that has maybe been of use for people back in the day, but I was thinking, are these lessons valid anymore? Do we need them as they were? So in that sense, this book is more of a question than an answer, and I’m not sure what I actually ended up saying. [laughs]

Adults tell many stories to children and one of the messages is often, you can’t always trust adults. Which is funny, but that message underlies so many of these stories.

What I like about these stories, especially in the case of these Japanese folk tales, is that they’re pretty open ended. They can be interpreted in many different ways. For example, there’s what’s considered to be the standard version of “The Crane Wife”, but there are actually different versions depending on the region, the era, with many differences to the characters, the ending, etc... There’s for instance a theater play version by Junji Kinoshita that was also turned into an opera, and it’s the same skeleton, you could say, but the way he takes it, the moral lessons behind it, are quite different. There’s also a completely different approach in a movie called Crane, by Kon Ichikawa, where again it’s taking the same ingredients with a different twist. That’s what’s so much fun about playing with them, that they’re pretty open ended and you can take them in many different directions. Compared to other legends from other countries that are a little more concise, the Japanese ones are pretty vague. That has to do with the language, too. Japanese is sometimes very vague, for good and bad. Sometimes people reply and you don’t necessarily know if they’re saying yes or no by just listening to the words. Then the context does the rest, of course. But that’s in a way how vague Japanese can be. So maybe the language has influenced the way the stories are told here, or maybe this is actually part of the way Japanese culture expresses itself, by being vague, but that’s in a way the beauty of it, I think. Meaning one thing and the opposite at the same time. [laughs] I’m not too knowledgeable though, but these stories were part of an oral tradition, until one point someone finally wrote them down, leading to some changes to the stories. It’s like playing a cover of a known song, you can take it in so many different directions.

Every culture has these stories of, here’s what you’re supposed to do, don’t be curious. When someone is curious, bad things happen. Which I’ve always hated.

As a kid that’s exactly something that I didn’t agree with – and as adult either. You could say, in the bigger scheme of things, that these characters were able to run away from their supposed “fate” just by rethinking what was happening around them. I think that reconsidering why things are the way they are, can lead to better solutions. These things have maybe been kept in a specific way for centuries, but unless I understand why they’re that way – or why they shouldn’t be another way – then they’re not going to be of any use for me at the present time. I think it’s good to question and reconsider things.

There’s a universality to all of those stories, but they’re also very culturally specific.

Another option for me could have been taking for example the myth of Pandora’s Box or there are a couple episodes from The Bible that play with this theme. I could have taken stories from different cultures that had that common message, and the book would have worked too. Being a comics nerd though, these Japanese legends lend themselves to some very nice looking scenes. [laughs] My mom’s Spanish and I grew up in Spain and I was raised listening to Spanish legends too. There are good ones, but visually they don’t have the same punch.

The pages are beautiful. And it felt like there was an element of play in trying to find the right approach to drawing them.

Thank you! There’s been a lot of trial and error. If you compare it to other comics I’ve done in the past, this one is more minimalist in terms of the art. I wanted to find something that would make sense, in terms of the rhythm and the specific experience of turning the pages and so on, thinking more of a graphic novel approach rather than something episodic where I would be bound to tell specific amount of information in 22 pages. There are people like Chris Ware, that I really love because I think he approaches his comics not in terms of what’s on the page, but rather more about thinking about the way readers are going to imagine it in their heads. That’s why the rhythm in his comics is so on point, why they feel so alive. It goes the same for many mangas. So for Never Open It, my approach was to put on paper the minimum necessary information that would make it understandable enough for people to imagine what I have in my head. It was more about taking a step back as an artist and not trying to make super flashy pages. Sometimes – for example I’ve worked sometimes doing superhero comics – where you’re being paid by the page, and you have the pressure of, I have to put this much money on paper somehow. [laughs] It has to look good enough to justify the page rate I’m being paid. Which I get. That leads to so many gorgeous and marvelous comics, but this one time I went, what if I don’t need to make gorgeous images, but rather useful images to be read?

I don’t think I’ve talked about this before, but I did a first version of the whole book of Never Open It, turned everything into jpegs as double page spreads, and I did a new cut of the whole comic. Thinking about how it would read, or how the rhythm could be in an ideal world,: which panels would I take, which panels would I add, which scenes would I add, where would I place the specific panel beat on the right side or the left side for the reveal or not. It was a nightmare because as you know, compared to text or if you take a line that doesn’t really affect the book much, but if you take one panel out of a comic, then you have quite a problem there. And I had a BIG problem! If you look at the original art, some pages are exactly the same way as they are in the book, but some pages have been modified and made out of different pages and panels. I changed the order of certain scenes. I wrote new scenes. It’s not a very practical way of working because it just adds so many problems. I think that took me two months full time just doing that. But I feel – or I hope – that people will start at page 1 and don’t stop reading until the end. If that’s the case, mission accomplished.

Wow. That is intense. And I think the results speak for themselves, but that’s a lot of work.

I promised myself I would never do that again. And I just finished a book... where I did it again. [laughs] I’ve drawn everything, good, and then I was like, if I had the chance to go back in time, what would I change? And I rewrote and redrew all that I wanted to change. It’s a painstaking work, but the final version reads so much better! I still draw manually and then scan and retouch. If I did everything digitally, maybe that would be less of a mess and it would be faster, but I guess the luxury of not having a deadline is where I can make this exactly the way I envision it. Graphic novels allow for that.

It’s a joy and a luxury to be able to be able to work without a deadline like that and just focus on the story in that way.

It’s a luxury, because it doesn’t forcefully make sense economically. I started working on Never Open It without a contract, so I took as much time as I needed. One thing I love about making comics is that it’s not as expensive as making games, or movies, so ultimately as long as I can earn a living through illustration or other comics, it’s doable. I did it the first draft of the first story during a workshop. The same for “The Crane Wife”. I was focused on the process and just taking the whole experience as a chance to learn more about writing, learn more about Japanese folk tales, learn more about writing and editing. So I’ve been very lucky to be able to finish it. And even more to find a publisher interested in putting it out too!

People who know you for Umami or I Kill Giants will see that stylistically this is a very different book and feels very different in ways that were clearly intentional.

I Kill Giants is almost twelve years old now right now, so yes, I’m a different artist now. The book I was mentioning before, is a new book with Joe Kelly. This time though, the way we’ve worked has been different than when we did I Kill Giants, and the results – graphically, storytelling-wise and content-wise – are so much more mature. But I did feel that when we started working on it, I was in a different place as a creator than twelve years ago, as far as how much I know about the craft. I think it’s kind of shaming in a way that I’m forty and maybe now – maybe – I’ve reached a point where I’ve started getting an idea of what comics are about and how to make them good.

On the one hand, the great thing about making comics is that if you want to make one, all you need is a piece of paper and a pencil. There’s a beauty in the sense that most of any type of creation – be it fashion or a movie, or anything – starts by doodling, writing down an idea, so the initial tools are often the same for everyone: a pencil and paper. And as comics creators, we’re lucky enough to be able to stay with those same tools and keep playing with them. They’re very simple tools. However from that point on it’s a totally different story [laughs] I didn’t know when I started making comics how complex it is to make them. We are supposed to be writers, and editors, and artists and designers, and prop designers, and costume designers, and character designers, and graphic designers, all in one. And for example, the way I play with storytelling and its inner rhythm has for me more to do with music than anything else. You have to draw from so many different fields, and in theory you should be good enough or proficient in all those things to make one single good comic book. That’s why it’s only now that I’m at the very beginning of feeling comfortable enough to approach a comic without panicking about all that there’s to do, and just allow myself to focus on what I want to tell. So hopefully it starts from here. This is such a terrible sales pitch! [laughs] But as a creator this is honestly where I think I am.

Reading Henshin and Umami and other work of yours, you always seem to be very consciously playing with the form with trying new approaches, adjusting your style.

That’s exactly the case when I did Henshin. That was the first job I did in Japan and that was a challenge for me for because I’d done I Kill Giants and other comics in the States and in Europe, but as an artist I wanted to try everything to write myself too. And so I approached it like cooks approach market cuisine, where you go to the market and see what is in season and fresh and just cook something good with it. That’s Henshin for me. It was my first time actually living in Japan, learning and seeing new things every day, and I’m just going to try to use them as ingredients to tell something. It was a little bit like playing jazz in the sense that I didn’t know what the end result was going to be like. Whatever I lived in that one year period of time, that was what I put on paper. But that was also a way of playing, not knowing where these ingredients would take me.

From that idea of going to market and cooking, came Umami, which is really a story about creativity. Should you be more rational or creative? Should you be bound by rules or not? That was the beginning of that story. I think that in the stories I’ve written myself there’s always been that playful element which I really enjoy. Whenever you’re confronting the unknown, that’s scary but it’s fun.

Did making these short stories help you to think differently about style and how you want to work?

Absolutely. In Japan for most manga-kas before committing to a long story, they’ll work on short stories, and get an idea of what works and what doesn’t by playing with different stories. When I started working in comics in Spain, I worked on many very short stories. Then I did I Kill Giants, which was a big leap for me at the time, because I’d never done something that long. Then because I wasn’t that comfortable writing, I decided to come to Japan. I knew that in Japan, artists work along with editors, that help the artist almost like a script doctor, a role which we don’t have that much in the states or in Europe. So I realized that if I really wanted to learn how to write, I thought I would benefit from having an editor. Even when you’re good at it, I think its very useful having one. Working on the short stories in Henshin allowed me to try different things, keep the things that worked in them, and rethink the ones that I thought could be done better.

The good thing about the graphic novel format is that it’s pretty freeing. I Kill Giants was published as a comic book series, I’ve done stuff for Marvel, some short stories in the French album format, I’ve serialized in Japan. I’ve basically worked in the three biggest markets there are to comics, and all of that has allowed me to understand what feels the most natural to me.

There’s a quirk to comics. A movie has the same format regardless of where it comes from. Be it a Japanese movie, an American movie, or a European movie, you can always screen it in a movie theater or show it on TV and you’re fine. But comics, because they developed differently depending on the market, you end up with huge French albums, tiny Japanese tankobons, and the American comic book. And while they’re all variations on the same idea, the reading experience – the pacing and the rhythm and the way things are shown in a comic – is dramatically different. Compare Tintin to Dragonball. However, in that sense, we’re lucky that we have that much range compared to, for example, movies. And that’s why I feel really comfortable with the end result of Never Open It: as an object, as a storytelling device, I feel like all the short stories I’ve worked on in the past have allowed me to get here.

As you were saying that I kept thinking how comics, like a lot of these stories we’ve been talking about, have something so universal about them, but there’s something very culturally specific about the telling.

That’s something I always think about a lot. For example, Henshin was originally serialized on the website of the Japanese magazine Ikki, not in the magazine itself. I knew that friends of mine from abroad who don’t read Japanese would be going to look at them, so even though they would not understand what the stories are about, I made them so that they would be visually fun to look at. The original stories in Never Open It are Japanese. I wrote the first draft of the children book in Japanese, but I wrote the comic version in Spanish because I feel more comfortable with it. Then I translated all the drafts into Japanese and English – I wanted to have Japanese editors I know and friends reading them and give me their take. That allowed me to have the point of view of people that were already acquainted with the legends, and know how the new version made them feel, and but also that of those that were reading them for the first time, as it was the case of some American friends who didn’t know the stories. I combined both notes, to know that this part of the story is not working for these people, but this doesn’t work for this other kind of readers, and I tried to make something that would work for both of them. I like comics for comics readers, because I’m one myself, but whenever I make stories I try to make them as accessible as I can because I really want all kind of people reading them. In terms of age, culture, regardless of how used they are to reading comics. That’s just how I approach things: I grew up between Spain and Japan and between two cultures and two languages. I think I’ve grown used to making sure that all kinds of people understand what I try to say. I think that’s second nature for me.