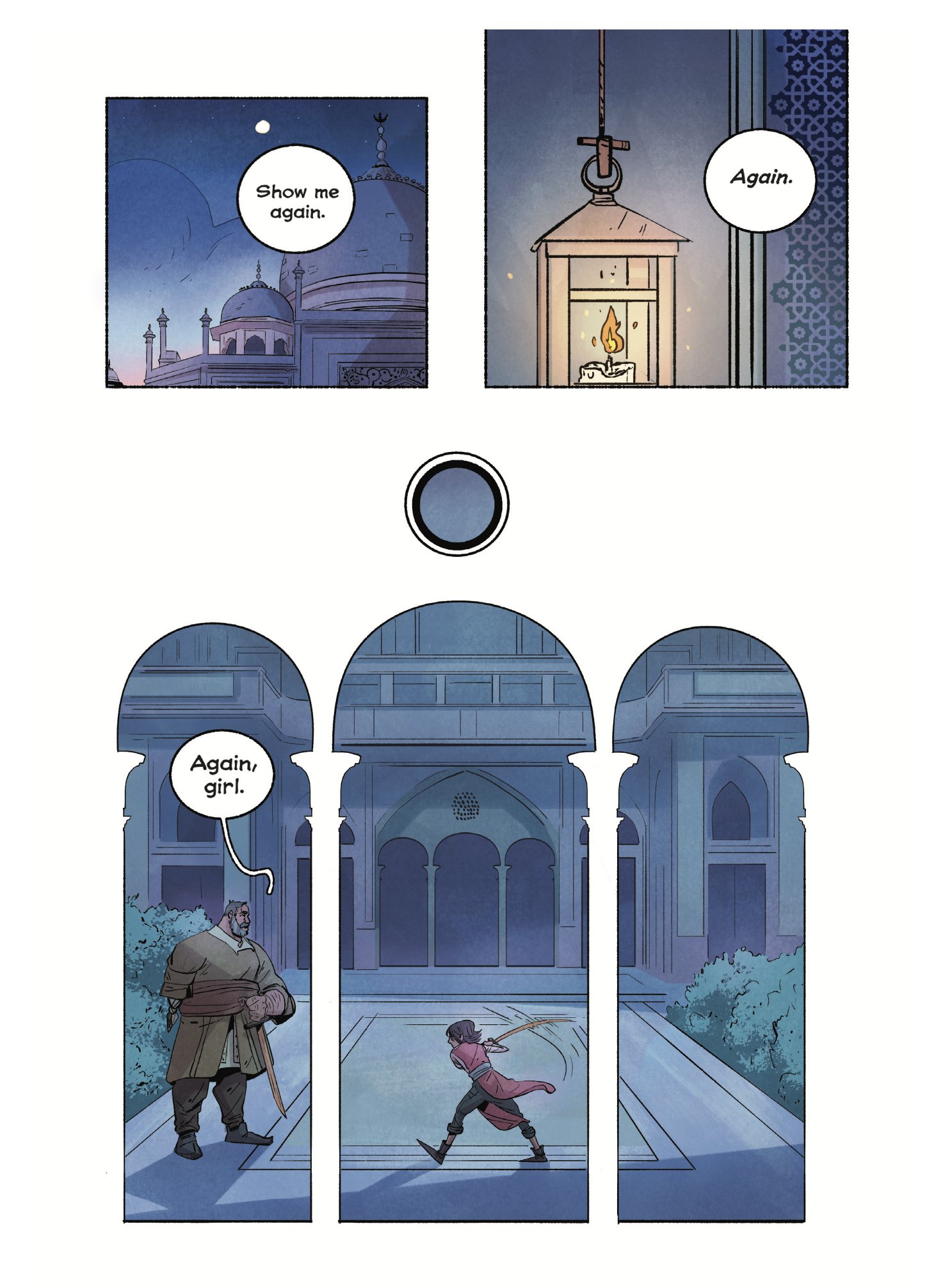

Squire tells the story of a teenager named Aiza training to be a squire with dreams of becoming a knight just like the ones in the stories she loves. Along the way, she makes new friends, learns about the realities of the military, and starts to question the truth behind the stories that she loves so much. This interview with artist Sara Alfageeh and writer Nadia Shammas touches on their shared backgrounds, how they designed a fantasy world that draws from this one, and the role of storytelling when it comes to empire building.

Squire tells the story of a teenager named Aiza training to be a squire with dreams of becoming a knight just like the ones in the stories she loves. Along the way, she makes new friends, learns about the realities of the military, and starts to question the truth behind the stories that she loves so much. This interview with artist Sara Alfageeh and writer Nadia Shammas touches on their shared backgrounds, how they designed a fantasy world that draws from this one, and the role of storytelling when it comes to empire building.

-Tiffany Babb

* * *

Tiffany Babb: What was the first comic your read that really had an impact on you?

Sara Alfageeh: I know that me and Nadia share this, and that's part of the reason why we became co-creators—we very much grew up reading manga. I also had a healthy diet of Calvin and Hobbes comics, as I think many people did, but really, I would say the most formative was manga. I specifically talk in the end of the book about how romance manga actually taught me the most about pacing. The same things I learned from Fruits Basket and Nana and all of these other very high fem books are also the same lessons I took to pace out an action scene.

Nadia Shammas: Yes, we definitely were both manga kids. I was 100% one of the ratty teens in Barnes & Noble, just sitting in the shelves with all my friends. I think that Fullmetal Alchemist, both the manga and the show, are always big reference points for me. I was a big horror manga fan as well. I think that that gave me a really good understanding of how to pace a story in order to get the most impact out of a page-turn or out of a spread.

I got into cape comics a little bit later in my teen years. In my college years, I think one of my biggest impact ones was Daytripper by Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon. That really made me feel like, "Wow, comics can have such an incredible impact." Then later on, I started to pick up stuff like-- I think my first proper western comic was Sandman by Neil Gaiman, which made a lot of sense— because I was a ratty emo teen.

Sara: I went to art school because of Ms. Marvel Volume 1. I did not consider it up until that moment, not at all. That's what cracked it open for me.

Nadia: I think Daytripper was that for me for comics writing because I read Daytripper, and I was like, "This is so beautiful." It really spoke to me. I read it during a time where I started having a lot of weird death anxiety, especially as someone with a chronic illness, and I read Daytripper and it was very impactful and it made me think, "Wow, I want to do this."

How did you two meet?

Sara: I think I DMd you, Nadia.

Nadia: Yes, Twitter.

Sara: I was on a hunt for a co-creator who would put up with my nonsense and I found Nadia because she was like the only other Arab in the space.

Nadia: I think the first conversation we had was just us talking on the phone about that.

Sara: I was like, “It’s you!” Like the Spider-Man meme. We were both kind of around the same age, freshly out of college, both had Kickstarters, very scrappy comics sort of presence. I was like, “All right, you know what it takes to do this kind of work. I'm not going to have to explain much to you. You're also from New England, which is fun.” From there, it just made a lot of sense. Our first phone call, again, was four hours long. It wasn't by accident.

There are a lot of different ways to tell a story about dismantling empire. In Squire, we have the contrasting perspectives of the older people and the kids, who lack the lived experience and history that their parents and elders have but also maybe lack some of their cynicism too. Why was it important for teens to be the heroes of the story?

Sara: The story I wanted to tell was actually inspired by the fact that I was a middle and high school teacher when I was first developing Squire, and I would just listen in on the conversations my kids were having. They were just so relentless in their hopes and ambitions and their need to take action for a lot of systematic problems that I feel like people much older than them, people in their thirties, forties, fifties actually gave up on.

They were talking about climate change in really refreshing and radical ways. This was at the time when the Parkland shooting walkouts were happening, and it was the voices of sixteen, fifteen, seventeen year olds who were stepping up to say, "Adults are not protecting us." I think that resilience is so compelling, and you really do want to root for them. There's no one who wants to change the world like someone at that age where they haven't been jaded yet. It's like they understand it's their turn to step up and be part of the next cycle of change.

Nadia: I think from my perspective, something that I really thought about with Squire and just as a creator, was the way in which-- I guess the age in which I started to come into consciousness about politics and my own identity. I grew up in New York, in a somewhat segregated Arab and white working-class community in Brooklyn. I was in New York when 9/11 happened. A lot of my life and my own sense of identity was very much in the shadow of that.

When I started thinking about what kind of book I wanted to make, especially for a younger audience, I realized that I wanted to specifically address some of the difficult feelings that I had at that time. But at that time, I didn't have the education, the age, the awareness, the wherewithal to put into words where my discomfort was coming from— what it felt like to be in a country, in an empire that is actively at war with where I'm from and the dissonance between the intense nationalism that I was being taught in my school and the intense sorrow that was in my home, watching my family react to the Iraq War.

I really wanted to try to make something that could maybe spark some of that difficult relationship between identity and empire for younger Arab kids and maybe spare them some of the pain that I had to go through while trying to understand myself and my own place in America.

Sara: That's part of the reason why me and Nadia immediately clicked as co-creators is we didn't have to explain that shit to each other. Our formative memories were definitely rooted in that same experience of “You are very much guilty until proven innocent.” That does change your perspective and your relationship with how you present yourself to other people. That's why visibility is a very core theme to Squire. Who can cover themselves up? Who can't? Who has the ability to assimilate? Who doesn't want to?

All those conversations, you do have them at an extremely young age. I would even say that's why Aiza can just jump into it, because even with our own experience, we know we've been having these conversations as young as five, six years old.

Nadia: I think it's interesting because I recently obviously saw some reviews of the movie Turning Red and criticisms about it not being universal. But the big problem that it made me think of is that there are so many experiences that that non-white kids have to take on and deal with that are never shown. What ends up happening is that you just feel weird and out of place. I think by showing the intricacies of like, "No, kids are not just innocent, dumb, little—” Even if they can't put words to it yet, they're formed in the world and they're formed in this culture, so they know what's up.

I feel like a big part of Squire’s arc is Aiza's disillusionment with the stories that she fell in love with about the military. Was that same disillusionment also drawn from your personal experience?

Sara: I wouldn't say I went through the same paces of disillusionment. I would say that the path that Aiza takes where she's like, "Well, there's this clear route to citizenship and to going up in society," these are conversations we grew up with, and that we have, even if it's not my personal perspective.

Nadia: I think that a big part of that arc is specifically brought from, ironically, even though I felt the pressure of American culture just really hating Arabs as a kid, something else that I experienced on the other hand of that is the military recruitment system being everywhere in my elementary school and my high school, in my community, in my college, because I went to Brooklyn College, I went to City College, and I swear, almost every day, in the cafeteria, there was a recruitment desk. Even my mom was reached out to, during the Iraq war, for a translating job. I was reached out to in high school for translating jobs for the military, and they were like, "We'll pay your college." And that's a big deal.

Sara: It was a very common experience in the city I was growing up in [Boston] where college was not necessarily guaranteed because of the socio-economic class of the area I grew up in. I had a lot of friends who had that similar story.

I'm also just extremely interested in army culture. A lot of those interests that got poured into how we wanted to develop Squire, like the training scenes and the camaraderie that comes out of it. Also, the very different reasons for why people would join the army. Why would you put yourself in this position? Is it for the accolades? Is it because of family legacy? Is it because you don't have another option to go up in the world? Is it because this may be a path to security and safety? You don't think of what the army is going to ask you to do until you get there.

Nadia: I grew up with… not a lot of money. I remember my mom just crying in the kitchen being like, “Do I take this job because it's so much money?” Obviously, she didn't, but I’ve seen a lot of friends go to the military and change. After they came out of those programs, they never looked at me or talked to me the same way. I think just having that as part of our experience made it so that we already had military presence in our lives in a strange way.

On the other hand, the military stories were always the ones I liked as a kid, again, bringing up Fullmetal Alchemist, bringing up Avatar the Last Airbender. Bringing up Mulan.

Sara: You saw war being intertwined with our own family stories as well. That's your dinner conversation every single time. You sit down and you talk politics and all that. That is the Arab family experience.

Nadia: Yes, exactly. I think that we wanted to have a character who had the experience of disillusionment in perhaps a more direct and straightforward way, even though those kinds of conversations were already just in our lives all the time.

Sara: Squire may be set in like an alternate history Middle East, but it's very much an immigrant story. It's a diaspora story; it's about having a foot on both sides of the border. I would not say that this is like an "Arab story." I think it's so tied to that American hyphenated experience.

Nadia: Yes, I agree with that. I think that it's an Arab story in the sense that we are Arab, and we have pulled from our own culture to create this world. I think that the core tenant of the themes we're talking about, the experiences our characters go through, are the experiences of anyone whose very existence and identity is antagonistic to the desires of the empire they are in.

Speaking of the military, a lot of the aspects of Aiza's training in the military are pretty standard fare for fantasy stories, until they're not. Can you talk about the elements that you wanted to lean into in the military story and which elements you wanted to shift away from?

Nadia: I think the biggest element I wanted to shift away from was, in a lot of these military stories, you have the kid who is maybe bad at the beginning, but then becomes a prodigy and becomes the best one. I really wanted her to just absolutely fail and just show that she does not have a natural proclivity for this. She doesn't need to. She's a kid.

Sara: Squire originally started as a very high fantasy concept. That's what my sketches were like when I was developing it, before I ever realized it would ever become a real book. Then I had a really great mentor talk to me about why I wanted it to be a high fantasy story and really forcing me to be critical to the design choices I was making. Essentially, he was like, “Well, you want to talk about marginalized experiences, and you want to talk about these different kinds of prejudices. So why don't you just talk about it? Why do you have to make it about orcs and stuff?”

I was like, "Shit, you're right." I wanted to draw pointy ears, but whatever. I peeled back a lot of those layers because I realized I had to be very honest about what I actually wanted to talk about, and I didn't have to beat around the bush. I was like, "Yes, fuck it. It's a Middle Eastern setting. You're going to recognize Petra, you're going to recognize these environments. Let's get into it."

At the same time, because we don't create stories in a vacuum, I had to also accept that I needed distance from the real-life conflicts, the real-life politics so that people didn't box us into the narratives we were dealing with in our everyday lives. I needed fantasy to talk about a very honest story.

Nadia: I think that there's this huge problem when marginalized people make fantasy based off their own cultures that we have to be these experts on every aspect of our culture and our history and everything has to be represented perfectly and there's a magnifying glass where people are like, "Okay, so you're talking about this country, and you're talking about this conflict.”.

No one does that to Game of Thrones, right? No one sits there and is like, "Okay, George RR Martin is talking about England right now." There's a certain trust or grace that is given to white fantasy creators that is never really given to us. I think a big reason that we chose making an all-world fantasy world is that we want to be given that grace. We want people to not try to push our story into one specific history, or conflict, or country. We want to have the trust of our readers to give us the space to do whatever story we really want to do.

Can you talk more about the process of world-building with pieces of the real world and how you created the world of Squire?

Sara: Once me and Nadia finished doing five-hour phone calls every single week, and we decided we wanted to do a book together, I took a trip to Jordan and Turkey, and I just did a whole in-person research trip where I collected my own reference photos. I went around country sides and ruins. I went to Petra. I went to the Hagia Sophia. I wanted to just take away as many colors and designs and details from the regions as I could and bring it into the comic. I wanted to make it clear we were the best people to make Squire happen, and we were coming into it with a very informed approach.

We weren't just pulling aesthetics willy nilly, it was all intentional. Because there's so much range and diversity in architecture and designs and ethnicities and features all throughout the region. We wanted to make sure that they felt rooted in something recognizable. I don't mind that you can pick out Petra, that is a real place and it feels fantastical, the same way that we know where the Shire is. I wanted the world to feel rich and informed and just exciting even when there were no words on the page. I wanted the environment to step up and feel like a character like everything else.

Nadia: I think world-building is so important because you want your characters to feel like there are from a world, from an active world, that there are perspectives and their clothing and everything about them comes from history and geography and just a real place. Because I think that makes more compelling characters. We both did a ton of research. I did a bunch of research into Ottoman and Byzantine history, into sword fighting and why the Ottomans use curved blades, and it was a geography reason because curved blades worked better on horseback. I remember sending Sara medieval YouTube videos from a medievalist about how they put on saddles during that time. It was just really fun to do that work and very--

Sara: Eating chips for us. It is so self-indulgent.

Nadia: Oh, absolutely. We're both just big history nerds.

Sara: It's a foot in the past, a foot in the future. That's ultimately like what empires are always concerned with. It's who we were and who we're going to be. It's that intense nostalgia for what you could be as well. The first speech that we have from our general is all about how far they've fallen and that it's their responsibility to now step up and make things great once more.

Speaking about costume design, can you talk about how you design a character through pulling things from history, but also with the character's role in the story in mind?

Sara: First things first, I have to draw everything a thousand times. That is the main design principle, “How do I not die?” Then I go from there and I try to simplify it. It was very fun for me designing the Squire uniform, figuring out how it would be practical, functional, how it would look like in sword fights, in horseback rides, and how it would look on different body types and different characters. And then going from there, just thinking of silhouettes and of how these different characters present themselves. I always wanted General Hende to feel larger than life. She always has such a dominating silhouette. With the cape, she can make herself taller as different events require her to be. That way when characters are in less favorable positions, you can reflect that with their character design.

Aiza’s design changed a lot from when I first conceptualized the book, and it was hard to pin her down. She had to be the runt of the litter. I had to design who was going to be around her in order to make sure that landed. Designing our one-armed mentor, Doruk, was extremely fun, a very self-indulgent design. Making these two characters who end up in understanding each other best, I wanted them to present to themselves as fundamentally different. There couldn't be more polar opposites than those two designs in particular.

It's a big aspect of the book, and having fun as well, with the background characters, making people understand this region both in real life and in fantasy is incredibly diverse and rich. I'm not making up who is featured in this world. These are all faces and features that I've grown up around, whether in my own family or among friends and relatives.

Nadia: I think I remember specifically, you and I, Sara, in the back of a taxi in New York, talking about the characters and specifically being like, okay, so we know that we want to come from a fantasy perspective, a real love letter to the tropes. We knew we wanted a big strong girl who could kick ass. We wanted the cocky legacy kid. You know what I mean?

Sara: Like the Draco Malfoy.

Nadia: Yes. Like the Zuko.

Sara: If we have this kind of character, we want this character to balance it out. We have the runt; we need the strongest kid in the group. If we have the kind of spoiled rich kid, well, we need the rich kid who's worried about his father's opinion.

Nadia: Also, we wanted all of these kids, from the very beginning, something that was very important to us to reflect the ethnic diversity of the Middle East, because we don't really see that a lot in stories about the Middle East. We definitely wanted to show how absolutely diverse and rich that area of the world is. It's massive.

A big theme in your book is the power of stories. We see Aiza obsessing over the knights and how the military is portrayed, and then later on how the story affects Aiza's role in the military. Why was it important for you to depict the power of manipulative storytelling?

Nadia: I have a really big interest in the way that histories are told. I think the biggest turning point in my life was realizing that all the histories I knew are simply narratives and are no more necessarily factual or honest in their intent than any novel or a book or essay that I've read. I think that especially also is my experience as a Palestinian. I watched the way in which history is shaped to reform, restructured in order to give credence to whatever awful thing is happening, in order to justify it, and the way that that misinformation is used to get people on the side of a colonizing empire.

American history is exactly the same, right? You learn a version of it and then if you're lucky enough, you have access to good higher education or to a kind of learning that requires you to basically re-look at the history you were taught and realize that all of that is absolute bullshit.

There's a line that I wrote that I personally consider kind of the thesis statement of all our antagonists, which is: history is the story we tell about ourselves. Because history genuinely is whoever is telling you your history is telling you who you want to be.

I really wanted to give kids, especially since this is a book for younger readers, kind of the ability to maybe read this and then start to question, “What are the stories that I've been told? What are the things I believe about myself that may or may not be true because I've been told to believe those things?” Then to figure out what-- as far as not trying to answer any questions about what to do when you're in an empire and what's your culpability and how should you feel, it's just looking to maybe give you some tools to take a second look at yourself and what you think and hopefully begin to ask the questions of, “Who am I? Who am I outside of what I've been told and who am I because of what I've been told?”

Sara: It's all made up, and we want to talk about that. It's our lived experience, and it's all made up, and it's interesting to find out that you identifying or presenting yourself in a certain way really does benefit certain people. It's important to know who would benefit and why. I've always been fascinated by the kind of stories that compel us to take action. We see it over and over with every kind of empire. They have a very clear narrative of who they are, who they're meant to be, who they want everyone to be. Those stories are powerful, and it's fiction like everything else.