Celestia, the latest book by Manuele Fior, was published in Italy by Igort’s Oblomov Edizioni between 2019 and 2020 in two volumes; it was released in English by Fantagraphics this past summer. The book marks Fior’s fifth release in English, making him the most-represented Italian comic artist in the North American graphic novel market.

In Celestia, Fior takes us to a fictional Venice of the future, a city far away from the rest of a world in ruins, where a group of young people are developing ESP powers. Two of them try to escape their fate, and the book follows their path to freedom and self-discovery.

One year after Celestia was released in Italy, I had the chance to meet Manuele Fior in Venice; I was visiting a city completely different from the Venice everyone used to know, now without the usual multitude of tourists. Manuele had just moved there, to the city that inspired his work, after living in Paris for more than a decade.

More recently, when the book was released in English, I had a long chat with Manuele about how Celestia was born and what inspired it. This was probably the third interview I conducted with him: one was for Linus magazine a few years ago, and one was for Fumettologica, when in 2016 he released his “flag comic”, a giant comic as big a poster, published by Ratigher’s Flag Press (which also published a story by Simon Hanselmann in the same format).

* * *

Valerio Stivé: I think Celestia is an important book in your career, because there is so much of you in it, both as an artist and as a individual. What brought you to do a book like this, that is so real and fantastic at the same time?

Manuele Fior: I started working on Celestia five years ago, and the reasons why I did a book like this go a long way back. The idea comes from a time when I wanted to distance myself from my early works. I started my career in comics doing autobiographical-inspired comics. My first book, which never got published in Italy, was entitled The Sunday People, and tells the story of a young man who is going to leave for Berlin. Then some things happen and in the end he never leaves. It was inspired by all those autobiographical graphic novels that were popular during the '90s and early 2000s.

Manuele Fior: I started working on Celestia five years ago, and the reasons why I did a book like this go a long way back. The idea comes from a time when I wanted to distance myself from my early works. I started my career in comics doing autobiographical-inspired comics. My first book, which never got published in Italy, was entitled The Sunday People, and tells the story of a young man who is going to leave for Berlin. Then some things happen and in the end he never leaves. It was inspired by all those autobiographical graphic novels that were popular during the '90s and early 2000s.

Book after book I’ve always taken elements from my own life and used them in my stories. But now I also felt the urge to play with the great ability of comics to tackle the fantastic, while also doing justice to my early days as a comics reader; and as you know, I’ve always been a fan of American superhero comics. But American comics [in general] are still hugely influential to me as a comics creator, also those from very beginning, like Winsor McCay's Little Nemo.

With Celestia, I wanted to take advantage of the great familiarity that comics have with the fantastic. It is comics' own peculiarity, so much that it makes them of great inspiration for other mediums, like cinema. So many ideas of cinema come from comics; think of how Moebius’ imagery is behind so many movies.

When I started working on Celestia I wanted to draw a line to separate me from everything I had done before. I had flirted with reality, but now I wanted to something completely different and distant, to see what could happen.

There was magical realism before and now it seems like you’ve embraced a personal idea of fantasy.

Yes, I’d rather say a realistic fantasy for Celestia, the opposite of magical realism. Since 5,000 km Per Second and especially The Interview, my storytelling started distancing from the ground, and now took flight with Celestia.

Actually, in the book there is a lot [of] realism as well. To be honest I find it so difficult to distance myself from reality, or maybe I just don’t want to. To me, everything has to start from a realistic context. The city of Celestia has basically the same origins as Venice, which was born when the population of that region tried to escape from a barbarian invasion coming from the East.

I’m just reloading an old story that is already quite incredible itself. I’m just shining a light on something real to show how fantastic that actually is. Even by changing the name of the city—from Venice to Celestia—I’m just telling the reader “you have become accustomed of the existence of this city, but if you think about it [it] is nothing short of amazing.”

Even the choice of setting the story in an alternative version of Venice shows a great influence from your own past, because you’ve lived there in the past. How did your story get there?

All the comics I’ve done so far needed a very specific setting. It would not be possible for me to create a setting out of the blue, just like in Moebius’ 40 Days in the Desert. That probably started when 20 years ago me and other young cartoonists used to bring stories to Igort, stories where we drew things we never actually saw in real life. And he was always like: “did you really know these things firsthand?” We drew urban landscapes with the typical New York buildings and their water tanks on top, but [we'd] never been there at the time. So Igort always came at us with brutal honesty saying you should only draw things you actually know.

Then, when I started working on Celestia, I had this sci-fi story in my head, and when I was looking for a location Venice sounded like the perfect idea. Because I’ve lived there when I was younger, and it was more than 20 years ago. It was perfect. In my mind, the city was already transfigured by time and memory. Like on old bottle of good wine.

Memories made it more malleable.

Yes, but not only. Memories took it to a different level. I’ve lived 13 years in Paris and aside from a couple of short comics, I’ve never set a graphic novel in Paris. Because I always find it too hard to confront myself with something that is part of my current life. I need to [distance] myself from something to understand what I’m really interested in. So it was for Venice.

To make a few examples and go into detail, many episodes in the book are transformed memories. When I was young and I arrived in Venice, I was looking for a place to stay and I crashed at the apartment of two older girls. They took care of me for a few days, I was just out of my parents’ house and I wasn’t able to do anything on my own. It quickly became an ambiguous situation. This scene appears in the book but it is completely different, transfigured by memory and imagination.

When people asked Fellini what kind of Rimini is the Rimini in the movie Amarcord, he used to say that the city from movie has nothing to do with the real Rimini - “that is my Rimini”, he said. That is something that comes of the artist’s imagination, so in the end it has almost nothing to do with the original.

Then, when you actually work on the story, all these ideas I’m trying to explain now, they translate into a physical pleasure and an urge to go back to that place. To me comics are always like an enterprise. Not in a business-like sense, but in the sense that it involves traveling, reconnect[ing] with people I lost touch with, etc... And I like it. Now what’s funny is that I ended up living here in Venice.

In Venice you studied architecture...?

Yes, then I studied a year in Berlin, where I stayed several years and worked as an architect.

What did being an architect bring to you as a comic artist?

I had a troubled relationship with university but a pretty good one with architecture. I’m still in love with the job. In [my] next life I’ll be an architect, I promise. My education as an architect gave me a lot. Unlike those who become a comic artist after attending a comics art school, I started my career in comics following a zigzagged path. I did many different jobs, and they were not exactly related to comics.

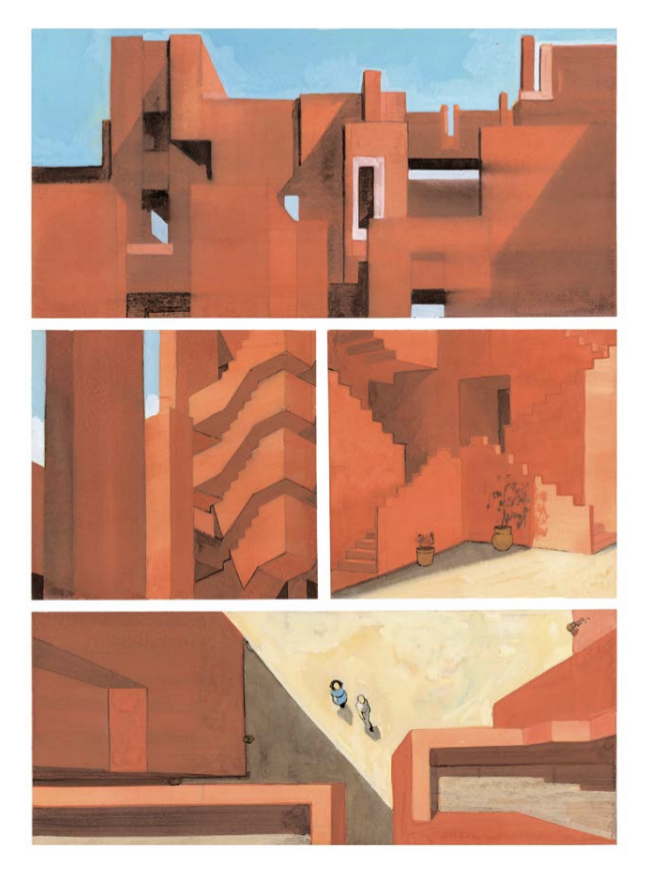

Architecture forced me to widen my view, it allows you to work on many different disciplines, often leaving your studio, talking with people who work with their hands and do heavy jobs, and you have the chance to sharpen your view [while] also learning to take photographs. Focusing on architecture taught me to forget about anything that was popular in the world of comics at the time, and to [leave] behind every influence from other comic artists. And it is still relevant now. A sketch by Le Corbusier, Wright or Mies van der Rohe still moves me, and I want their influence to be visible in my comics. As much as the influence from Picasso or Modigliani.

How did you choose to start a career in comics?

It all started in Berlin, I guess it was the year 2000. There was a small comic convention, and Igort was a guest, as well as Stefano Ricci. Igort told me he was going to start a publishing company, Coconino Press. I was working as an architect at the time. In Italy, before Igort started Coconino, there wasn’t much you could do if you wanted to publish your comics outside the mainstream business (mainly Sergio Bonelli Editore). There was the magazine Mondo Naif, and not much more.

When Igort told me what he was going to do, with his peculiar and charming way of telling things, I immediately fell in love with the idea of seriously concentrating on doing comics. I didn’t even know what to do exactly.

At the time I discovered L’Association and I loved what David B. was doing. Blue Pills by Frederik Peeters was just released and it was very influential to me. That was the kind of comics I wanted to do. I wanted to tell something real, my own life. But then I soon realized I wasn’t able to make autobiographical comics.

In Celestia there are many things you love. American comics are a huge influence, and you basically make your own version of the X-Men. Architecture is a huge influence, with many references to existing buildings. And animation as well; mostly Hayao Miyazaki and his Future Boy Conan.

The books [are] basically an attempt to bring together everything that has fueled my love for comics along the years. And animation is probably the oldest of these. I started making comics thanks to animation. I fell in love with it in front of the TV set when I was a kid, in a time when Japanese animation invaded Italy. I’m so grateful for that and for those amazing stories and worlds.

What inspires me the most is the great synthesis that traditional animation has reached. Just think of those painted backgrounds with simple characters that move in front of them. It’s quite weird actually, and I still find it so fascinating to see those two different kinds of styles together. In Japanese animation, even the cheaper productions can show great intuitions. I once talked about this with fellow comic artist and animator Claudio Acciari who showed me some scenes from Aim for the Ace!, and on the backgrounds it had amazing abstract paintings that looked like a Pollock. When you are a kid and you see such images, you just don’t pay attention to it, but if you look at it now, that is pretty cool. I find Japanese animation so inspiring. American animation as well. Or some Italian classics like Bruno Bozzetto’s West and Soda; Giuseppe Mulazzani worked on that and he was such a great artist, that in a such a funny cartoon he could show influences from artists like Paul Klee, just to name one.

I can see that in your comics, this kind of balance between simple characters and beautifully painted backgrounds.

And yet, to be honest, I’m not into painted comics. I’ve always preferred black & white or flat-colored comics. Obviously, there are some exceptions, Lorenzo Mattotti being one of them. He does something great with painting techniques. But not everyone can do that, and I’m just trying my best.

In Celestia there are also influences from cinema, I could mention Kubrick. And influences also from art; some said that there are panels that look like a Rothko painting. The whole book could be considered as one of many attempts to show how comics can be fueled by all kinds of arts and mediums. Just like Mattotti and the Valvoline group already proved in the '80s, experimenting with cinema, design, fashion. I’m not doing it to show off, I’m just doing it because I want comics to be as beautiful as possible.

What to do you enjoy reading now?

I enjoy things from the past much more than the contemporaries, but I try to keep up with what’s new. This year I loved the first book by Miguel Vila, Padovaland. But I think there is a lot old stuff still to be discovered. I read a lot of Japanese comics, a lot of Tezuka, and also Katsuhiro Ōtomo and Satoshi Kon. I love Satoshi Kon, his short stories are incredible.

I enjoy things from the past much more than the contemporaries, but I try to keep up with what’s new. This year I loved the first book by Miguel Vila, Padovaland. But I think there is a lot old stuff still to be discovered. I read a lot of Japanese comics, a lot of Tezuka, and also Katsuhiro Ōtomo and Satoshi Kon. I love Satoshi Kon, his short stories are incredible.

And I read a lot of American comics as well. I like to rediscover Golden or Silver Age comics, to see if I would still enjoy the stories I’ve read when I was a kid. Some of them are incredible, and still of great inspiration. Like Elektra: Assassin and Elektra Lives Again, especially Assassin, are such great iconic books that are made of everything I would love to be able to do: great balance and synthesis in story and art. I’m currently rereading Sin City. I’ve read Claremont and Byrne’s X-Men many times, and some Spider-Man stories, like those by Roger Stern, or the stories between the arcs of Romita Sr. and Romita Jr.

I love reading Winsor McCay['s Little Nemo]; it’s not [a large body of work] but there was already everything there. And I enjoy reading many contemporaries from [the] U.S.A. and Canada. I love Chester Brown. I love Blutch, his new book with the characters Tiff and Tondu is amazing. And several other contemporaries like Frederik Peeters are friends as well; I love his latest book.

Getting back to Celestia and Venice, you said you are currently living in Venice, but at the times you were working on the book you were still living in Paris. So once the book came out, you moved to Venice. It’s a weird coincidence.

Yes, once the book was released, I moved to Venice, and then the world went into lockdown. In retrospect, this is probably the most interesting thing about Celestia. By the time I finished the book, COVID-19 [didn't] even exist. I did my first lockdown in Paris, then I decided to move back to Italy and live in Venice. Last year, in Venice, I basically lived inside my book. Venice was empty, and some sceneries outside the city looked so much like those in the book. I remember once I [was] walking along the beach with my family, and we saw the Palazzo del Cinema with its weird shape, it totally felt like being in one of the landscapes in my book. To be honest, and I don’t want it to sound like nonsense, it made me think that sometimes when you are so focused on something you can feel some vibrations, like you could notice something even before it happens.

I just think that there are other forms of communication that go [beyond] those we normally use. The whole theme of telepathy in the book: it’s all about this. During the first lockdown, I remember all these people singing outside their balconies to keep themselves company and give comfort to each other. It made me think of a scene I had drawn in Celestia, when almost at the end of the story there are kids on a balcony who start talking in unison. This kind of reaction we saw in real life was spontaneous; coming together like this must be something that human beings do to react to difficult times. Something that is as old as the world. The whole image really had an impact on me.

I’ve read a few reviews of Celestia and some of them point out environmentalism as one of the main themes in the book. I tend to agree on that, do you?

Yes, as far as migrations have to do with the environment and climate change. It was important to me to speak about a migration coming from the south, just like the one that is happening in Europe. And the current phenomenon of populations coming from Africa is a consequence of climate change and political changes. The whole political balance in our continent is changing. Pasolini figured this out in the '70s, in the poem I quote at the beginning of the book.

[But] I don’t like my book to be considered as part of a specific genre. I’m not a big fan of putting works of art into pigeon-holes. To me, books shouldn’t have be limited by any boundaries imposed by genres.

This makes me think I have the impression that your work is based on improvisation. Am I right?

Celestia totally came out of improvisation. I’ve read a review that said I stayed in my comfort zone. That made [me] laugh so much. I was completely out of my comfort zone. I was outside under a pouring rain. With this book I tried to push my boundaries as much as possible. And by improvisation I don’t mean it is done randomly, coming by accident. The characters came out spontaneously, they grew up in this universe that was already there in my mind. But at the beginning I didn’t know how the story was going to unfold. And I didn’t want to know that.

My main influences were The World of Edena by Moebius, or Little Nemo by Winsor McCay. The kind of stories where there is no greater plan and everything is added a little at a time. [These] kind of comics are not written like a movie, with a storyboard, etc. These are different narrative forms - just like Moebius used to say, there are comics shaped like a house, or an elephant, a cornfield, or a match, and there are also narrative monsters. To me Celestia was an attempt to test myself on finding the most surreal ideas, in narrative terms, using automatic writing techniques.

At the end of the book, after seeing the character running away so desperate, I think that the story shows a great trust in the future, it has a positive momentum.

I don’t remember who used to say this, I guess it was Antonio Gramsci: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. If I was too pessimistic, I wouldn’t get out of bed in the morning. Yes, I want my characters, who basically represent humanity itself, to find a solution and [not to] succumb. Then there are characters who manage to do that and others who don’t.

Pierrot embraces violence rather than embracing this new step of evolution that is telepathy, while Dora believes in it and tries to go for it; and there are kids, who represent something new for the humanity, the future. This is an old idea, that you can find in the Bible, when Jesus Christ is a kid and speaks to [the] priest like a wise man; there is an amazing novel by Arthur C. Clarke, Childhood’s End, where kids have great powers that can save humanity; or think of Akira, where kids are a new step in the evolution of humanity. And that’s what they actually are.

If you are being honest, creating a story allows [you] to show the way you see the whole world. And the way I see it is that as bad as it looks, every day you can always find a good reason to go on, face a new challenge and evolve. I believe that, and I don’t think we are bound to extinction.

5,000 km Per Second is widely considered by critics as a milestone in your career. And now, looking at Celestia, we can see so much of you in this book to make it so relevant. Do you really think there is such a thing as a milestone in your career? To which of your books do you feel more attached?

5,000 was important, that’s for sure. It was also a challenge to me, a complicated book, the first one in full color. But I know that each book you make is seen in a different way by the readers, regardless of the effort you put in it.

I think The Interview hasn’t got the attention it deserved, yet to me it is such an important book. I find it even [more] flawless then Celestia. But if I started a new book with the only intention to make a more flawless book than the one before, I don’t think I’d be able to come up with something really good. Every time I start a new book, this starts as a milestone in my head, a new turning point. Every book changes the way I work. I wouldn’t start a book without the belief that it is going to change everything for me.

I am currently working on a new book in a totally different way than before; it is the first one [where] I’m drawing a storyboard, and there is no other way I could have done this book. I’m excited about that, you may never know how other people will see your books, and you have no power over that, but that’s okay.