There is a world of comics completely disconnected from the genres in which traditional comic book retailers specialize; one that’s equally separate from the world of small-press and independent comics The Comics Journal prides itself on covering. This ecosystem is considerably larger than the one I know, with many more readers. It's a world major book labels dominate, publishing work intended for an audience of children. The authors have agents and get advances for their work. The sensibilities of the artists involved are distinct from the well-drafted absurdism that gets cartoonists jobs working for Cartoon Network. The exact rules by which the game is played elude me, but I know this is the new profitable playing field.

If graphic novels are viewed as an emerging literature, then YA is even newer on the scene, and has retroactively claimed a few preexisting comics as part of its lineage. Maus, like all of the classic literature students read in school, was not originally intended for a young audience, but over time teachers and librarians recognized its instructional value. Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World takes teenagers as its subject as part of a larger attempt to invest comics with virtues of prose literature for adults, and favors an elliptic approach that might not even count as a story in the eyes of someone accepting proposals for books based on a pitch outlining its arc. It is because of this ahistorical claim-staking that I can’t just ignore YA work with a “well, that’s not meant for me.”

I grew up reading comics that, if not explicitly intended for children, were certainly aware by the nature of being a comic and by comics being easy to read that children would form a large portion of their readership. This includes superhero comics as well as newspaper strips. Plenty of these works contain material that either went over my head at the time, or read differently to me now, but largely I was unbothered by the content. There’s also not a few manga explicitly labeled as being for adult readers as translated to English that were marketed to and enjoyed by young readers in Japan. For all the cultural differences, I understand and appreciate the intent to entertain behind these works. As an adult, I often read and enjoy work I would take no exception to much younger readers consuming, and not just because I believe in letting people read what they want - I acknowledge that I am often the interloper.

I am aging and encountering something new to me. These comics leave me in a place I think most working people in America, particularly if they’re artists, are often at: I recognize a value system in place that is not mine, but needs to be understood on some level if one wants to survive. To try to get to the bottom of what, exactly, is the deal with YA and middle-grade book market comics, I sought the insights of people in a position to know.

* * *

GINA GAGLIANO was the associate director for marketing and publicity at First Second Books, a comics imprint owned by Macmillan, who moved to Penguin Random House to form her own imprint, Random House Graphic, which she recently left. She has since been appointed executive director of the Boston Book Festival.

Brian: When you started the Random House Graphic imprint, what did you want it to be, or do?

Gina Gagliano: Random House Graphic’s motto is “a graphic novel on every bookshelf.” That’s still their motto, that’s still what the amazing people over there-- the current publisher, Michelle Nagler, senior editor Whitney Leopard, senior designer Patrick Crotty, and editorial assistant Danny Diaz, that’s still what they’re doing. But what was really behind it was this idea of creating comics for everyone in America, and getting kids starting from age four excited about comics, and having graphic novels across different genres or age categories or about different topics that they could read and get into comics as lifelong readers.

When you were a child, what did you look for in a reading experience? And how would you ensure you capture that when looking at work to publish?

This is an interesting question, because when I was a kid I didn’t read comics. I grew up in a small town-- the library in the town, the bookstore in the town, didn’t have comics in them. The way for me to get comics, as I discovered when I got to college, would’ve been to convince my parents to drive me half an hour to someplace that had a dedicated comics shop. But I didn’t even realize that was a thing I could ask for. So I have all these reading experiences from when I was a kid but none of them are in the comics format.

You can talk about prose too. That’s an important reading experience, and novels provide an emotional connection that I’m sure you’re still interested in as you look at comics.

When I was a kid, and still today as an adult, I read a lot, and I read across different genres, across science fiction and fantasy, across mysteries, non-fiction, contemporary, there are all these different kinds of books. It’s interesting that sometimes one person is reading all these different kinds of books and sometimes one person is like “there’s one of these specific categories that I really find to be up my alley.” I think all the different categories have different things about them that people find exciting and intriguing. Overall, I like really compelling characters, I like emotional storytelling, but when you’re thinking across food non-fiction, which I really like to read, and mystery novels, it’s hard to say “here’s the one thing I find compelling about everything” because-- you know, good writing. When there's art in the book, great artwork. And beyond that, it really depends on the type of book, and the individual book.

What do you find appealing in a visual style or an artist?

I like art that has a distinct style, where I can kind of see the personality of the story in the artistic style. That spans a whole lot of ground. I feel like people do amazing things with different art styles. Art is so cool. I don’t know that beyond that, beyond having an art style that works with the story, that there are specific things about the artwork that need to happen in every story, in every piece of comic art that I see.

I want to make distinctions between your personal tastes as a reader and what you have learned over time the audience responds to, because you were at First Second from the beginning, and at the beginning you started off with translated work, but then the work that I think of as being the actual hits—Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese, Mariko and Jillian Tamaki’s This One Summer—came from North American creators. I hate to use the term “brand identity,” but as you realize “this is what the audience wants,” are there things you hone in on, rather than perhaps the earlier experimental phase of thinking “ok maybe this European stuff will connect with readers” and learning that it doesn’t, to seeing what works and learning what you’re seeking in a North American author?

When you sent this question to me, you had this question of “how did your vision of seeing what succeeded come together?” And I feel like thinking of that while I’m thinking of the answer to this question, because Random House Graphic started off with doing some graphic novels in translation, and First Second throughout their history have as well. And one of First Second’s founding principles that director Mark Siegel has built into the vision of the company, is the idea of books building bridges between readers. And one of the bridges that he sees is bridges between countries and bridges between different people and different experiences around the world. And so that’s been important to First Second throughout their history, and looking at their publishing list today, [they're] still publishing great works in translation.

But the question of how that ties in to success is “are the books in translation a success?” And it’s a complicated question, because different publishers look at what a success is in different ways. Even within one publisher, what a success is can be different for different books, right? So I think most publishers that I know would say sales is a factor in determining what a success is. But not always. There are books I would say sold well that publishers would say this is not a success because of other factors. Or books that sold poorly that publishers would say is a success, because of other factors. Looking at winning awards, looking at the financial profile for [a] book, did an author earn back their advance, are you at a point where the client has earned out, and you’re paying royalties? Looking at the media success of a book: who is talking about it, what coverage did it get? Some success is about getting acclaim in a specific community: [for] this book a publisher is like “we’re gonna publish this because we really want to reach the academic audience, or political readers. And if we can reach those people and get them on board with our company and start that process for future books that we’re doing, that’s a success for us.”

A success can be something that is meaningful to individual readers. People are responding to [the book] emotionally and [it's] making a change in people’s lives, which you can somehow discern through... sometimes social media, sometimes getting feedback in letters or emails that you get from people. You can think about success in a different way in terms of the author. Is the author happy with this book and how it was published, and did it make their career better? And so when you think about success, First Second as a company, I mean I don’t work there anymore and I haven’t worked there for five years, but as a company thinking about their principles as I knew them as I was there, about building bridges between people in different countries and sharing experiences with U.S. readers, success can be about not “is this book the best-selling book at First Second of all time?” but “Is this book contributing to the mission of this company?” I don’t know if that answers your question.

At first, I think First Second was publishing work for an older audience, and that shifted over time to a younger audience. And when you start RH Graphic, that’s specifically for younger readers. So how do you over time come to realize what it is that a younger audience responds to, as they’re the more passionate demographic?

First I would just say, First Second still publishes a lot of great books for adults. You can see their World Citizen Comics series, which is aimed at adult readers, has been really taking off in the past year. Shadow Life by Hiromi Goto and Ann Xu was just named a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize, and it won the APALA [Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association] award for adults. The Adventure Zone graphic novels, which is an adult series, have been some of the bestselling books they’ve ever done. So they have what I think is a pretty strong adult list and a lot of commitment to that category.

First I would just say, First Second still publishes a lot of great books for adults. You can see their World Citizen Comics series, which is aimed at adult readers, has been really taking off in the past year. Shadow Life by Hiromi Goto and Ann Xu was just named a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize, and it won the APALA [Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association] award for adults. The Adventure Zone graphic novels, which is an adult series, have been some of the bestselling books they’ve ever done. So they have what I think is a pretty strong adult list and a lot of commitment to that category.

As far as thinking about kids and what kids are excited about and what to do in that space, it’s interesting, because commercial kids' graphic novels is a relatively new space in the market. It’s not like middle-grade children’s prose fiction, which you can be like, what were people in America publishing in 1940 in this space and how has that changed between then and now in 2022? I look at that space and I see the market is still being built, and the market is still being created, and there’s still categories that there’s still nothing published in, so it’s hard to say if, say, middle grade historical fiction graphic novels are a popular category for kid readers because in the past ten years, we’ve got a total of five or six books published in that space. So I think what publishers are now doing is both publishing in the categories that they’ve seen work really well in graphic novels specifically, and trying out books in these other different spaces and seeing what works when you’ve got an amazing author and a great story. It’s hard to say what the market is going to look like in 20 years because so many different things are happening right now, and people are trying different things. And I think how the market looks in 20 years will be a response to what successes people have now and in the next 5 to 10 years.

But you got to be sort of a pioneer in this emerging space, right? So once that starts to happen, how do you know what you want? When there’s very little precedent for what a middle grade graphic novel is, how do you conceptualize what the parameters for that are going to be?

When I was starting Random House Graphic, I had a lot of conversations with the people at Random House about what they thought. I pulled all my experience with publishing together and did a lot of thinking about that. I talked to a lot of people around the industry. I looked at sales numbers. But a lot of those decisions about what is Random House Graphic going to do, and what’s important here, were things that I was conceptualizing. Me saying “Random House Graphic is going to publish graphic novels for kids starting at age four because it’s important to have lifetime readers” is something I think is important. That’s not necessarily based on [if] I see a sales trend, or I’ve done extensive market testing with four-year-olds, but based on the vision of an American graphic novel readership that I kind of have in my head.

Over the past decade or so, as the YA market has exploded, in both comics and prose, there’s a greater sense of what that kind of material can address, especially regarding LGBTQ content. So people that are big readers of YA material are always saying “you can cover so much in a YA format,” but as somebody didn’t grow up in an era where this content was covered in material for a young audience, what is it in the approach that makes it a YA book, rather than an adult one? Which is not to say that I think LGBTQ material is inappropriate for a young audience, but I wonder how you approach it in an approachable way.

This is something that people in the YA space talk about all the time. I also am a person who didn’t grow up reading YA books, because the YA category became a section in the bookstore market in the prose space in the late '90s, [although] people had been publishing YA books for decades before that. So while comics are an exciting and developing form, YA is still a relatively new and developing form, and ideas about it are still being discussed and changing. And I think YA is also a fascinating space, [with] comics, prose, all the different ways people are telling these stories. Talking to people who do YA academia, YA thought, teachers, librarians, all those things, it seems like the concept for YA books is really about centering young adult characters—so characters who are in high school and college—and centering their experiences, the experiences they’re having.

So as far as what else happens in the content, it’s all about the content’s relationship to that audience. You know, I really think that there’s so much discussion of “can X topic be appropriate for kids and teens? Can X topic be in a teen and YA graphic novel or a book,” and the answer to that is really in most cases, of course. Complicated topics, LGBTQ content, discussions about race and racism, discussions about religion, all those things can be in YA books, it’s just a question of how you approach them. You can have a book about something that is complicated and serious that is for four-year-olds, and you can have a book about that same topic for adults. Whether that topic is something like grief and loss, which of course there are so many picture books about, because there are kids who are dealing with parents dying, grandparents dying, those really tough life experiences, and that book is going to different than the 400-page literary novel aimed at 40-year-olds about grief and loss. Something like Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Sometime More Pleasant?-- there’s not going to be a version of that for four-year-olds, but there is another books for four-year-olds on that topic of your grandparents are getting older and how do we be good grandchildren and children of them.

But how do you, as an editor working with an author, help an author tailor their work to the audience that you are trying to reach?

It’s really different on a book-by-book basis. When I’ve looked at book proposals throughout my career, one of the things I look for is someone who has a vision of the story they want to tell, and that story, that author is someone I want to work with, that story is something that tells the story well and is going to connect to the readership. There’s some stuff that I look at and think about as I would be working with the author to edit the book, which might be about pacing, panel count. Difficulty of vocabulary is something I think about a lot in the four-to-eight-year-old age category and not so much in the YA age category, but all those things about how does this comic look, how are the storytelling pieces of panels and spreads and word balloons and number-of-word-balloons-a-panel happening in a way that is acceptable to the readers-- but beyond that it’s about reading that and saying, does this feel emotionally resonant? And also just being well-read in the age category, reading other kids’ books, YA books, and saying “does this feel consistent with the kind of work that’s out there, with the kind of work that teachers, librarians, booksellers, readers, are responding to?”

It’s funny you mention panel count. Some of the early First Second stuff reprinted European material that’s printed much larger than the U.S. trim size that, when reduced, loses a lot. So when you’re talking to an author, is there a sense of “hey maybe don’t work so large, don’t put so much on a page,” and what would your upper limit be in terms of what you think reproduces well for the book format you have found readers are most interested in?

I think this is very interesting in the kids’ space, because we’re talking about this age range of four years old through college, and of course things are wildly different between four-year-olds who are just starting to read and people in college who are like “we’ve got it, we’re basically adults in our ability to comprehend any kind of narrative visual devices.” So there’s that caveat. And I think kids are really sophisticated readers. And you can see that in, you have Frog and Toad, which is basically line drawings, and you have Where’s Waldo?, which is all of the visual imagery packed into every page of that book, and kids love both of those things. So there’s not so much a hard and fast rule of things always need to be really simple for kids. There’s the ability to exist on that scale from the most complicated visuals--

Where’s Waldo? is printed much larger than the average graphic novel.

That’s true. But you can imagine something with the density of Where’s Waldo? at contemporary graphic novel size.

But you as an editor, if you look at something that’s super visually dense on every page, you’re gonna go “oh this is really hard to read.”

Yeah, definitely. It does depend on the story. I was just reading Alina Chau’s Marshmallow & Jordan, which is this really emotional story about a girl and an elephant and it’s so good. And the pacing is fascinating. I don’t want to say there’s so few things happening on every page, but there’s so much happening in the art, and it’s so decompressed, and it’s this great older middle grade, YA graphic novel. And it works for that book. And then you have graphic novels like Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales by Nathan Hale, where there’s so much action crammed in everywhere, and that really works for that book. I do think, rule of thumb as a whole, when you’re doing younger books, thinking about making the pacing more decompressed, having fewer word balloons per panel, having fewer word balloons per page, definitely is a thing. But there’s a lot of variations within that, there’s not one way to make graphic novels.

I have questions about speed. If you’re doing a series, because series can be really successful, you want an artist that works at a fast pace, because especially if you’re going after a younger audience, you need that audience to not move on to other things in the time between books. That would be a part of your job as an editor, is ensuring the rate of productivity. And does that rate of productivity limit the sort of stories you can tell? Like I would cite Miyazaki as someone whose work everyone loves, but the U.S. market is not really set up to support work of that scale, because it’s incredibly visually ambitious. Are we conceding that sort of reaching across demographics fantasy work to either TV animation or other countries because it’s just not economically effective for how the U.S. market is set up?

Obviously this is a whole thing that I’ve thought about throughout my career in publishing, and [something] everyone that I know who works in graphic novels is constantly thinking about. I know Nilah Magruder recently did an article about graphic novel speed and publisher demand versus that, and I can see all of the things that she said. As a publisher, you always need to think about artist’s times when conceptualizing how to publish a book. It’s so important to think about that and be really serious about taking care of author’s health so they can finish a graphic novel and continue to live a wonderful life with a body that continues to work so that they can finish a graphic novel and be excited about starting another graphic novel if that’s what they want to be doing next. There is that. That sort of thing is part of every initial conversation I’ve had with a creator I’ve been a part of both at First Second and at Random House. Talking about people, their deadlines, their process, and what they can make work.

As a publisher you want to make your schedule realistic for the author, and then the other side of that is you want to work with your retailer partners to make sure the books you’re publishing work for their schedule if you’re counting on sales from this particular account. So sometimes that means you have an author like Kazu Kibuishi, who is doing a big epic worldbuilding fantasy series that’s one of the best-selling kids' series on the market, and [doing] a book every three years, and sometimes you have an author like Dav Pilkey, who’s doing Dog Man, or John Patrick Green, who’s doing InvestiGators, who’s doing a book every six months. And when that latter thing is the case, when you’re looking at those tight schedules, as a publisher you have to think about the schedule but also how you can help the author with quick turnarounds from editorial, with coloring help, with lettering help, financially, all those things. And those books that are done in six months, I think those books are predominantly in the market category I think of as the seven-to-ten-year-old category. And they do have a simpler visual style than Miyazaki has, but I also think that visual style works very well for the market category it’s targeting, older elementary school readers.

While that is happening, I do think that fantasy is a wonderful and important category. I too love Miyazaki. And there are people like Ben Hatke, like Kazu Kibuishi, like Aliza Layne, whose Beetle & the Hollowbones just won a Stonewall Honor, like Natalie Riess and Sara Goetter, like Kat Leyh whose Snapdragon is amazing, like Tillie Walden, who does some of my favorite graphic novels, like Luke Pearson, who does phenomenal fantasy graphic novels. None of them-- I mean some of them are the North American Miyazaki, but Miyazaki’s on a mountaintop of his own. Part of the reason he has the prestige and esteem and awareness that he does is because he’s working partially in the comic space and partially in the movie animation space, and comics and animation aren’t set up in the same way in the U.S. as they are in Japan, which makes things different in terms of creator profile.

Do you keep track of an artist’s social media followers, and how does that work when your audience isn’t supposed to use those platforms?

The simple answer to this is no. As a publisher, I wasn’t paying attention to the number of social media followers an artist has. And that is as much to say that as a publisher, before signing up an author, I would say publishers generally do talk to an author, they look them up online, they might look at social media as part of that, but it’s more of “is this person going to be a good person to work with and a good fit for our company and the book they want to do for us, over this long-term process of making a graphic novel,” which is not to say that anyone is looking at “you have 100,000 social media followers and therefore you get an automatic book deal.” That research is more about an editorial personality fit. At First Second I worked in marketing and publicity and I think about marketing and publicity a lot, and there is an aspect of marketing and publicity [to being a publisher], but it’s more about how does a publisher make a book a success, and a publisher can’t rely on an author’s social media following to make a book a success. And they shouldn’t, in my opinion. Publishers need to have relationships with booksellers, they need to talk with teachers and librarians and directly with readers. And so a publisher might look at a person’s social media numbers and say “because this person has no social media accounts, this book is one we will have to make succeed by ourselves, and we can do that,” and I think that’s something a publisher needs to be able to do for their authors.

* * *

Wanting to speak to an author working within this space, I turned to MIKE DAWSON. Dawson has had graphic novels published by Secret Acres and Uncivilized Books, but in 2021, he released a middle grade graphic novel called The Fifth Quarter through First Second. The sequel, The Fifth Quarter: Hard Court, is scheduled to be released this July.

Brian: I wanted to talk to you about making work for a young audience in the book market, because you and I probably grew up as kids reading comics, but not for the book market, and probably a lot of things that a current adult would not think is appropriate for kids. One of the things you said on Twitter was you had an editor and most of her feedback was just to consider the audience, and I wondered how making kids’ graphic novels vs. making diary comics for people on Instagram, how does that affect your storytelling?

Mike Dawson: It was my agent who gave me the most advice about considering the audience. My editor didn’t say that so directly, but a lot of the editorial feedback had to do with storytelling, and whose story we were bringing to the foreground. And that’s a big part of how I approach something that is aimed at a middle grade readership, is to think about whose story we’re telling and whose perspective we’re showing. Because to me-- I have to caveat this as I mentioned right before we started recording, I had a book come out during a pandemic, I don’t really know the degree to which it’s connected with the intended audience. I’ve met kids in my town who’ve read it and seemed to like it, and that’s very rewarding, and I did have one opportunity to speak to a group of kids and they asked a lot of questions about the story. I think it’s connecting. But to get back to what I’m trying to say is I just considered it a constraint to be telling the story from the point of view of the main character who is a fourth grade girl playing basketball. While I, the types of work I do, I write about adults, human relationships, all the time, I just tried to put the stuff that has to do with Lori’s parents and other characters who are not the children, their story was just told through how Lori perceives it. And that’s really how I saw writing middle grade as, just to put some thought into whose story I’m telling and try to tell it from the perspective of that person, who happens to be the same type of person that you would hope would read the book. So, I just considered it a constraint, and I hope it works.

You’ve written stories before that were about kids, or about yourself as a younger person, without thinking about a youthful audience as who you had in mind. So does that allow you to be more digressive, or more unfocused or essayistic?

Two things. You mentioned before, about we, you and I, read books that were not aimed at kids. That were definitely not for kids. And I’ve written books like that. Troop 142 is a book that I published in 2011, and at the time it was maybe unclear to [the] readers I heard talk about it and to myself who the audience for that book was. I thought to myself that while I was writing with no audience in mind, I was writing in a pure way or something like that, but that’s not really true, because I’m writing in mind with someone like you and I, who I feel would enjoy that type of book. I’ve never written with no thought to the audience even though at one point I would have liked to think that I wasn’t. I wrote those earlier books with a thought to [who] I would like to read this, as a type of cartoon comic book fan, this type of comic book reader. I think it’s always something [that] I think about.

To the point of something else you talked about, about writing essays, I’ve written about children quite a bit from the perspective of myself as a middle-aged adult parent. I’ve written from the perspective of a father. That’s not what I’m trying to do with The Fifth Quarter. I did have to fight against some of my natural instincts, which would be to put the parents or the father more front and center and their point of view, and I did have to get that under control, because as much as I like to talk about my perspective, I don’t think a kid-- and the kids I’ve spoken to I can tell they don’t care about, they don’t want to know what the dad’s point of view is. It was revealing to me-- I had one experience where I was able to give a slideshow presentation to a group of fourth graders and it was revealing to me the parts of the story that clicked with them, and it really was the stuff about friends, and issues between kids who are in fourth grade, like copying each other, fighting, the bickering that happens on the playground, that was the stuff that really connected with them. Other parts of the story, like the mom runs for town council, and her emotions dealing with the outcome of that, I hope that the readers of this book will get something from the emotional payoff of that, but I’m sure they don’t care about the concept of town councils, local government. That’s something I’m interested in. But I’m hoping that presenting it from the protagonist’s point of view, her mother’s caught up in this thing that she’s doing and it’s pulling her away from what’s going in her life, I hope that part will resonate.

It’s funny, in terms of work for a general audience now, I always think about Pixar movies and four-quadrant storytelling, and there’s definitely a case to be made that this is maybe too much about projecting an adult’s anxieties onto kids and making movies they either can’t deal with or they care about other aspects of. And when I think of the classic kids' comics, I think of stuff like Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes, which were just in the newspaper and had a mixed readership. So what would influence you in terms of making work for children? What for you is a children’s comic you might’ve had in mind while you were working on this stuff?

I’m trying to think about that. I haven’t been reading a lot of comics in the past year. I’ve been reading a lot of novels. I probably had in mind to some degree the type of work I see out there in terms of middle grade but I honestly, and somewhat on purpose, didn’t immerse myself in what’s out there because I don’t want to be not writing like myself. So I really tried to not let the requirement that this be a middle grade book-- I tried to approach it the way I always approach writing, which is to think of different constraints. You mentioned talking about Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes as stuff that was maybe middle grade before there was a term for the category? Those cartoonists weren’t thinking about it. It didn’t really exist until 10, 15 years ago. So I’m trying to think of a good answer of what I was reading. I’ve read stuff since that I thought was very good in the middle grade category that probably will influence me as I go forward. Like I read a book called Shark Summer, which recently came out from Little, Brown. It was a very well-crafted story, it was well-plotted. It gave you that satisfying feeling of a comic well-told. And it made me feel good because that’s what I’d like to do, without feeling there needs to be any reducing the craft of writing just because it’s for a younger audience. I can’t answer too well in terms of what I was influenced by, besides trying not to be too caught up in what’s happening in that scene. Sorry.

No, that’s a good answer. What about, in recent decades there’s been more self-awareness in terms of child psychology and either what kids can take or what’s beneficial for a child to be exposed to. Is there any way you think about child psychology either in terms of your own children or looking back on your own childhood in terms of how characterization should be handled in a way that’s appropriate?

I used to work for a company that developed educational materials for children called BrainPOP, and I worked there for 10 years. I was drawing comics but also illustrating some content and building games. The general thinking among the writers I worked directly with was always that kids like to read up, not down. They always want to be exposed to things that are maybe a little bit beyond where they are. Like, this thing where you don’t need to simplify or dumb things down. The concept of thinking about the psychological impact of writing is not something I know much about. I have my own personal opinions. I have my experience from working for this company and other companies, I worked at Scholastic for a while so I know a little about trying to connect to children through day jobs. My personal experience is I had parents who exposed me to things that probably wasn’t appropriate for me to be exposed to. Like a movie called An American Werewolf in London, which I watched probably a million times when I was eight or nine years old. It’s gory, but it really sort of caught with me, I was somewhat obsessed with it as a child. My father put on a movie called O Lucky Man!, I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it. Malcolm McDowell, very surreal. There’s a part where a man’s head gets grafted onto a pig’s body and it has never left my mind.

But my feeling about it as a person, and then as a parent, is just that sort of stuff sparks something in people. I’ve always been shy with my own kids about putting things out there that might scar them. I’m not putting on crazy-bad stuff but I like stuff that’s a little dark. When it comes to characterization, I get the feeling-- this is very anecdotal, I get the feeling there’s usually more of a readership than an institution that’s decreeing this, but the readership doesn’t like characters that are doing negative, bad things. Like when the character is the person at fault and they’re not necessarily learn[ing] a lesson at the end of the story. I have parts in my book where the main character acts pretty badly on a number of occasions. You know, on a fourth grade level, but she’s the one who’s not acting right. She’s being jealous, she’s being mean, she’s hurting her friend’s feelings. I’ve received a tiny bit of feedback from some readers, lower stars on the Goodreads reviews because the character wasn’t acting right. Nothing you can do about that. But I definitely feel that it’s good to be presenting human nature in stories no matter who the audience is. I definitely feel like it’s good to show that everybody is not the good person all the time. That’s actually a valuable lesson to kids. And the book doesn’t have to end with the characters going “and I learned I shouldn’t have done that.” That’s just not the way people are, and I think it’s healthy if that can be depicted in kids’ fiction.

* * *

Thirty years ago, adult retailers functioned as the middlemen between the comics that were published and what children could access; nowadays, for bookstore market comics, librarians fulfill that role. BETSY BIRD is a former youth materials specialist for the New York Public Library who blogs for the School Library Journal. She is now collection development manager of the Evanston Public Library. I spoke with her to understand what librarians are looking for and how they meet the demands of their clientele.

Brian: Now you’re at the Evanston library, your title is Collection Development Manager. Before that you were at the New York Public Library. What’s the size of the client base?

Betsy Bird: I do it in terms of budget. Previously I had a budget of one million dollars a year to spend on materials, and here I have a a budget of about $700,000 to spend, which is still significant. But the New York library had additional funds they could give me as well, you’re dealing with 96 branches in a three-borough system. Here, I’m dealing with a town of 76,000 people. It’s different. One way I always used to describe it was at the New York Public Library I’d be like “Do I buy 200 copies of this book, or 400 copies of this book?” where here I’m like “Do I buy one copy of this book or two copies of this book?” And it’s the same process, it’s just the numbers are a little different.

At the New York Public Library you were specifically dealing with books for the under-18 crowd--

Well, children. I don’t deal with teens. So, 0 to 12.

I know the world of children’s books and book publishing is very strictly oriented in terms of age demographics it’s working with. How many different age categories are there essentially?

Three to four, I would say - it depends on whether you count baby board books among the categories, because that’s a whole different genre. Basically you’ve got your pre-K, your baby board books, your really really young kids, then you’ve got kids—which is 0 to 12, so board books kinda fall under there—then you’ve got teen, or YA, which is 12 to 18, then you’ve got everybody above that is adult. And in libraries it’s pretty striated. You’ve got your kids librarians, your teen librarians, and your adult librarians. So it’s really just the three categories over everything else. And at the New York Public Library we had two children’s specialists, for Brooklyn and New York Public Library, and then we had two teen specialists, and then we had just a mess of adult specialists.

In the graphic novel world of what book publishers are into, a lot falls into the “middle grade” and “YA” categories. I don’t quite understand the distinction. Middle grade is around 12?

It ends at 12, yeah. Middle school is where it begins to get really fuzzy. But it’s pretty easy. Children’s books don’t deal with blood, swearing, or sex. And teen books can. And adult books REALLY can. Teen books tend to be gentler than the adult books but they’re dealing with more complex subject matter, more complex thoughts and feelings. Romance tends not to appear in children’s books half as much as it does in teen. Teen really concentrates on that. It becomes nebulous. There’s no line. Except for children’s, some children’s things are clearly for children and no teen in their right mind would pick it up, whereas teen and adult, there’s a lot of crossover there. There’s a lot of adult titles that end up in the teen section, and a lot of teen titles that end up in the adult section. I mean Persepolis is housed in both sections, Maus tends to be housed in both sections, but there’s a lot of stuff specifically made for teens as well.

I guess that’s what I’m trying to understand the rules of.

Here’s where it gets simpler. The publishers set the rules. They’ll say right off the bat, this book is for this age category. They’ll say this is teen material, for 12-18. Or they’ll go by grade, they’ll say grade 9-12. Or for kids, they’ll say this is for kids 9-12 years old, or this is for grades 4 through 6. But the publishers set the age limit. The reviewers, to a certain extent, can challenge that and the librarians certainly can challenge that but generally when we’re ordering we’re dealing with so many materials we go with what the publisher tells us. So if they’re telling us it’s a teen book, that goes on the cart for the teen library. If they say it’s a kids' book, the kids librarian is the one who looks at it. They’re the ones who set the rules.

To me, YA seems like a genre. Because even though it can include all these categories, there’s a certain type of approach which is that it’s cleaner or less complex maybe. And then with the middle grade stuff, for kids, you’re trying to get kids to read. So to a certain extent, that involves humor or something, and then as kids get a little bit older it’s more about presenting work to them that relates to their lives, or that makes them feel a certain way about their place in the world. Is that accurate?

Yeah, I’ve heard that said before. Children’s books are very much about the adventure, the story, but once you get into teen it’s about identity to a certain extent. It’s about changing the world, it’s about injustice. Injustice reeeeeally comes into play in teen literature, way more than it does with kids. Dealing with the realities of the world, that’s sort of a teen thing, to a certain extent. So yeah, subject matter, but tone, a lot of it comes down to tone. It’s a lot darker in teen things. But not always, sometimes the teen things are really light and bubbly. This book Pumpkinheads [by Rainbow Rowell and Faith Erin Hicks] is straight-up teen but it’s the lightest most bubbly thing you’ve ever seen. You know, it depends on the book.

I’m thinking about kids' comics, where in the past there would’ve been newspaper strips.

Those are always shelved in the adult section. In [Dewey Decimal Classification] 741 for some reason, I don’t know why. Newspaper comics are a whole different genre. They’re completely different from graphic novels. We put a pretty strict line between the two of those. Your Calvin and Hobbes, your Peanuts, your FoxTrot, that is not necessarily-- now it’s beginning to integrate a little bit with your Baby-Sitters Club, your Bone, but generally there was a very strict line between the two of those in the past.

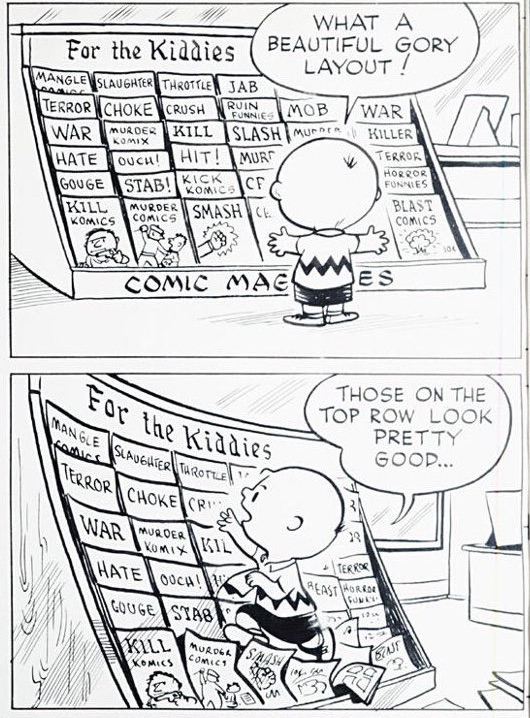

I saw a tweet recently that I have not been able to stop thinking about. A parent was showing their child Charlie Brown, and the kid was like “does he have depression?” and the adult says “yes.” The kid says “does he get help?” and the answer is no.

No. Like, [he] goes to a bad therapist. But yeah, no.

Something that’s funny or interesting about people making work for children now is there’s a greater understanding of child psychology.

And children have a better understanding of child psychology! I think that’s what that really highlights. A kid has probably been reading graphic novels where a kid goes to therapy at some point for depression, so they instantly recognize in Charlie Brown, “ah, same case!”

In your job, are you physically present within the library and meeting and interacting with people under 12, or no?

Ok, so I used to be a children’s librarian primarily. I worked with people under 12, up until about 2014. So 11 years or so, then I started being a purchaser and stopped working with kids, but now I do work the desk sometimes, I have my own kids, I interact with kids as an author, so I do have a lot of interactions with kids but not as much on the RA desk like I used to.

So what do you think is good? What are works coming in that you value? What are works that patrons respond to, and are they two separate things?

Of course that’s always the eternal thing with the librarian. The librarian wants the kids to have, as we say, “the rarest kind of best.” Here’s a link. Every year my library puts together the 101 Great Books For Kids and there’s a whole comics section in there. We’ve gone through a MASSIVE amount of graphic novels for 2021 and we have determined these are the best ones. Well, we didn’t say best, we say great. The kids have a very different interpretation of what they want. And this has always clashed with the librarians. The librarian is like “look! You should read this great work of literature” and the kid’s like “I want to read this!” It’s a little bit easier now that libraries are embracing comics where in the past they would’ve completely banned them from being purchased at all, especially in the children’s rooms. That was a long-standing prejudice. Now we have librarians who love comics and grew up with them themselves and that’s made a huge difference. And the quality of the actual comics being produced for kids is SO MUCH higher than it has ever been. The demand has been there consistently but the product just hasn’t met the demand. Now we’re beginning to see the product come out and meet the demand.

Of course that’s always the eternal thing with the librarian. The librarian wants the kids to have, as we say, “the rarest kind of best.” Here’s a link. Every year my library puts together the 101 Great Books For Kids and there’s a whole comics section in there. We’ve gone through a MASSIVE amount of graphic novels for 2021 and we have determined these are the best ones. Well, we didn’t say best, we say great. The kids have a very different interpretation of what they want. And this has always clashed with the librarians. The librarian is like “look! You should read this great work of literature” and the kid’s like “I want to read this!” It’s a little bit easier now that libraries are embracing comics where in the past they would’ve completely banned them from being purchased at all, especially in the children’s rooms. That was a long-standing prejudice. Now we have librarians who love comics and grew up with them themselves and that’s made a huge difference. And the quality of the actual comics being produced for kids is SO MUCH higher than it has ever been. The demand has been there consistently but the product just hasn’t met the demand. Now we’re beginning to see the product come out and meet the demand.

It’s so tricky, just the nature of the business, it can take you two years just to make a single comic and then a kid reads it in 15 minutes. It’s hard to meet that. But the books that the kids want and the adults like is becoming so much more aligned now, because the kids are getting really great stuff. I’m saying they’re trends, but these are like 10-year old trends, the Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Smile by Raina Telgemeier, these sorts of things kids love, adults also love. We had our first graphic novel win the Newbery Award, which is the award for the best writing in a children’s book-- that went to a comic, not last year, but the year before that. Jerry Craft, New Kid. People are really coming to love comics on a different level. But there’s still comics kids like that we don’t.

Can you give me some for instances?

Yeah, the series stuff, like Plants vs. Zombies. It’s fine. I don’t care. The kids love it, we get it. We have a challenge actually happening right now, and this is very serious, where a book we purchased-- there was no reviews, usually we like it if there’s a review. We make exceptions, and we made an exception where we really shouldn’t have. There’s a Minecraft YouTube series by these two personalities, they put out a graphic novel that’s an adaptation of this Minecraft world they’ve created, it’s called PopularMMOs, the first book was called A Hole New World, and it’s the most racist thing you have EVER seen! It is super racist, and we didn’t know. It’s a New York Times bestseller, it’s never been challenged, Common Sense Media says it’s fine, there’s no reviews, we bought it because a patron asked for it, and then another patron read it and said “uh, super-duper racist,” so we were like “what!” then we read it and were like, shoot. It’s super-duper racist, now we gotta figure out what to do with the darn thing. And it’s fairly popular because it’s about stuff kids already like. Video game-related stuff, LEGO-related stuff. A lot of these products [are] adapted into comics just because they already exist in another format, I’m not a huge fan of those. I mean, I love my Steven Universe, but I don’t care two bits about a Steven Universe comic, because it’s not how they began. Meanwhile, you’ve got really good quality stuff out there. So yeah, basically I don’t care about the commercial junk that people put out every other minute. I couldn’t care less. But the kids love it, so we get it. Sometimes it blows up in our face, as with the PopularMMOs.

Is there work you think is bad and then it turns out kids don’t like it or respond to it either?

Oh yeah, all the time. So I actually do buy the kids comics for my library. I don’t tend to buy many children’s things but I do buy the kids' comics because I have a lot of experience with that. And often I’ll get one of something if I don’t really like it. And suddenly we’ll get 500 holds on it and I’ll be like “argh!” Like “really, that’s what you want? Like really? Like really really? Ok.” And then I’ll buy more copies to meet the need. Generally speaking, the really popular stuff, I like. Except for like the Plants vs. Zombies thing, but even that’s not the most popular thing. The most popular things are all these memoirs that are coming out for kids. Now those Shannon Hale and LeUyen Pham Real Friends series, that thing, we can’t keep it on the shelves. To a certain extent, the Baby-Sitters Club adaptations. But you know, a lot of these personal memoirs done as graphic novels for kids. That’s the most popular stuff and I love them, those are great. Some of them are better than others but generally speaking the kids and I are on the same page.

So what would you like to see more of? Because my understanding is libraries are a huge purchaser.

You know, it’s funny there’s a publisher, C. Spike Trotman of Iron Circus, and I saw her speak, and she was like “look, I’m in the comic world, and people don’t know much about libraries. I tell them, look, you get your comics into comic book stores, and you know, there’s a lot of comic stores in the country, that’s impressive. You get them into libraries, and there’s way more libraries in the country than there are comic book stores. This is a market you need to reach out to and get to,” because especially right now, when everyone is so desperate for comics right now. What do I want to see more of, well that’s easy. I provided the link for the top books of the year but we had a huge struggle finding people of color in comics. Created by people of color, I should say. BIPOC. Because a lot of these memoirs tend to be white girls. I’ve yet to see a Black girl comic memoir. In fact, Black girls in comics in general, remarkably hard to find. Black boys a little more but not that many more. There’s just not a lot of Black kids in comics. There’s certainly not a lot of Latinx comics coming out. There’s not a lot of Asian-Americans, there’s not a lot of indigenous. There’s some, you get one, once a year, like yay! But, you know. Since the memoir comics are the most popular right now, and a kid comes up, says “I love Smile, what else do you have like this?” We want more like that. And we want more goofy diverse books. You know, Diary of a Wimpy Kid is hilarious, where’s the Black Diary of a Wimpy Kid? We want goofy, silly stories with a whole range of voices. In certain areas we do better in, in certain areas we got like nothin’. So that’s what we’re really looking for. If we can find that, oh, we will buy so many of those.

Is Evanston a diverse town? I don’t know anything about it. It’s a suburb of Chicago?

Evanston is the closest suburb to Chicago, we’re closely socially aligned with Chicago. We’re only 75,000 people. Compared to the other suburbs of Chicago, we’re the most diverse, but we’re nothing compared to Chicago itself. So our population is like 28% Black, I think we’re 5% Latinx, 5% Asian-American. So right now we’re trying to align our purchases with the census data, to reflect our population data, if we can. That’s just something we’re constantly working on. Regardless, every library in the country right now is trying to increase a wider range of voices on their shelves, regardless of who lives in their town. Because they’re like, it doesn’t matter who lives there, people need to see other people’s voices.

Do you have a sense of what kids who like to draw or are considered good at drawing by their peers like to look at?

Yeah, my daughter is a good example of this. She makes comics on her own. She hasn’t quite gotten to the age where she’d be posting them online. But she reads a lot of them on Instagram. There’s a lot of different online sites where kids get a lot of their comics. Sometimes they read the series, sometimes they go through Instagram. Not so much Twitter, they don’t really do Twitter much, they don’t really do Facebook much. I think there’s a bit of it on TikTok.

That seems wild to me, because it’s a video app.

That’s how they see their comics. Because they’re not getting the newspaper. When they’re on their own, they’re taking out their phones, they’re like ok, they’ve got their favorite people online that they follow, they’ve got their daily updates. You know, Instagram’s actually really good for that, I’ve found that to be the case. Like you can really get a good regular series going on there. That’s where they’re also sharing. My daughter mocks me because I use Microsoft Word and she’s like “why don’t you just work in the cloud all the time?” I’m like “yeah, that’s your people do that.” What she does, she creates her comics, puts them in the cloud, then her friends she gives access to can make comments, they can make edits, they can trade ideas. They work entirely online. She’ll make them by hand too, but she makes a lot of them through slideshows, the online slideshows. She loves taking Google Images, working them into comics, making her comics that way. You know, making animated slideshows so she can animate them to a certain extent. They find a way, that’s the zines of today. Like she will use paper for stuff, to show her theater friends, like “look I made a comic about us” but mostly she likes to take pictures of it, put it online and show them that way. That’s the preferred method.

First off, that’s a great answer, and super-interesting. But I should clarify I was asking a separate question, which is that I feel like, what a person who draws gets out of a comic is different than a person just reading it for the story. Like “oh! This is how I draw feet,” or something like that. I’m asking what younger people, looking at drawings in kids comics, are like: look at this, this is the thing.

Yeah, well, that’s YouTube videos, that’s TikTok videos. They get a lot of advice from, if they’re like “I don’t know how to draw feet, I’ll just go to YouTube and look up how to draw cartoon feet. Ok, I found like five videos about that. Ok, now I’m going to try that technique, I’m going to try that.” That’s what they do. They do get out books a little bit, and we do have books, how to draw cartoons, how to do manga, how to do anime, you know. Things like that. They go out ok, but that’s not really where the kids-- I mean the kids, YouTube, TikTok, that’s where they go for their info. They’re Googling it. There’s information online they can use, they’re saying that’s how I’m learning. It’s their go-to, so.

That makes sense. Is there anything I should’ve covered, that’s the more interesting part about the job or the larger culture, what am I missing?

I don’t know. I mean, the way that libraries buy materials is when they’re reviewed. Getting reviews for your materials is tricky. There’s only five or six review journals that we really look at. That’s School Library Journal, VOYA [Voice of Youth Advocates] to a certain extent, Kirkus, Horn Book, the Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books, Publishers Weekly-- these are the places librarians look when they want to buy stuff to avoid the problem we’re having right now with this unreviewed book. So, here’s where Iron Spike was telling us the problem. Comics artists work real last minute. They make the thing, the thing is in the store. There’s no long wait time. Review journals require things like six months in advance to review them. They want a really long lead time. That does not gel with the comic world. The comic world likes an instant “I’ve made it, it goes out.” And because of that, they don’t get the reviews. Because they don’t get the reviews, they don’t get in libraries. So, a rock and a hard place. Something’s gotta change here. Because if people want to get into libraries, they’ve got to work with the schedule that’s a lot slower than what a lot of people are used to. But it’s key for getting into large swaths of libraries. As is showing up for conferences, which we’re not doing right now because of COVID, but once we’re in person again, showing up for conferences, putting your booth down. I know a ton of comics artists who just started doing that and now they are known to libraries, they are in libraries. You’ve gotta get creative if you want to get into libraries, there’s not a single method of doing it, but there’s different things you can do.