It is one of the vagaries of an artistic calling that a person's entire career can come to be defined by a few key works, often created in their 20s or 30s, which for whatever reason somehow resonated with their audience. This has certainly been true of Garry Leach, who passed away in March this year. His early work on Marvelman with Alan Moore in 1982 remains the strip he is best remembered for, particularly outside the UK. This is perhaps not entirely surprising however, because few artists can have had such a varied, obscure and at times frustrating career as Garry. When I was compiling my Masters of British Comic Art book a few years ago Garry was the first person I contacted, hoping to get high resolution scans of his artwork. In typical fashion he was the last person to send anything in, fully 18 months later. I had mentioned to him that my principal reason for writing the book was to shine a light on the many great British talents who deserved to be better known, and that he was the person I was primarily thinking of. He simply would not believe me, no matter how much I tried to convince him, and felt I must be joking, which speaks volumes for his self-effacing personality. I wanted him to take his rightful place as one of the greats of British comics, alongside Bellamy, Embleton, Bolland, Burns and McMahon, whether or not he felt he deserved to be there.

It is one of the vagaries of an artistic calling that a person's entire career can come to be defined by a few key works, often created in their 20s or 30s, which for whatever reason somehow resonated with their audience. This has certainly been true of Garry Leach, who passed away in March this year. His early work on Marvelman with Alan Moore in 1982 remains the strip he is best remembered for, particularly outside the UK. This is perhaps not entirely surprising however, because few artists can have had such a varied, obscure and at times frustrating career as Garry. When I was compiling my Masters of British Comic Art book a few years ago Garry was the first person I contacted, hoping to get high resolution scans of his artwork. In typical fashion he was the last person to send anything in, fully 18 months later. I had mentioned to him that my principal reason for writing the book was to shine a light on the many great British talents who deserved to be better known, and that he was the person I was primarily thinking of. He simply would not believe me, no matter how much I tried to convince him, and felt I must be joking, which speaks volumes for his self-effacing personality. I wanted him to take his rightful place as one of the greats of British comics, alongside Bellamy, Embleton, Bolland, Burns and McMahon, whether or not he felt he deserved to be there.

Garry was born in 1954 and was, as he later wrote, “breastfed at an early age on Julius Schwartz’s DC science fiction titles”, though his enthusiasms also included numerous British, American and European comics and a wide range of fine art and cinematic influences. He spent four years studying graphic design at London’s prestigious Central Saint Martins art college, a period he did not remember particularly fondly as his tutors were unconvinced that comics were a legitimate art form. His first published work was created during this period, inking Trev Goring’s pencils on the digest sized Scorpio #1 in 1975, a comic he later remembered with a horrified shudder. He also supported himself by drawing short strips for DC Thomson, though if any were published, they have yet to be identified. He left Saint Martins penniless, but still deeply in love with comics.

His first work to make any impact with the public appeared in early 1978 in the short-lived underground magazine Graphixus, for which he drew several covers, posters and illustrations, along with a strip, and the comics’ logo. The strip itself, a 3-page self-written feature called "Succuba", was enormously impressive and revealed many of the elements that would come to typify his work: an innate understanding of anatomy; astonishingly detailed, delicate inking; high contrast lighting; an imaginative design sense; a futuristic setting; and pretty girls. However, prior to his Graphixus work he had already made a significant sale to a new British comic that was making serious waves among comic fans: 2000 AD. After leaving art school in 1977 he began working on samples for 2000 AD and made an immediate sale with a lengthy Dan Dare strip he both wrote and drew, rendered in sumptuous washes of grey paint. Since publishers IPC were not in the habit of letting their artists write their own strips, it’s likely that Garry created the whole strip himself and, realizing its quality, the editorial team then decided to buy it. The strip was published in 1978’s 2000 AD Sci-Fi Special, though his first work to appear in the comic was actually a short Tharg's Future Shocks strip in issue #58 (or Prog 58, as the comic eccentrically termed it) in April. These early breakthroughs were followed by a Death Planet cover (Prog 70) and his first inking assignments for the comic, working over pencils by Trev Goring and Dave Gibbons on Dan Dare (Progs 79-84) and Brian Bolland on Judge Dredd (Progs 94 and 95). He had arrived.

The following year was largely spent working for 2000 AD with a pair of solo Judge Dredd strips, another Future Shocks and a M.A.C.H. 1 strip for the 1979 Sci-Fi Special. Even at this early stage, though, he was already finding work outside comics creating adverts, illustrations and posters, something he would pursue throughout his career. In December, his first episode of a new 2000 AD series, The V.C.s, saw print in Prog 141, a space marines series loosely inspired by the Vietnam war which had been designed by Mick McMahon. Garry alternated with Cam Kennedy on the lengthy series, drawing 9 episodes over 8 months. It was to be his longest involvement in a strip as a penciller and firmly established him as a major force in 2000 AD. Garry had been one of the last of the first generation of 2000 AD artists to join the comic, and the last to make an impression on the readership beyond just being an inker. The V.C.s allowed him to finesse his artwork with action-packed storytelling and more focused, controlled inking. It was also notable, however, that Cam Kennedy was drawing twice as many episodes, evidence of just how slow Garry was becoming; this was to be the only regular series he was ever given at the comic. Other British jobs that year included his interpretations of DC characters for Superheroes magazine and the Wonder Woman Annual, alongside a cover for that year's Lion Holiday Special, a last gasp of IPCs traditional weekly comics that 2000 AD was throwing aside.

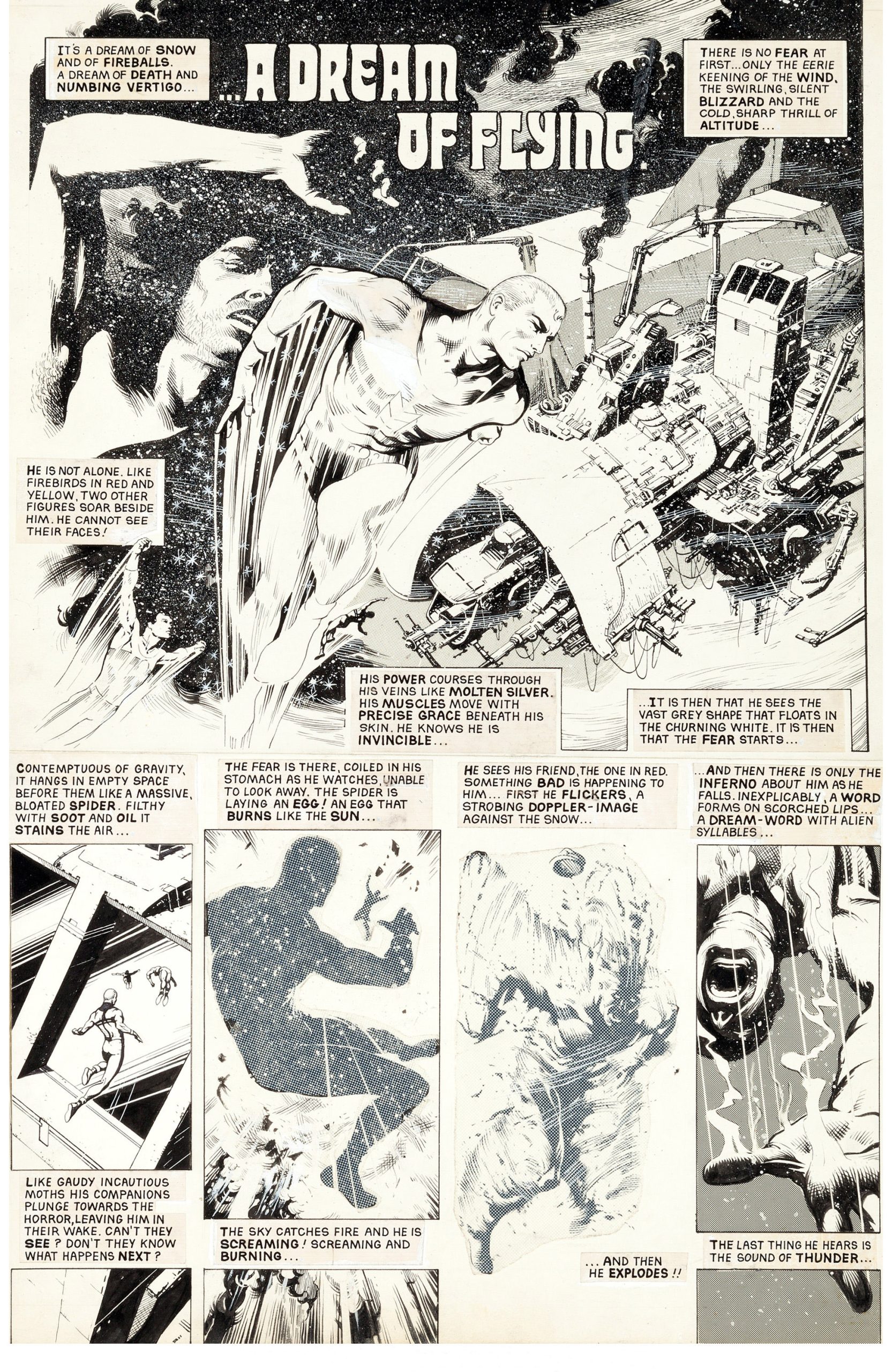

For much of 1980 and '81, comic fans would have looked in vain for new work by the artist, but every few months a new Future Shocks strip would appear in 2000 AD reminding them of his talent, each one more beautiful than the last. Altogether he drew seven of these short strips, including one for the 1982 Starlord Annual. By far the most momentous of these was a beautifully quirky 4-page strip called "They Sweep the Spaceways" in Prog 219... written by a new discovery, just beginning his career, by the name of Alan Moore. Eight months later, comic fans were amazed to discover a new monthly comic magazine at their newsagents by the name of Warrior, from a new publisher called Quality Comics, which had seemingly come out of nowhere. It is no exaggeration to say that Warrior—and particularly its two series written by Moore: V for Vendetta and Marvelman—was a giant leap forward for British comics. Even in an artistic lineup that included David Lloyd, Dave Gibbons, Steve Dillon and John Bolton, Garry’s work stood out, marking a quantum leap in his abilities as an artist, announcing him as one of the finest in the industry.

Marvelman was a re-imagining of an obscure 1950s Miller Comics superhero, itself a somewhat juvenile re-imagining of the old American Fawcett hero Captain Marvel. Alan Moore’s great innovation was to reposition this simplistic hero in a more naturalistic, realistic world. Garry’s art had always been intrinsically realistic, but his work on Marvelman took that to new levels, with acutely, subtly observed figures in perfectly realized settings to create a wholly believable, contemporary world. He could also summon up scenes of wonder and dynamism, with beautifully staged fight scenes rendered in meticulous detail, with sheets of mechanical tones and minutely textured backgrounds creating imagery of astonishing depth. Warrior’s other great innovation, beyond providing a venue for this new, mature approach to comics, was to offer their creators ownership of their work, though this was counter-balanced by a far lower page rate than anywhere else in the industry. The theory was that these strips could be syndicated around the word and collected into books, bringing in far more money for their creators than a standard page rate. However, Garry was taking more than a week to draw each page and found he was simply not earning enough money to live; after drawing four episodes, and inking his replacement Alan Davis on a further two, he left the series.

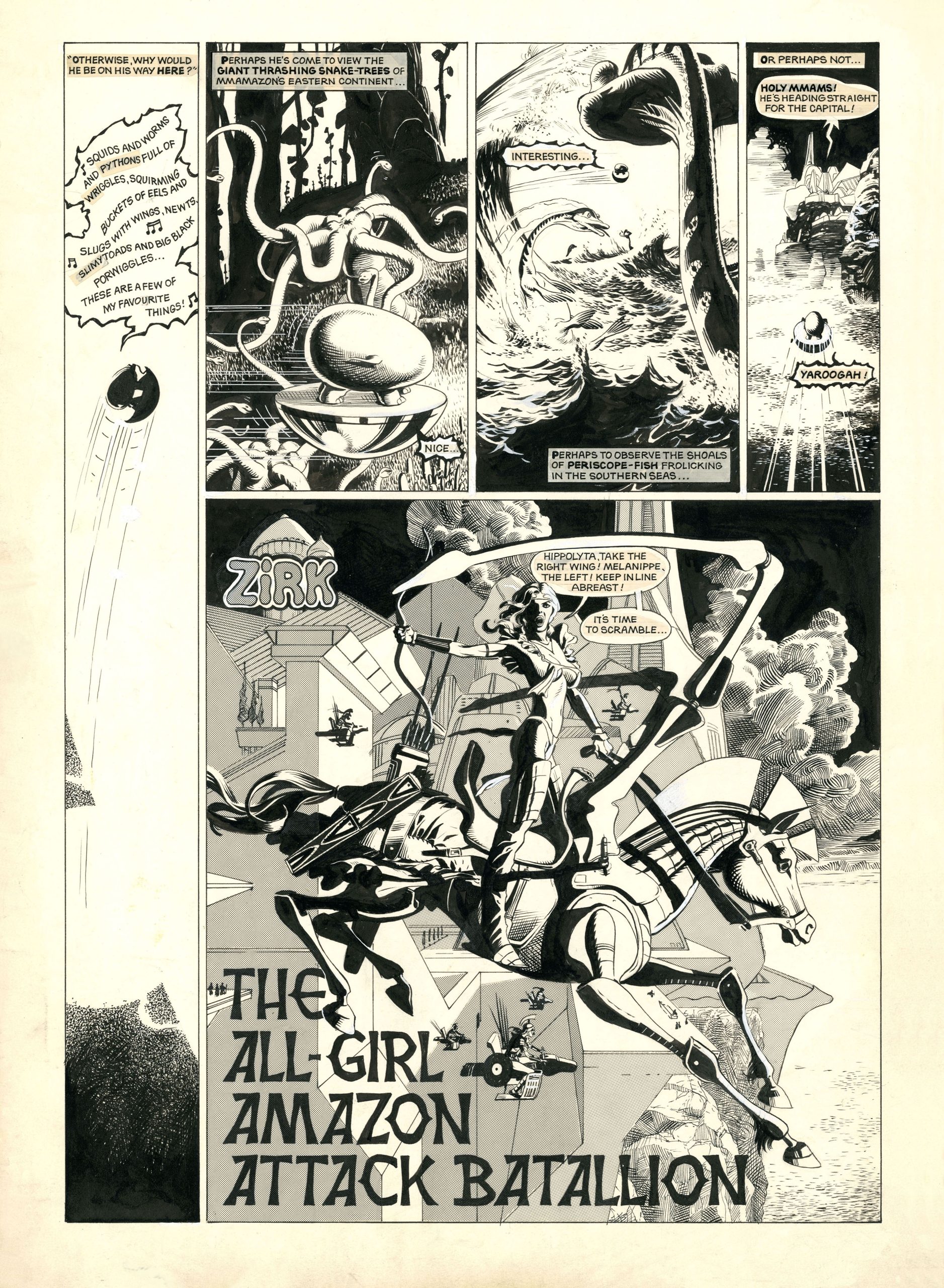

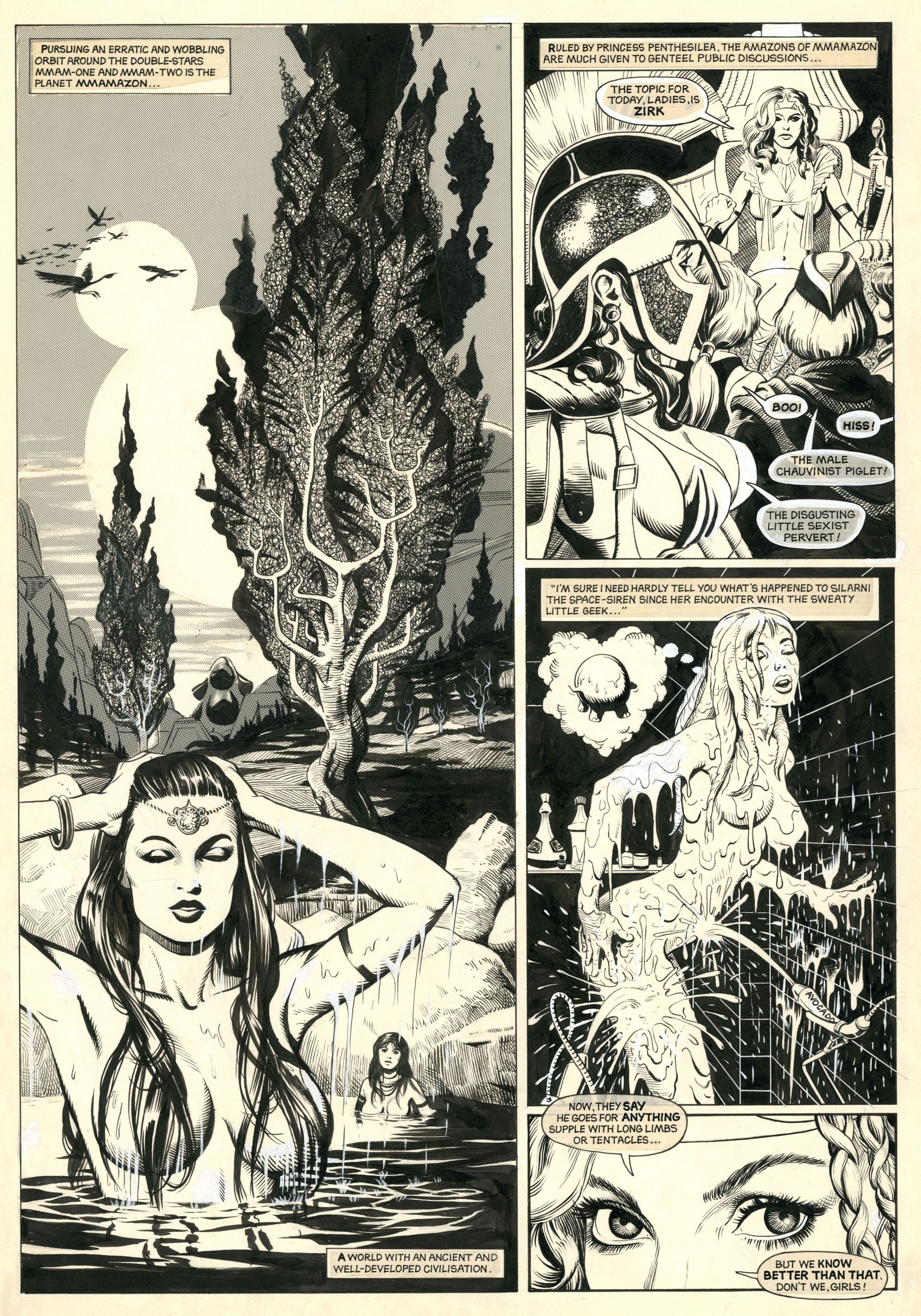

Garry’s involvement with Warrior went far beyond simply being one of its artists. From the beginning he worked on its design, created covers and provided illustrations so that even after he had left its flagship strip he was always a visibly integral member of the team. In issues 9 and 10 of Warrior he and Moore presented a cerebral new science fiction feature tangentially tied in to Marvelman called Warpsmiths, which imagined a sumptuously designed alien universe. Moore had also written a third episode that remained undrawn for a further six years. Garry next moved on to an entirely different sort of strip, starring a thoroughly reprehensible egg-shaped alien from Warrior's Laser Eraser and Pressbutton series: Zirk.

"The All-Girl Amazon Attack Battalion", written by Steve Moore (as Pedro Henry) in Warrior #13 was perhaps Garry’s single greatest strip as an artist, with none of the subtlety or depth of his Alan Moore collaborations, but with all of the elements he loved to draw: alien worlds, bizarre creatures and lots and lots of pretty girls. By this point his exquisite figure work was fully realized, with an assured, relaxed subtlety that only the very best artists can attain. Each panel was also perfectly composed, with carefully juxtaposed layers of line, tone and shadow to create imagery of great depth and clarity. His friend Dave Elliott recently suggested that Zirk was precisely the sort of strip Garry would have been happy to draw for the rest of his life, and in many ways it provided a template for much of his later work. However, it also marked something of a turning point in Garry's career, where he would have to move away from regularly drawing strips because his increasing perfectionism ensured they could simply never pay enough to support him.

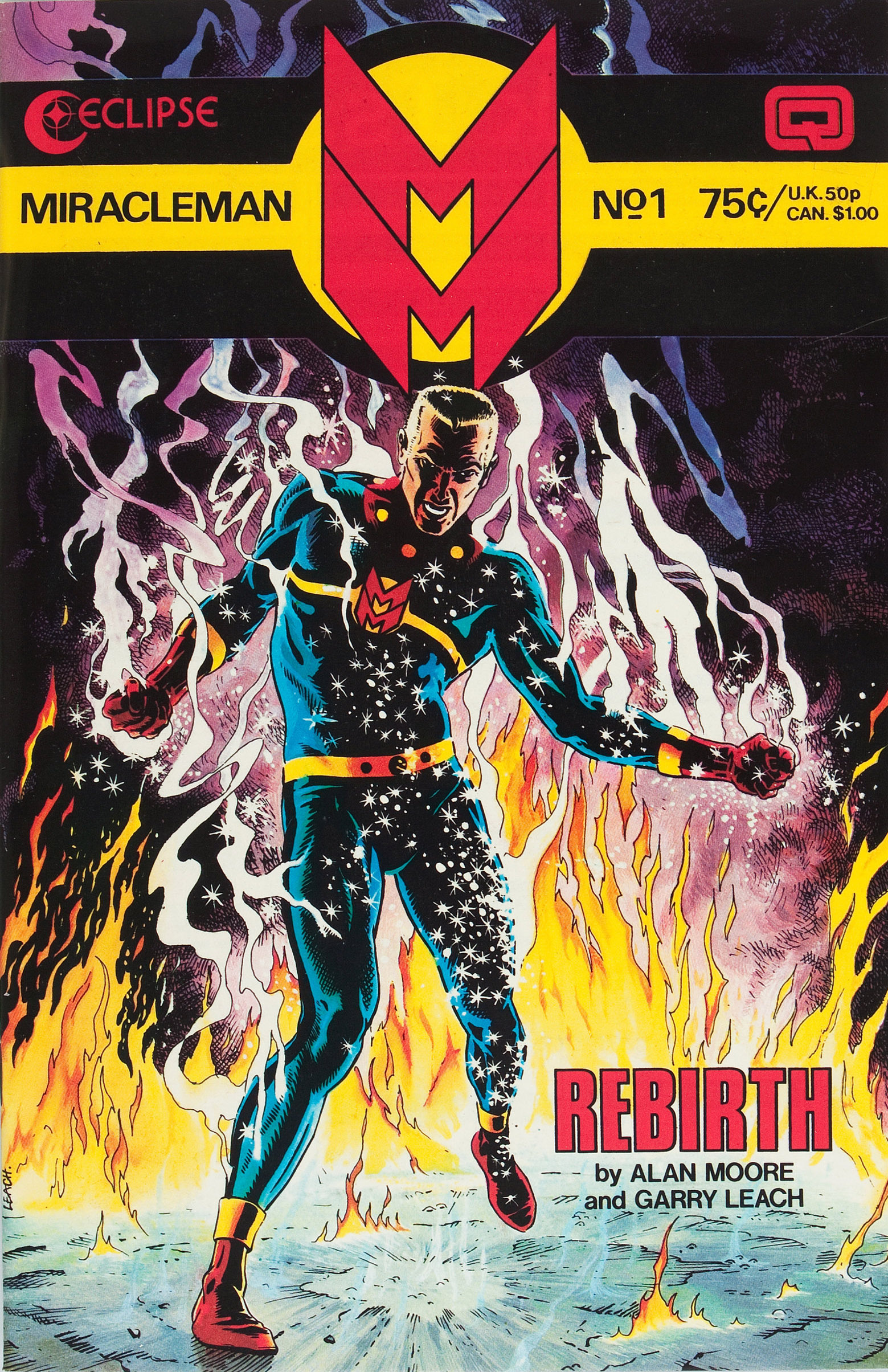

With issue 15, Garry became Warrior's art director, though he continued to have a notable presence in the comic, contributing logos, illustrations, lettering and five brilliant covers, alongside more work for Quality’s relaunched Halls of Horror magazine. Warrior was cancelled in early 1985 after 26 issues, but by that point it had already begun syndicating its strips around the world, including an agreement with Eclipse in America which reprinted first Pressbutton (as Axel Pressbutton) and then Marvelman (by that point rechristened Miracleman due to legal pressure from Marvel Comics). Garry provided covers, production work and some colors to these reprints, including a radically altered version of Warpsmiths which translated the tonal richness of its b&w artwork into glorious color. The Miracleman repackaging proved to be less successful, with the black and white original version far more satisfying, though few American fans would have had the chance to experience it. A second Pressbutton series (Laser Eraser and Pressbutton) from Eclipse featured entirely new material created exclusively for the American market, which included one issue (number 3) inked by Garry over pencils by his friend Jerry Paris, which hinted at a US inking career to come.

By the mid ‘80s, seemingly every notable British artist had been enticed over to American comics with the promise of their own miniseries, prestigious Annual, cult '70s revival or ground-breaking prestige project. Except Garry. Or at least, if he had been offered anything, he chose not to take it up. For those waiting to see what he would do next after Warrior, his work would be spread far and wide. Commissions in the second part of the '80s included 10 covers for Eclipse, including obscurities like ESPers and 3-D Laser Eraser and Pressbutton; 5 covers for Quality’s line of American-format UK reprint comics; 8 covers for DC, mostly for the Legion of Super-Heroes; inking Jerry Paris on an obscure back-up strip in Captain Britain Magazine #4; inking an even more obscure back-up strip in Lodestone’s already-obscure Codename: Danger comic; artwork for badges; fiction illustrations for British Annuals; artwork for his local comic shops; abandoned t-shirt designs and 3D advertisements for the Action Force toy line. His only American penciling job in this period was, true to form, an obscure eight-page Dream Girl back up in Legion of Super-Heroes Annual #4 which seemingly went mostly unnoticed. His strangest assignment was surely inking an unpublished Marie Severin strip for the Marvel UK ThunderCats comic (issue 83, 1988), taken up simply because it seemed like fun.

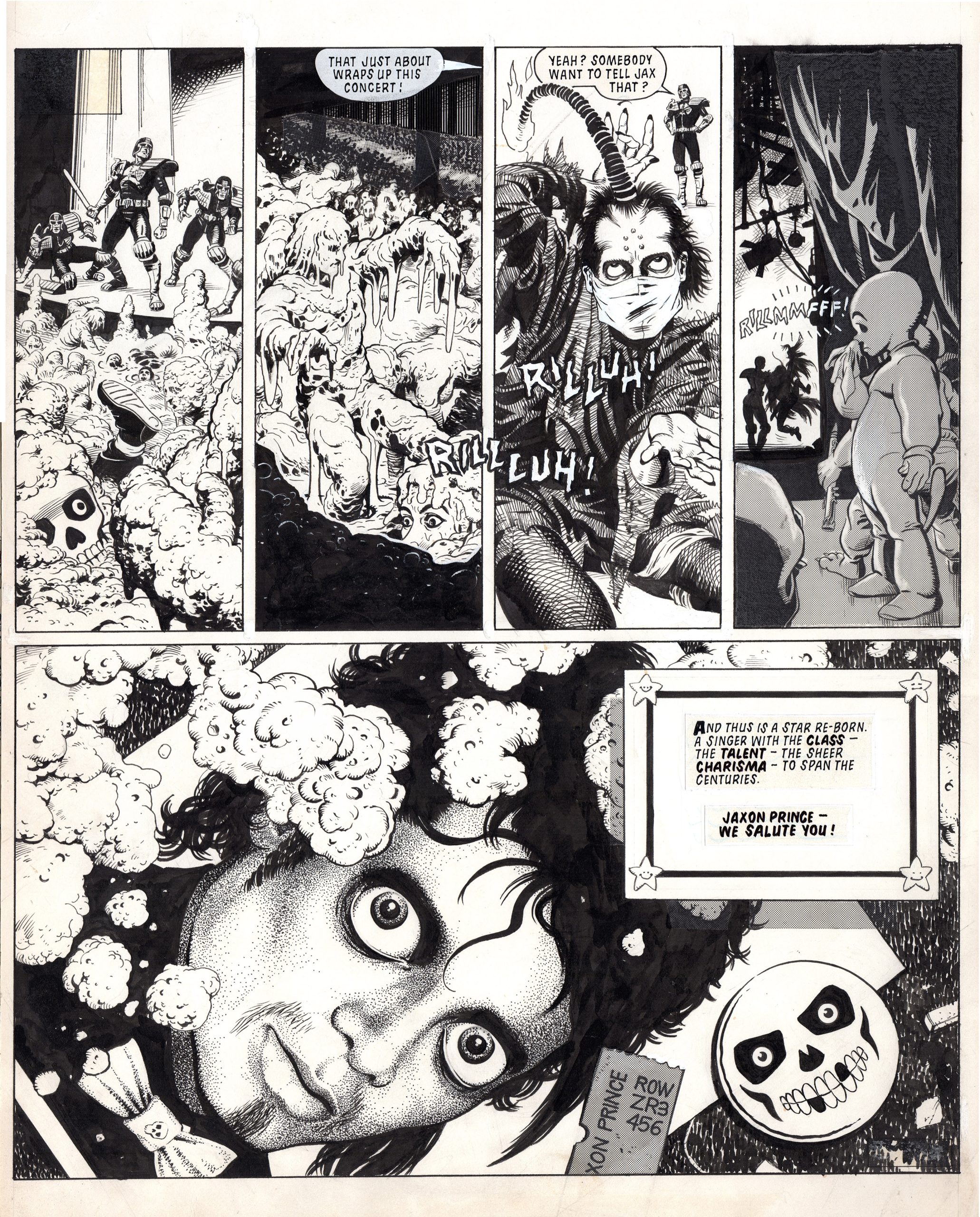

However, three years after Garry's last Warrior strip, British fans were at last able to enjoy his full art work again when he returned to 2000 AD with one of his finest Judge Dredd strips: "The Attack of the Fifty Foot Woman" in Prog 492, published in late 1986. This was quickly followed by two more classics: "The Comeback" in Prog 513, starring a thinly disguised Michael Jackson; and "Ten Years On", in Prog 520, all of which established Garry as one of the definitive Dredd artists of his era, on par with Brian Bolland at his best. "The 50 Foot Woman" strip in particular was immensely inspirational to the new generation of 2000 AD artists just coming in to the comic as the original creators moved on. I know, I was one of them.

But as ever, Garry was struggling to work quickly. He devised a cunning plan: he and Dave Elliott would adopt pseudonyms (Paul Behrer and Spud), which would somehow trick themselves into becoming faster artists. Garry would paint the opening double page spreads of each Dredd episode on which the two would work, and then lay out the remaining pages which Dave would finish. Maddeningly, even Garry’s layouts proved to be slow to work on, so another artist friend, Will Simpson, was brought in for pencils. Ultimately the group produced 3 episodes of Judge Dredd’s sprawling "Oz" saga before Dave and Will continued on without Garry’s involvement. Away from Dredd, Garry created some of his most memorable artwork for 2000 AD with a pair of beautiful painted covers (for Prog 561 and the 1987 Summer Special) and four back cover pinups of the Dark Judges. He also created work for a serialized Sláine role playing game, while for Titan books he crafted five covers for their The V.C.s and Judge Anderson reprint books. Those two years of 2000 AD-related work rivaled his Warrior period for quality and inspiration.

As the '90s approached, Garry and Dave Elliott made an unexpected move into publishing under their Atomeka imprint with A1, a square bound anthology aimed at the American market which picked up the mantle from Warrior and featured continuations of many of its strips. Over six issues and one True Life Bikini Confidential special (running from 1989 to 1992), A1 published memorable work from many of the top talents in the industry on both sides of the Atlantic. As co-publisher, co-editor and art director, Garry’s time to draw was limited, but he still contributed two fantastic strips, both illustrating unpublished scripts from Warrior: the much delayed third Warpsmiths episode in A1 #1; and a lascivious Zirk strip in the Bikini special. The Warpsmiths strip in particular (and its attendant cover) was if anything even more precise and tonally dense than the previous Warrior episodes, and must rank as one of his finest achievements. Atomeka published several more specials before Elliott moved on to Tundra; subsequently, Garry created very little comic related material for the rest of the '90s... with one notable exception.

Garry’s fellow Graphixus artist Nick Neocleous recalled a meeting they had one time: “I asked him once why we didn’t see more comic work from him. He told me he was doing lots of advertising and film work. He said he could do one illustration and get 10 or 20 times what a comic page would pay. He loved comics but chose a more economically viable direction.” These commercial jobs in the '90s included artwork for Kellogg's and Nabisco breakfast cereals, while both Garry and his partner, Una Fricker, become accredited Disney artists. He could also be seen regularly in the venerable British listings magazine The Radio Times, and painted multiple Magic: The Gathering cards for the Seattle gaming company Wizards of the Coast. There was artwork as well for BBC Worldwide's unpublished Robot magazine. It was a productive time for him, though this mostly resulted in work that his fans weren’t aware of.

The one time Garry was tempted back to comics in this period was for work in Penthouse Comix, whose first editor, George Caragonne, was a great fan of his art. What Penthouse Comix lacked in subtlety or restraint it made up for with a hefty pay rate which enticed many of the industry’s top creators to work for it. Garry drew two strips (in issues 1 and 3) and inked two more, also contributing several covers and illustrations. By far the best of these commissions was his first strip: "Bethlehem Steele", a gorgeously-drawn space opera which mixed explicit sex scenes with his distinctive science fiction iconography, making it look in places startlingly like an unusually racy episode of Warpsmiths. Garry drew one further strip for Caragonne, a short T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents story while the editor was under the mistaken belief that Penthouse had the rights to the franchise. When this mistake became embarrassingly apparent, several whole issues had to be abandoned, and Garry’s strip remained unpublished until IDW's 2015 T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents 50th Anniversary Special.

Dave Elliott has suggested that Garry rarely sought out comic work, with most of his assignments coming from friends or admirers who wanted to work with him. This goes some way to explaining his prolonged absences from the art form, and also his return to mainstream comics in 1999, starting off a lengthy period of inking strips drawn by British and Irish artist friends. Indeed, for a generation of American comic fans, he is possibly best known as John McCrea’s inker at DC Comics, collaborating on 37 issues of Hitman (23-30, 32-60), 1 issue of The Authority (21) and its 12-issue spinoff miniseries, The Monarchy. Other work from this prolific period included two further issues of the Authority inking Chris Weston (issues 17 and 18), and several for Marvel: Howard the Duck, inking Glenn Fabry (MAX series, issue 3); and X-Men: Millennial Visions (2) and Spider-Man: Get Kraven (6), inking McCrea. Elliott has spoken about Garry’s inability to be decisive in drawing strips, constantly revising and redrawing layouts to the edge of deadlines and beyond, but inking is a different discipline. Coming to a page as an inker, most of the decisions have already been made, so one’s contribution is about line strength, tonal balance, finessing and, occasionally, refining the drawing. For a craftsman like Garry, he was able to bring so much to each job without the pressure of producing a great “artistic statement” every time and, perhaps most importantly, for once he could meet his deadlines. Though again, perhaps inevitably, the perfectionist in him couldn’t help repositioning or “fixing” certain panels he felt weren’t working.

Looking back at his career, fellow Warrior artist David Lloyd suggested that “Garry was great but he was slow through his painstaking artwork, and this business has no patience with that in the generality of things. In some ideal circumstance of past possibilities, he'd have made enough of a long-lasting impression to have a strong industry rep and then get to work on a long story that he could take time on and make a fabulous thing of that would elevate him to much higher status. In that absence we have fabulous short things instead, which are nothing less artistically but are less than what we all could have seen from someone who saw the value he could get from every panel and did his finest to give it to us.” Garry’s inking provided him with a large enough wage to live on, and no doubt was satisfying in its own way, but there is always the regret from his fans that he was never able to earn a living creating his own strips.

In 2002, unexpectedly, Garry popped up as the artist for the first issue of Wildstorm’s Global Frequency comic; at 22 pages, it was the longest single strip of his life and a reminder that he was still a fantastic artist in his own right. After this, however, his comic work became far more sporadic and obscure with years going by with little more than the occasional cover to remind us that he was still active. One short-lived assignment was strip work for four issues the little-known Sorted magazine in 2004, for which he insisted on using a pseudonym. His inking and art assists could be found in comics like Kinetic, Judge Dredd Megazine, Shark Man, The Twelve, Marksmen and Freedom Formula, working with friends such as Rufus Dayglo, Chris Weston, Steve Pugh and Warren Pleece. One tenacious champion was writer Garth Ennis, who brought Garry in to create covers for a number of his series at Dynamite, Wildstorm and Virgin, including Battler Britton, Battlefields, Dan Dare and The Boys. Garry’s versatility was evident in the extraordinarily assured aviation paintings be created for many of these titles, evoking memories of the great British war digests generations of Brits would have grown up reading. Perhaps his most visible comics work of the 21st century came when Marvel unexpectedly released a repackaging of Marvelman (once again retitled Miracleman) with newly-colored reprints from Warrior, including Garry's Warpsmiths strips; the artwork was also restored by Garry. He was even brought in to create a typically gorgeous cover for issue 14, though no further work appeared.

One enjoyable side-line for artists can be the growing number of private commissions for fans, which allows even the slowest creator to really express themselves - Garry was no exception. These commissions typically fell into 3 categories: Marvelman; pretty girls; and classic Marvel and DC Characters, all of which he excelled at. Indeed, some of his commissions were even more polished and accomplished than his best comics work. His ability to mimic vintage Golden Age artists like Dick Sprang and Curt Swan was extraordinary. But Garry increasingly seemed to withdraw from visibility, and while I was putting my Masters of British Comic Art book together, I was often asked about Garry. For some he had become an almost mythical figure, with admirers wondering what he was doing, or even if he was still alive. Visitors to his favorite London comic shops could often see him chatting with friends, but he attended fewer and fewer conventions, and the only mainstream comic work in the last ten years of his life was the aforementioned Miracleman cover and an obscure incentive strip in a crowdfunded graphic novel project, The Liberty Brigade. In fact, in the four decades after Warrior closed down, Garry had only drawn thirteen comics, and few of those were more than 6 pages long. He remained active away from traditional comics, however, particularly through working with his friend and admirer Dave Elliott. Some of his last work appeared in a series of non-fiction graphic novels from Zuiker Press, edited by Elliott with Garry providing inks: Click and Mend (both published 2018) were followed by Imperfect and Colorblind (in 2019), written by young people for their peers.

Aside from his brilliance as an artist, Garry was also a very special person, as his friend Dave Elliott explains: “Garry was the UK's Comic Laureate before Dave Gibbons, albeit in an unofficial capacity. I've never known anyone for giving his time, patience, and effort to any who asked it of him. Garry would give fans his phone number and email address and would coach them, whether it was to become a writer or artist, for as long as they needed him. He'd do the same for store owners and their staff. He helped with dozens of events at Orbital Comics, producing posters, banners, art, and organizing events. He did the same for the Northern Ireland festival in Derry. If he could have made a living at doing this he would have been as happy as a pig in shit. Something else that separated him from a lot of comic creators I know, Garry never stopped loving comics. He LOVED going to comic shops and talking comics to everybody before buying his stack and taking them home. Garry never tired of that aspect of the comic business. New Comic Wednesday was his favorite day of the week. When we started A1, Paul Hudson's Comic Showcase became an extra office for us. We'd keep spare stock there and then have our editorial meetings in Frank's Café about five doors down. Several coffees and bacon sandwiches were demolished while we went through several iterations of the next issues paginations. The best way to get Garry to meet you was to meet in a comic shop on new comics day.”

It is almost impossible to plan a career as a freelance artist, particularly for someone as painstaking as Garry, and it can be frustrating for those who admired his artwork that he was not able, or willing, to create more of it; but both his art and his life were unique, inspired, and brilliant and that’s worth treasuring and celebrating.

* * *

With thanks to Dave Elliott, David Lloyd and Nick Neocleous.