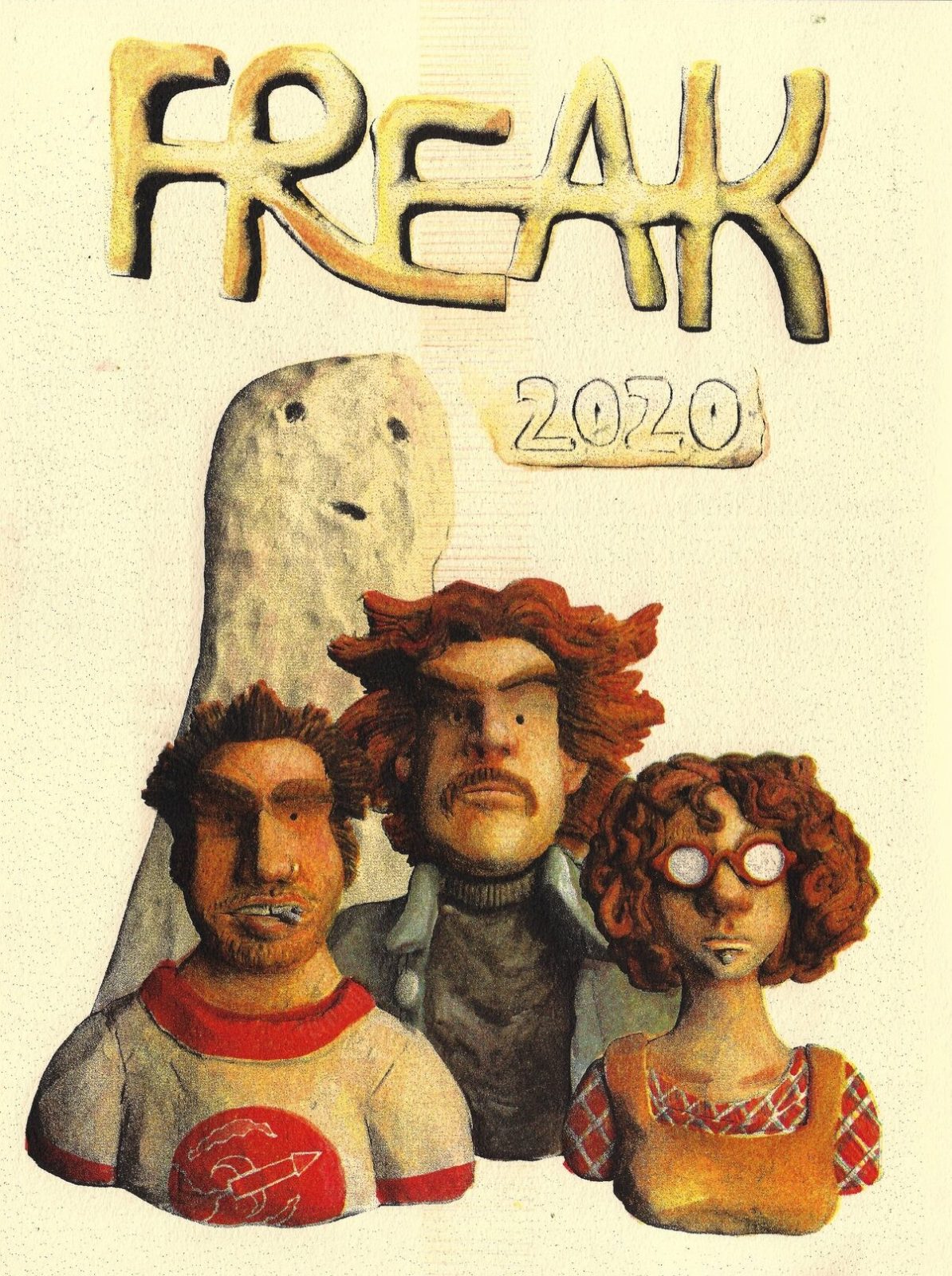

The Freak Comics Collective formed in 2018 while the three members all attended the San Francisco Art Institute. Since their initial meeting, they have gone on to put out 10 issues of their flagship Freak anthology plus several publications by each member. Cristian Castelo’s coming-of-age stories place a hearty emphasis on spot blacks, lively lettering and overall dynamism. Mara Ramirez’s work focuses on the land and sea, and their hazy pencil work perfectly captures the ephemeral emotions of memories and dreamlike states. Miles MacDiarmid is master of character design and setting. Like a great multi-cam sitcom, MacDiarmid is able to give each member of his vast cast the spotlight while also incorporating his unique sense of utter chaos. Freak has recently branched out and published the first standalone book by someone outside the three founders - Oboy Comics by Shaheen Beardsley. Oboy, about a meandering degenerate superhero, would immediately gross out any reader if Beardsley’s line wasn’t so damn pleasing.

In short, Freak is the present and future of comics. We discussed their individual work, current publishing endeavors and Freak’s mission statement.

-RJ Casey

* * *

RJ Casey: I just came across a video while doing my hard-hitting research of you trying the Flaming Hot Cheetos Mountain Dew.

Miles MacDiarmid: I did try it.

I need the verdict.

MacDiarmid: It tastes pretty good. It tasted like a normal Mountain Dew except that it’s kind of spicy in your throat and since it’s a drink it goes right down into your stomach. Then you just have hot tummy.

[Laughs] So, no good?

Cristian Castelo: So not good.

MacDiarmid: It’s ok. It’s ok. It’s worth trying. If you come across it, you should buy it.

Mara Ramirez: Miles is on tour right now which is a really good thing for him because he gets to try out all the novelty drinks and snacks.

MacDiarmid: And that’s why I’m currently drinking coffee out of a 40-ounce container.

[Laughs] I guess we should transition this into comics. How did all three of you meet originally?

Castelo: I was at the bar and it was a really crowded day. Then Mara walked in and didn’t have anywhere to sit. Mara was like, “Is this seat taken?” Then we started chatting and then Miles walked in and he didn’t have a place to sit either, then he sat with us after he asked, “Hey, is this seat taken?” Then the three of us found out we all liked comics and the rest is history.

Ramirez: If you’re going to make a joke, you’ve got to make it funny. [Laughter]

MacDiarmid: I was hired to make a hit on Cristian and kill him but I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t pull the trigger. His face was so precious and I just gave him a little kiss on the forehead and said, “I know someone who also loves comics. Let’s get together.” [Laughter]

Ramirez: Is this being recorded?

It is. [Laughter]

Castelo: We went to San Francisco Art Institute. They were two grades below me. I was graduating that year - this was like 2017. Our school didn’t have an illustration program. We had printmaking and that’s the closest thing, so all the illustrative people would do that. Nobody was really doing any comics until my last year there, unfortunately. These two and I connected over that. We went out for drinks one night and talked about loosely making a comic collective. It was a drunken, “Yeah, let’s do it.” And we kind of did it.

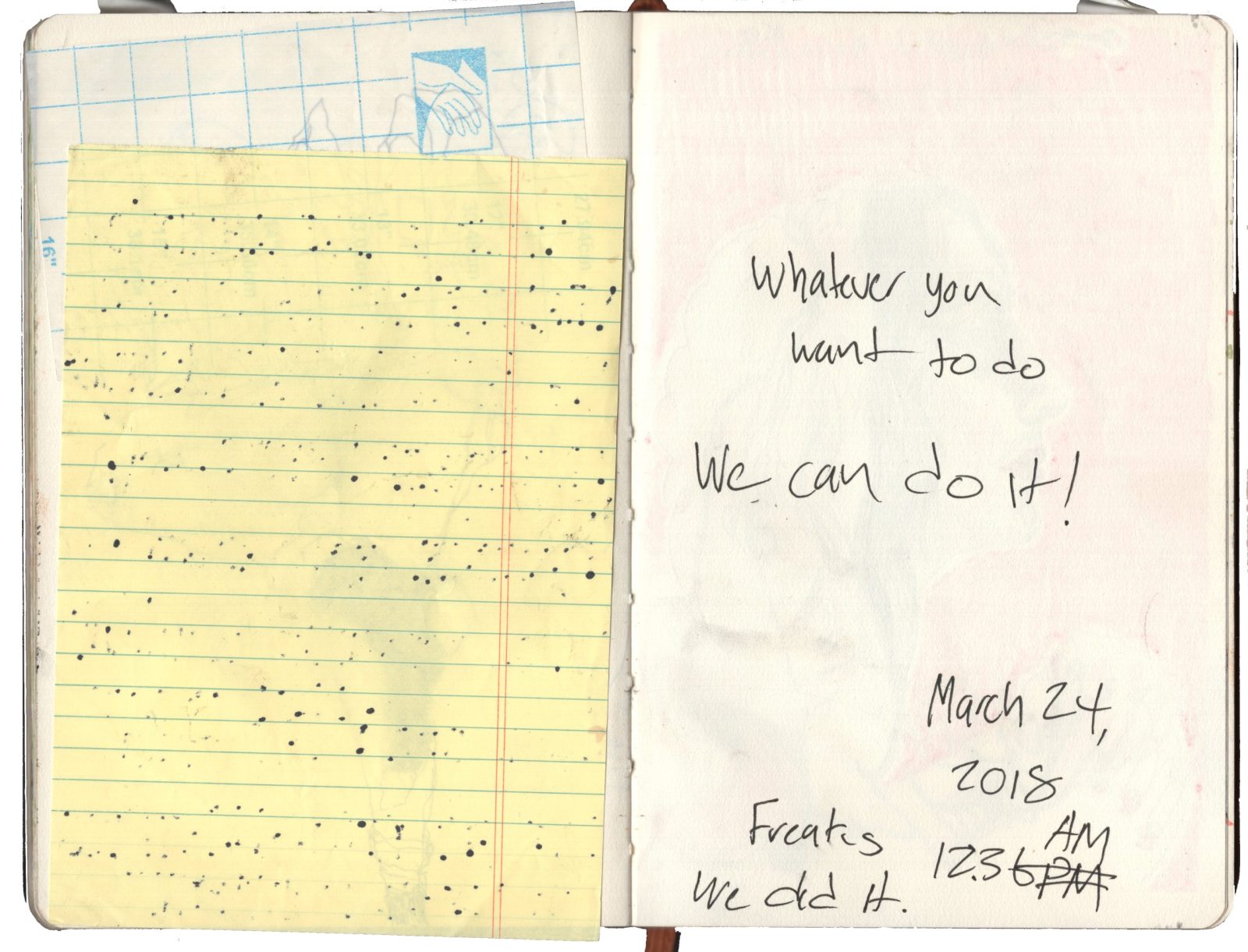

Ramirez: I remember the conversation. I found this Xerox machine at Goodwill that week and I was really jazzed. I was a big zinester and was really excited about that. During that conversation I was like, “I have a Xerox machine! We have to figure out how to help people make zines.” It’s fuzzy, but I do have a page from the sketchbook I was keeping at the time. We were all drawing together too and it says, “We did it! Freaks!” and the date. I think it was March 17, 2017. I’ll find it.

MacDiarmid: It says, “We can do it!”

Ramirez: I think that’s right. [Laughs.]

MacDiarmid: The day we can’t do it anymore we’ll scribble that out.

And you all agreed on the name Freak Comics?

Ramirez: That night, yeah.

Are you all from the Bay Area originally?

Castelo: They’re both from Santa Rosa.

Ramirez: Well, Miles grew up in the Mission. I was born in Daly, but grew up in Sonoma County. We were all in like a 100-mile radius. Miles and I met at Santa Rosa High.

How has the Bay Area affected your comics making? You’re part of a storied lineage there.

Ramirez: I think that was part of our first conversation that night. Where I first met Cristian was in a class called “Gentrification”. The first time I remember noticing him was him loudly sighing. [Laughs] We just talked about the techie dudes in backpacks at the Daly City BART station. I was like, “Yeah. I feel you.”

Castelo: I remember there being a twirly-mustachioed man one day in my neighborhood that wasn’t there before. I was like, “ok, this is what’s happening.”

Ramirez: We were talking that first night about how the Bay’s pushing artists out constantly. It’s a really hostile place for poor people. It’s extremely, extremely expensive. Me and Miles lived in a studio apartment with one tiny little window, a minifridge and no bathroom. It was just our bed, a dresser and a sink for $1,200 a month. [Laughs] That’s what we had to do. It was bad.

MacDiarmid: There was no bathroom!

Ramirez: That night we were talking a lot about that history of comics and how now there isn’t space for weirdos or for anything outside the norm or what makes people money. It’s either you do tech art or fine art that makes a million dollars. Our coming together was a reaction to that.

Castelo: It’s a grim reminder - I mean, a lot of us that are still in the city love the city because of the idea of it and the history of it. Now when you walk around you’re constantly reminded of what’s missing. Part of our thing with Freak was that there was a void. A lot of the artists that were there from the early 2000s to 2010s had moved down to LA for animation or whatever. But there isn’t even too much going on now even. There’s a guy we know named Harry Nordlinger doing the Vacuum Decay horror anthology. Then there’s us. That’s it.

That area in the '60s and '70s was the hotbed of comics.

Castelo: Now it seems like everything is coming out of the Midwest.

The Freak #1 anthology was in 2018. Was that your first project you all worked together on?

MacDiarmid: Yes.

Castelo: Yeah.

MacDiarmid: It was pretty bad, that first book, but it was definitely fun. We were always printing our anthologies for free—if we could and we were sly enough—or for very cheap at SFAI. That was the first one, but we’ve grown a lot since then.

Was it just you three in the first volume?

MacDiarmid: Some friends too.

How were those people selected?

Castelo: I think in the early stages, it was all people we knew or interacted with and we wanted to showcase their work, which is what has always led us. But in those early ones it was more limited to people we had spoken to. We would have had to build up courage otherwise. [Laughter]

Ramirez: I think the first issue was a lot of people we knew at SFAI. I remember really attempting to indoctrinate people into making comics. [Laughter] There are so many people who are beautiful artists and sometimes make sequential things automatically. I feel like if some people are given a space, they respond to it in a really exciting way.

You used the term “indoctrinate” - was it a tough sell for some people?

Ramirez: No! People were excited to make something. When you make an experimental space where the perimeters for people to bounce off of are pretty vast, people respond. That’s really exciting to me.

MacDiarmid: When we started it, it was less of, “Oh, I love these comic artists and I want to show people their comics,” and more like, “We don’t know many people yet and we just know fine artists.” We were at an institution where there was a teacher who once said, “There will never be an illustration department!” It felt like she was taking a stand against us. What the fuck do you have against fun, dude? [Laughter] She was a painting teacher. In those early issues, a lot of the incentive was talking to people and telling them, “You don’t do comics? You can try it! Everything can be a comic! We’ll literally print it out for you and sell it.” Like what Mara said, we were trying to indoctrinate people.

Mara, you talked about creating an experimental space. I’ve been thinking about that term “experimental” a lot recently and how it’s used to describe art, especially certain comics. Do all three of you consider your comics experimental at all?

Ramirez: I do. Mine are.

Castelo: I don’t.

MacDiarmid: No.

Castelo: I’m trying to recreate the wheel, but just as round as possible.

A lot of reviews and discussions around comics like the ones Freak makes and publishes uses words like “experimental”, but I’m not sure what that word even means anymore. Just outside the mainstream or zeitgeisty art style of the moment? I have read a majority of all your work, or at least what I could get my hands on, and I don’t personally find your work “experimental”. I find all of your work very natural to follow, but you’re all just aiming at different targets. Does that make sense?

Ramirez: I think you can be experimental and still be accessible, which has been a really big thing for me to learn. I do come from a painting background and a lot of my stuff was making sequential things automatically, but I think if you saw the things that I hide… [Laughter] Those things are really difficult to follow. I remember thinking, “It doesn’t matter. If somebody cares, they’ll do the work.” But in reality, I don’t want to be inaccessible. I want to express feelings and concepts that people understand and connect with.

Castelo: With the anthologies, the way we’d been doing it for a while is we’d all curate it at the same time. We all picked two artists, so then you’d get everything. Mara’s artists would be a little bit more poetic and quiet. Mine would be more illustrative and cartoony. I think Miles is sort of in that same boat that I’m in.

That’s interesting. I didn’t know you regimented the anthologies that way. Have you done that for every issue?

Castelo: Every issue except the #9/10 double issue. At #9, we lost our printing capabilities because our school shut down. So Miles had been sitting on his issue for a while because we had nowhere to print it. Then I organized something with Tiny Splendor, the Risograph press. What I was trying to say was, at that time, we were going to start doing our own issues. We did that for #9/10, but now we’re going back to all curating at the same time.

Ramirez: We did a few issues where each person edited the whole issue.

Castelo: Oh yeah, we did. We totally did.

MacDiarmid: This is the first one where we all collaborated on throughout the whole thing. Before, we’d take turns.

Are you talking about an upcoming issue of Freak?

MacDiarmid: Yeah, the next one. We all worked together and picked people. Now we have to find a printer.

Is this a big scoop? Freak #11 is coming?

Castelo: Yeah, and put out a “Help Wanted” sign for a printer. [Laughter]

MacDiarmid: Make that the headline!

Castelo: I’ve talked to a couple people, but we just had such a sweet deal with Tiny Splendor where they just paid for it and then split the edition in half so they could make back their money. The pandemic has made it really hard to find a press that will do it for free. [Laughs] Once we’re all a little bit more free, we’ll figure something out and get it printed. But it’s all ready to go.

That's good news. You’ve done 10 issues of the Freak anthology in less than five years. Do you find this pace sustainable?

Ramirez: We were doing bi-monthly for a minute and I think that’s why we have so many issues.

MacDiarmid: That’s when we had SFAI and we could jaunt out of there with a bunch of paper under our arms to go fold it. But I think the quality is more controlled now. I put some garbage comics in those early issues. [Casey laughs]

Castelo: I don’t stand by everything we’ve done.

A few early issues have written reviews and comics criticism in them. Speaking of indoctrination, I hope that’s something you all want to keep exploring.

Castelo: Yeah, I’d like to do that for the next one too. I think in trying to make a good anthology you need that. Why do you make an anthology? To make your voice heard, and that’s one of the more literal ways to have that happen. We want an anthology that is more than just comics.

MacDiarmid: I always tell people looking at an anthology that it’s really the best bang for your buck. If you really do hate a comic in there—there’s such a weird, wide breadth of different styles and artists—you might love the next story. We want to make a big bag of candy. Sometimes you might not like the nasty, slimy licorice in there, but there’s probably something good that you’ll like.

Ramirez: Not in ours!

Castelo: Yeah, not in ours!

Ramirez: Not in our anthologies! [Laughter]

MacDiarmid: It depends on taste, I mean.

I have some individual questions for each of you. Cristian, can I start with you?

Castelo: Yeah.

In a previous interview, you once stated, “Zines free us from the shackles of dependency.”

Ramirez: Sounds like something you’d write on Twitter. [Laughs]

It’s from an old interview. Can you elaborate on that statement?

Castelo: I think in starting Freak, the big idea was putting our own comics out. We didn’t have anyone to publish or print them. It’s sort of a trip when I talk to people who went to other art schools and learn that they were taught to make work for somebody or narrow down who they want to get published by and make their work in that mold. I think those people get caught up in having to depend on people to do that for you. Coming from the school that we went to, it was very cliquey and there was a lot of ass-kissing you had to do. Zine-making and Freak was our way to navigate out of that dependency and make work at the tempo we wanted to make work. It was solely through ourselves. [Puts on a facetious voice] It’s that DIY culture, baby. It’s my punk aesthetic. [Casey laughs] But that’s what I mean. I didn’t want to depend on anyone else, which is big coming from the guy without a driver's license. [Laughter] I’m a big depender.

Ramirez: We all are. We depend on each other.

Castelo: “Free from the shackles of dependency!”

How long have you been working on your series Wild?

Castelo: I think I started it in 2017. It’s the same two story arcs I’ve worked on now for all these years.

Do you have an ending in sight?

Castelo: No, I’m still working on the beginning! It is going to be put out by a publisher, so it will be starting up again with them, but depending on how sales are, it may be ending. [Laughter]

That’s exciting. How did that come about?

Castelo: They asked if I wanted to pitch anything and I was like, “Well, I only have this one thing.” [Laughs]

In terms of Wild and the stories you tell in that series, what makes you drawn to coming-of-age stories?

Castelo: I’m really fond of Taiyō Matsumoto’s work. I also worked with children as a camp counselor for many years. The potential that children have to become whatever they can be is really inspiring to me. That’s ultimately it, you know? There’s a dormant energy in them and it’s exciting to see what comes out. It can also be inspiring to adults who feel like their potential has already been realized. It’s a nice reminder that we’re not done growing and we can always keep going.

End the interview!

Castelo: Mic drop! [Laughter]

Mara, I wanted to start with a more technical question. Do you go straight pencil on paper?

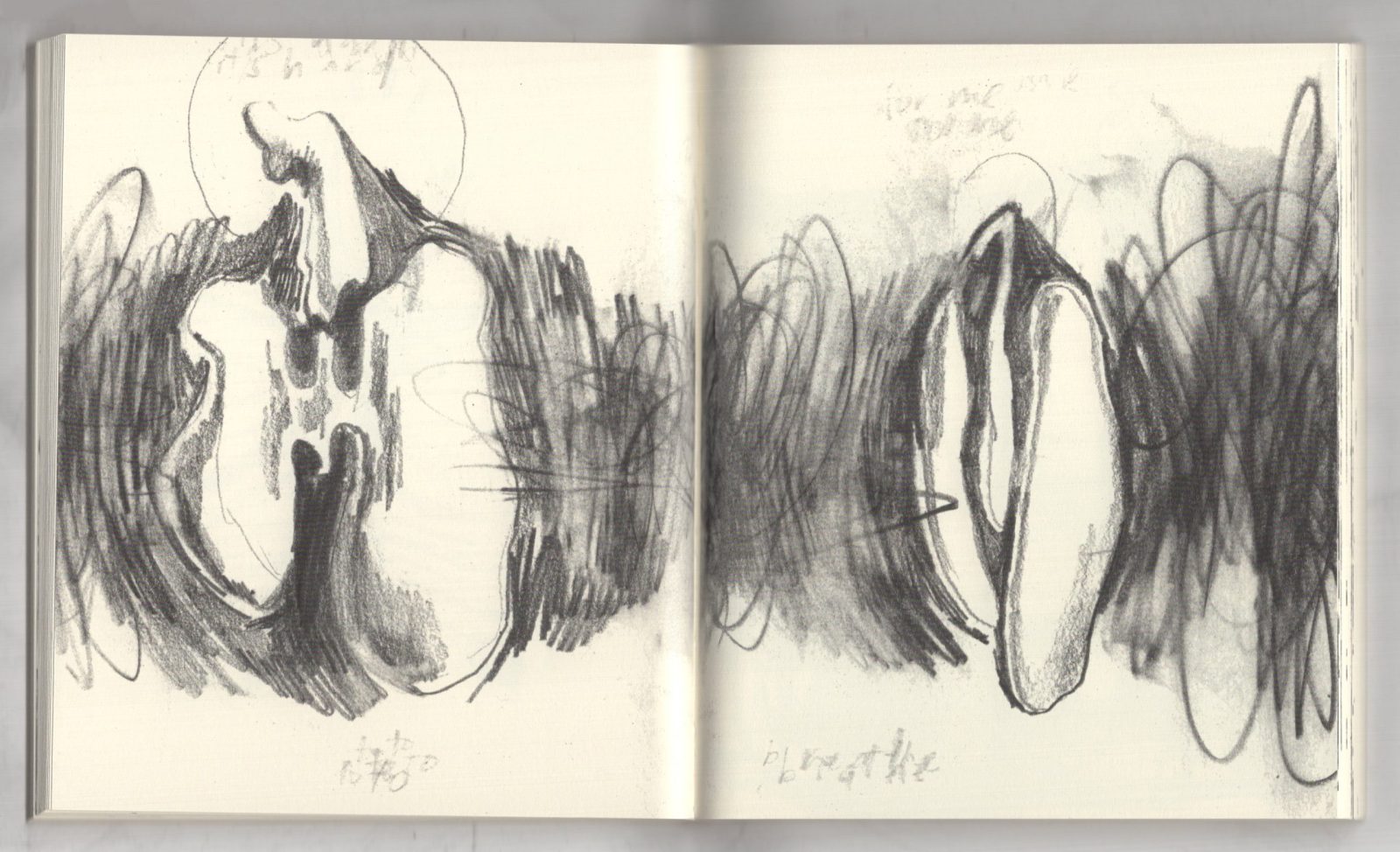

Ramirez: Yeah. It’s different for every comic that I make and I’ve been working in lots of different ways for an upcoming book that’s unreleased. But generally, I do. For MOAB, there’s a photo that Miles has of me with a big piece of butcher paper. It was a list of all the different scenes with some key words in the scenes. I have images in my brain that I think of, then I draw them.

That’s how you organized that book? With a large scroll of paper?

Ramirez: I drew all the images of the rock formations in my sketchbook on location. I came home and processed the experience of ending a relationship on that trip. I then wrote down the beats.

So you used your sketchbook pages from the actual trip you were on, then later went back and added the text in the story about the trip?

Ramirez: Yeah.

As I was rereading everyone’s work here, I noticed that Cristian and Miles solely utilize urban settings. All the work takes place in cities, and there’s a focus on streets and buildings and restaurants. But your work, Mara, exclusively focuses on open space and the land itself.

Ramirez: I don’t see a huge distinction between humankind and nature. That’s why I’m ok with living in urban areas. If I didn’t find that connection, I think I’d lose my mind. As a person, I’m really tethered to dirt. If I’m touching dirt, I’m a happier person. I drive a car—which is stupid in an urban area—but it allows me to go out and not hear lawnmowers when I want to hike. But I’m a happier person when I’m on the ground, and I notice more. I’m really interested in the intersection of what people think is “nature”—quote/unquote—and mankind or whatever. We’re the same thing, but a different iteration that’s been domesticated and screwed-up in the head.

Would you say getting outside and away from the noise is essential to your artmaking?

Ramirez: Yeah, definitely. I’m working on a book right now called Bound which is about what we're talking about. Everything is interconnected. My process for this book has been going to the ocean. We were all living together until very recently, in Daly City. Now I’m just on the other side of the Bay, but there’s this place right next to the house called “The Dumps” or Mussel Rock Park. It used to be a dump, but now it’s a beach. It’s this cliffside that’s been dug out and it’s where people used to throw trash. There’s like rugs in the sand that you can find. It’s super weird. I would hike there all the time to clear my head, but I like that connection of the human stuff at that place that’s so vast and so natural. The ocean is right there and it’s never-ending and covers most of our Earth. And then there’s this beach that’s been dug out of the earth and put on top of garbage.

Where are you in your progress of Bound?

Ramirez: I don’t know. I’m working similarly to how I did MOAB. I’m drawing straight on paper, but it’s an amalgamation of lots of little thoughts that I’m piecing together. I’m making short comics that won’t be separated when you read them, but they are different parts of the poem that I’m having to find connection points for. Right now I need to find all the connection points between different parts to tie it up.

Do you have a certain method to find those connection points?

Ramirez: In between living in Daly with these guys and moving into the place I live now, I actually went and lived in my car for a month and drove. I had this whole plan to do this big loop, like, “I want to see the United States of America!” But I literally stayed on the coast the entire time. I felt really connected to it and I couldn’t leave it. It made me anxious leaving the coast. While I was doing that, all the connection points started to come to me. Really, I just need to sit down and finish it. With this book, the ocean is the connection point. I think about different biomes that I’m relating to at different moments of my life. MOAB was the desert and my internal landscape was the desert at that moment. With Bound, it is the ocean.

You’ve been working on animation quite a bit recently. Is this something you want to focus on rather than comics?

Ramirez: Both. They’re both sequential art and they both hurt my arms. [Laughter] I would say that I’m in love with drawing.

Can I shift over to you, Miles? How's it feel to have this big book done?

MacDiarmid: For a month or so, I was hit with some raucous postpartum. I was sitting at my desk trying to draw something. Having something that took a year-and-a-half straight of these very long intensive work days to suddenly be done was not as exhilarating as I would have hoped for. Now that it’s done and sent out to people who ordered it, there’s a sense of completion and I can gradually, during this month, start to think about doing the next one. The postpartum has started to wane down a bit.

Hive: The Coronation was Freak’s first foray into Kickstarter. How was that experience?

MacDiarmid: It was pretty good. I enjoyed running it. It’s an intuitive site. They take a bit more money than I was expecting. The worst part of it was the constant self-promotion and battling with the social media algorithms. Telling people that the Kickstarter campaign was active was much harder than running the actual Kickstarter. I was extremely stressed out for the first week or so. There was a little voice saying, “It’s only the first week, fella,” but there was another voice going, “It’s starting to plateau!” But it made the goal about halfway through the time. It’s a full-color comic that ended up being extremely expensive to print.

It’s a hefty book. Is crowdfunding something Freak will go back to in the future?

MacDiarmid: We might very well do that.

Castelo: Yeah.

MacDiarmid: We’re talking about it, especially because we’re in a pickle. And a jam. We’re in pickle jam for the next issue of the anthology. We’re talking about it.

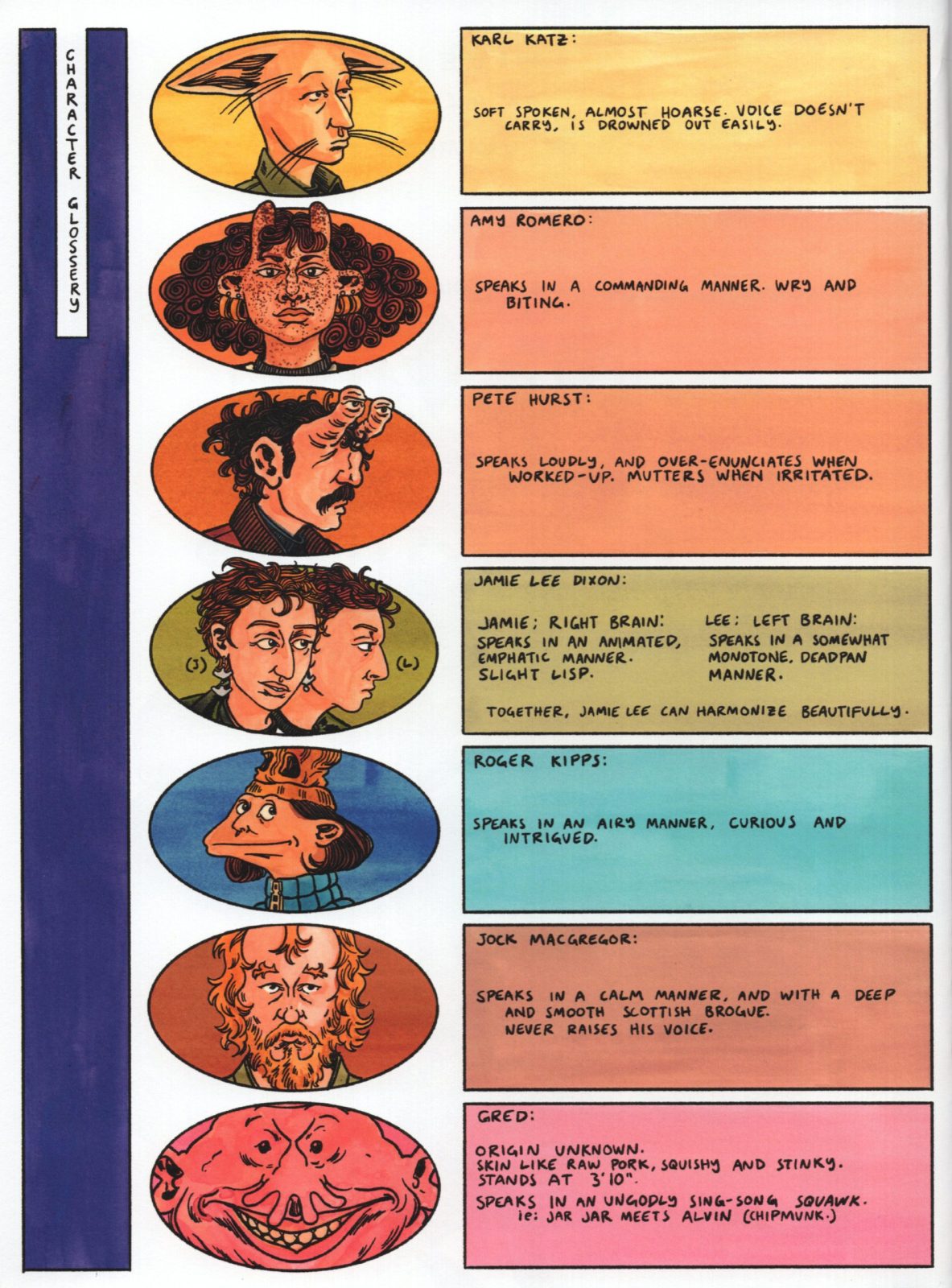

Hive has a huge cast of characters who you feel intimately familiar with. Who are these characters to you?

MacDiarmid: For the main cast—who I consider to be Pete, Karl and Amy—I try to channel myself for those characters. Pete is my excuse for being the Larry David I want to be and say the obnoxious, judgmental things that pop up in my head. He’s kind of a dick and a hypocrite. For Amy - I don’t need to get too much into it. They’re mostly me. The supporting cast is usually based on people I’ve met or know.

It was an interesting choice to create a character glossary at the beginning of the book where you exclusively describe how they all speak. I don’t think I’ve read something like that before.

MacDiarmid: I was proud of that idea.

Castelo: When I read that, I was reminded of a Simon Hanselmann reading we watched. We had this realization like, “Oh, all these characters are Australian.”

MacDiarmid: [In Australian accent] They talk like this in a sort of deadpan way.

Castelo: Yeah, I hadn’t thought of that before when reading Simon’s comics.

MacDiarmid: One of my main critiques of my earlier work is that all the characters sort of had the same voice. I was writing each character with similar speech patterns and they all had this sort of pop-y, modern way of speaking. In this book, I definitely pushed to make the personalities extremely different, or as different as I could. The voice guide helps people with that.

Are you a fan of sitcoms or media with large casts? Does that translate over into your comics?

MacDiarmid: I’m hugely inspired by Seinfeld. We artists spend a lot of time at our desks or in our beds, working for 15 hours straight, so I go through a lot of sitcoms. The stuff just sneaks into my head, the snappy back-and-forth stuff that I try to do. I think it’s subconsciously channeled from all those sitcoms I’ve put away.

The book goes from a slice-of-life comedy at the beginning to a near-apocalyptic ending. Were you concerned about having such a drastic tonal shift?

MacDiarmid: No. I was taking a lesson from myself because in my last larger comic—a 50-pager or something—I really wanted to channel pure slice-of-life. It was at the point where I took a whole scene from a Gordon Ramsay reality show and drew it frame-for-frame. I was like, “I want to be as real as possible!” But, obviously, Jaime Lee has two heads and stuff. We’re hard on ourselves as our own critics, but I thought that that comic in hindsight was somewhat boring and aimless. There wasn’t a lot of plot. I wanted to capture real conversation and then I made that. But, honestly, I just made it to make it. I learned from that and made sure there was at least some sort of through-line and plot. I always liked stories that don’t have a rising tension that reaches a climax, but rather sucker punches you. That’s what I was going for. Our friend described the book as a slacker comedy with a “what the fuck just happened” ending.

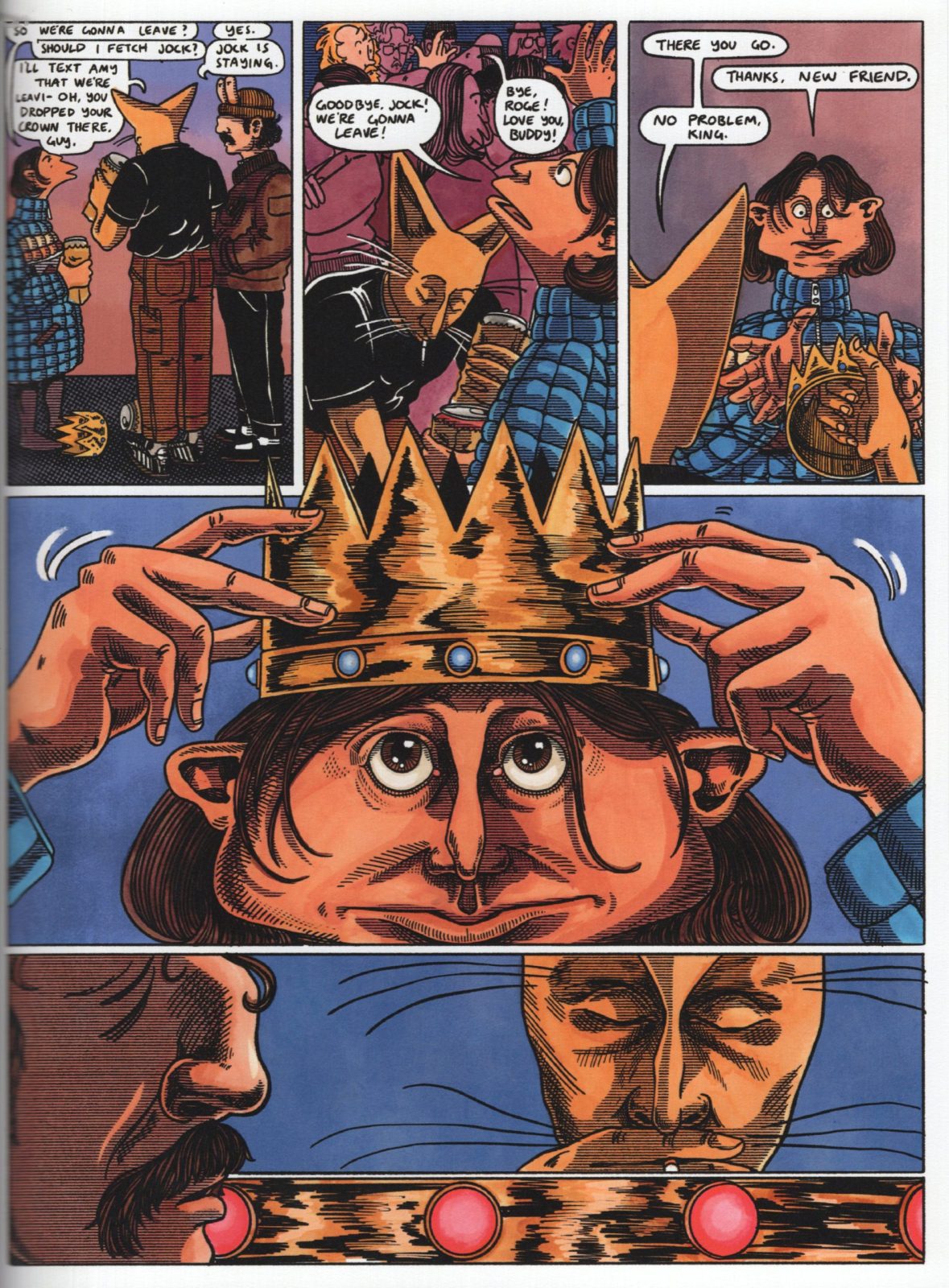

When did you decide that the crown being placed on people's heads was going to cause the downfall or have that effect in the story?

MacDiarmid: I really wanted to take a break from the rigidity of trying to capture real life. I wanted to let something absurd happen in a world where there are characters that look like that. It’s a comic and anything can happen in a comic. I had this little character named Gred, who’s a disgusting little creep.

He’s a scary guy. [Laughter]

MacDiarmid: His weiner’s out. He screams. He’s abrasive. I made that guy the crux of it all. And he wears a crown.

Gred’s crown causing people to devolve into their worst-possible selves—just base vileness—made me think about the last 6 or so years of living here in America. Is that a fair read or am I projecting politics onto your work?

MacDiarmid: I love that read. I’m open to any and all reads, especially politically. Even if you’re not intentionally political, you are political by making art and whatever you put out is a statement.

Now you’re on tour with your band Fake Fruit. You’re the drummer, correct?

MacDiarmid: I am that. Fake Fruit is driving around the country right now. Last night, we just played in Denver. Tomorrow night we’ll play in Milwaukee. It’s a lot of driving, but it’s pretty fun. Live rock music is fun to play.

Let’s talk about Freak's most recent publication - Oboy Comics. Who is Shaheen Beardsley? How did you meet this artist?

Castelo: I think we met online. He went to CCA [California College of the Arts], our rival art school. [Laughter] They won because our school went out of business. It was like a lot of our relationships, where they come from people who are pushing against the grain and we find each other online. Shaheen had been making really high-level work from the moment I met him. I think I proposed publishing him a while ago, so it’s been something we’ve wanted to do for a long time.

You proposed that he contributes to the Freak anthology or proposed this giant book?

Castelo: He was in one of the anthologies and afterwards I proposed we publish his work and just recently we did it.

Why--

MacDiarmid: “Why this book?” [Laughter] Were you going to ask, “Why did you do this?” If you read Oboy, it’s fucking vile. I love that comic.

No, no. I was going to use an NBA term and ask outside the “Big Three”—which is all of you—why did you decide this was your first book publishing someone else?

Castelo: We had an art show right before the pandemic started and Shaheen sent us the “skinning” pages. I think the only story he’d ever sent me before was one of those “I’m god and I’m writing you out of the story” type comics, you know? Then he sent these pages where someone is being skinned. [Laughter]

MacDiarmid: Then we put those pages on a wall for many people to look at!

Did you feel any added pressure because you were publishing someone else’s work?

MacDiarmid: Cristian did the brunt of the work.

Ramirez: He’s the midwife of Oboy. This is Cristian’s baby he helped bring into the world.

Castelo: We do put out a lot of people’s work through Freak with our anthologies. With something like this, the only difference was that we had to communicate with each other more because it just costs so much fucking money. We want to put more people’s work out and it’s something we’ll do in the future. Shaheen’s book was just one of the first things where we all said, “We can do this for people. Let’s do it for this person.” I'm just a big fan of Shaheen and he deserves to be out there.

I have one more question for everyone. On your website you have a statement that reads: “We challenge and oppose gatekeeping, inaccessibility, and pretension. Comics for the people! Comics for fun and comics for love and comics to be funny!” Who wrote that? Can you break that down for me?

MacDiarmid: We all wrote that. We yelled words at each other. At the very end, someone went, “And comics to be funny!” We live in the Bay Area and there are a lot of fakeys out here.

Ramirez: Don’t put that in the interview! [Laughter]

Castelo: There’s a lot of poseurs out here.

MacDiarmid: A lot of shallow people will judge you on first glance, but not us. No, sir.

Castelo: I do think it comes from that moment of getting out of college and wanting to be a part of anthologies, but all the anthologies are curated so that the most popular artists are being picked. There’s this feeling that you want to break into a scene but it’s so difficult. You want your work seen, but you get “cool guy’d” at comic shows and fairs. It makes you feel shitty. We just wanted to combat that by being as positive and inclusive as we can. That’s my biggest thing personally about Freak - I want to create a space where people feel welcomed. I think some people want to make their names known through negativity and infighting and shit like that. But we’re all peace and love here in San Francisco. We’re Freak!