This interview—or an earlier version of it—has been gestating for over a year. In September 2020, after Diamond Distributors mispriced a six-issue package of Craig Thompson’s comic book Ginseng Roots (Uncivilized Books), I contacted artist and Uncivilized publisher Tom Kaczynski and scheduled a short interview about Diamond’s mistake. Tom and I got to know each other during that chat, even as Diamond’s flub proved inconsequential and our interview irrelevant.

In late summer 2021, Tom suggested that we do a new interview, about both his personal projects and the upcoming Uncivilized publication slate. The freewheeling tone of our dialogue reflects both our rapport from the earlier interview and intellectual affinities we share. We shift from discussing Fantagraphics’ forthcoming tenth anniversary edition of Tom’s Beta-Testing the Apocalypse to Tom and Gabrielle Bell’s Uncivilized Territories podcast to J.G. Ballard to the recent Our Stories Carried Us Here collection of immigrant stories to the design of Matt Madden’s Ex Libris with ease, thanks to Tom’s relentless curiosity and willingness to challenge aesthetic orthodoxies. It was a joy to talk to Tom twice.

Craig Fischer: There’ll be three new stories in Beta-Testing the Ongoing Apocalypse. Where did they originally appear?

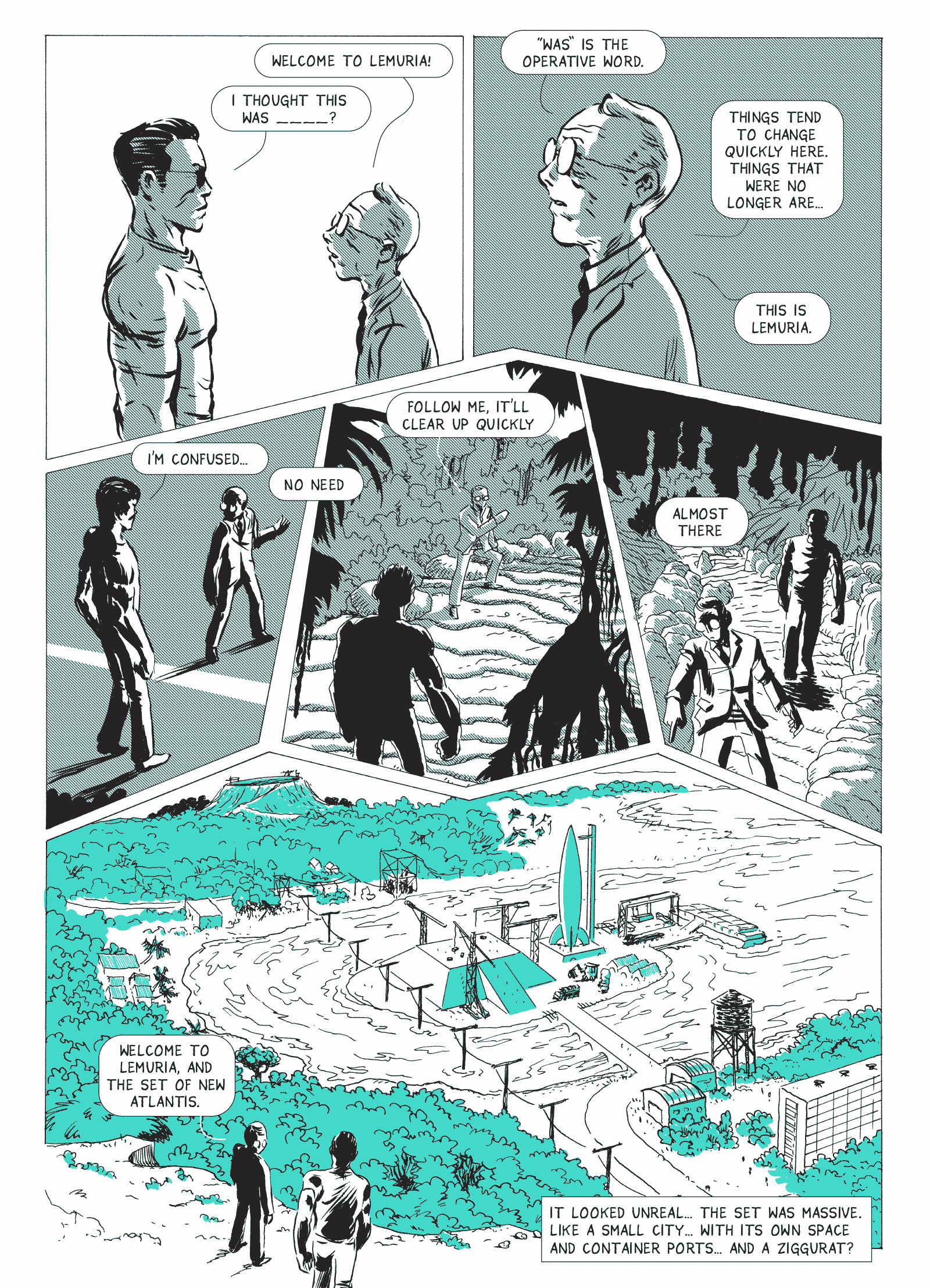

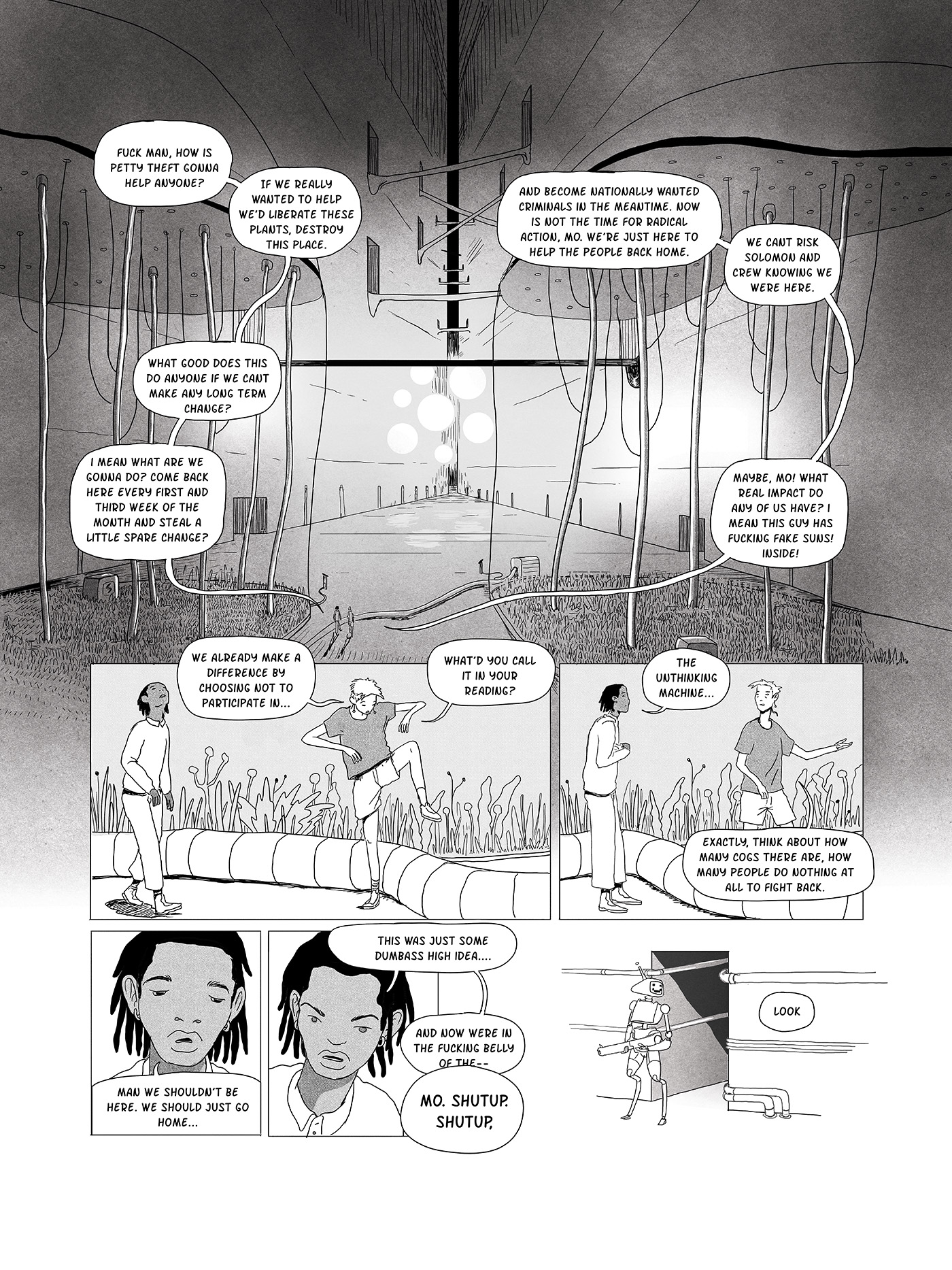

Tom Kaczynski: There’s a new introduction by science fiction author Christopher Brown and three new stories in the collection, one of which was never published before. One of the additions to Ongoing Apocalypse originally ran in Twin Cities Noir, an anthology published by Akashic Books; mostly, their noir books are prose fiction, but I got to do a comic. The other previously published story is “The 36th Chamber of Commerce,” which ran in World War 3 Illustrated. “Commerce” also got recently translated into Portuguese and ran in Portugal’s oldest anarchist newspaper! The brand-new story is about an Elon Musk-like character named Nelo Task. Ongoing also includes several pages of notes that explain the stories written by Adalbert Arcane.

Was it unsettling to revisit work you did a decade ago? I ask because you and Gabrielle Bell do a podcast, Uncivilized Territories, and one of your episodes focuses on the lures and dangers of nostalgia. You and Gabrielle talk about the need to separate the art or artifact itself from personal feelings of nostalgia: for Bell, it’s separating a Garbage Pail Kid card from the nostalgia she feels for the time in her life when she loved the Garbage Pail Kids. Did you experience nostalgia when you began to revise Beta-Testing?

Not really. To me, it still feels fresh in some ways. It was late when it came out, and there wasn’t much hoopla around the book, so it feels like a lost artifact to me and maybe other people as well. Reading the new introduction by Christopher Brown gave me a fresh look at Beta-Testing, as did revisiting the stories through the eyes of Adalbert Arcane’s notes. They helped me tease out some of the themes I was thinking about back then and had forgotten entirely. I thought it was a valuable exercise for myself as an artist and writer. It never felt nostalgic in any way. It felt more like a continuation.

The three new stories also put a nice capstone on the stories previously in Beta-Testing. With the new comic I just finished, it was fun to get into that mindset again, but differently. I’ve wanted to create some kind of utopian work that envisions a more positive future for the world, even though I keep falling back into dystopian themes. That’s easy to do, especially these days. [Laughs.] But the new story—which is called “The Utopian Dividend”—tries to find something positive to say, even though most people will read it as very dystopian. But there’s a utopian core to it.

Why is creating a utopia so important to you right now?

Before I emigrated from Communist Poland, America looked like a utopia. The United States was (unintentionally, through television shows) portrayed in a positive light in Polish media—though when you come here, you realize that America is mostly just another country. It’s not some kind of a “city on a hill.” But still: there’s still something here that’s difficult to replicate elsewhere. There’s something underneath all the negativity; there’s still something utopian about the American project.

Is part of that utopianism the ability that people have to remake themselves in America in ways they can’t in other countries?

That’s part of it. If you stay where you grew up for most of your life, you’ll always be rooted there. If you’re from one country, and then you go to another, you have the opportunity to remake yourself and create something new. If I had remained in Poland, I don’t know if I could’ve done comics the same way I’m doing them now. The comics industry nearly disappeared in Poland for twenty years after the fall of Communism.

Poland has exciting comics again, but that was not the case when I began making comics as a kid.

You grew up reading American superhero comics, right?

At first, I read Polish comics. There were a lot of Polish comics available in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but after 1989 that whole industry collapsed for several years. For the most part, it became impossible to do comics in Poland. Then when I moved to Germany—before I moved to America—I discovered American superhero comics.

I read one weird artifact when I was a kid in a Polish / English library. It was a comic starring the Fantastic Four and Spider-Man, so maybe it was a reprint of some Jack Kirby annual. I don’t know. I just have this vague memory of it…

It’s nostalgia! Don’t look back! [Laughter.]

I think nostalgia is a danger, but you can recover something interesting if you approach it with a clear head. On the podcast, I talked about Chris Ware and Seth using their nostalgia to create something new. Their projects aren’t entirely nostalgic; they synthesize something old with something new. Human history goes back thousands of years, and so many paths not taken, I think it’s occasionally worth exploring those paths, as long as you don’t just wallow in nostalgia.

Let me ask a few more questions about the revised Beta-Testing. In re-reading the original version of the book, I noticed that your drawing style owed a lot to Dan Clowes. Is that a fair assessment?

For sure Dan Clowes is a significant influence on me. I was reading all the independent comics of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

Also, I think that your philosophical concerns have changed since the first Beta-Testing. There are strong influences on the original book—in your critique of car culture, and in your interest in psychography, I see both Jean-Luc Godard and J.G. Ballard. Now, in 2021, you seem less influenced by those artists and much more interested in aesthetics. “Adelbert Arcane” talks instead about how comics might work in new formalist ways. Your concerns have changed in ten years—which is good, because you want to mature and try on different ideas and art-making approaches. [Laughter.] But was it strange to return to those ideas and preoccupations when revising the book?

That’s a big question! [Laughter.] I see continuity between those ideas and what I’m thinking about now. For me, Ballard’s fiction, however critical it may be of certain aspects of culture—cars, suburbia, whatever—always involves excavating a primitive core underneath the civilized façade. And I’m not sure that’s the right way to read Godard: he’s very political, but in Weekend, there’s a constant push-and-pull between Modernity, embodied in traffic jams and automobile accidents, and the results of Modernity, people surviving the crashes to move back into the wilderness. That’s Ballardian too. It’s the primordial humanity that re-emerges once you strip away the trappings of civilization.

My new stuff involves thinking about comics as a medium for philosophy. I don’t know if I’ve created comics that have achieved that goal, but I’m working towards that. Comics-making overlaps with the mental baggage we have as humans—both explore how we interact with the world, conceptualize ideas, orient ourselves in space, and think about space as a metaphor and a trigger for our memories.

The ancient Greek technique of the “memory palace” is something we are; we as humans are memory palaces, whether we use the method consciously to memorize Homer or subconsciously aggregate ourselves into a person through our memories. And comics approximate a memory palace on the page: the panels and pages operate in space and time coordinates, and images can anchor more abstract, more ephemeral words.

In terms of using comics for philosophy, philosophers use visual metaphors in their language, and comics can make those metaphors more explicit and concrete. I wonder if there’s a way to push comics in that direction; not all comics, but some. There’s a place for superhero comics, there’s a place for YA fantasy, but I’m trying to make room for philosophy in the medium, though I’m not sure where I’ll end up with all this…

Are there precursors who have tried, intuitively or consciously, to push comics into more of a philosophical direction? Or tried to achieve a blend between comics and philosophy?

Scott McCloud is maybe the most explicit example here…

Kevin Huizenga?

Kevin, absolutely. I think Cerebus was doing that on some level. [Laughter.] I’m re-reading Cerebus right now, but I don’t have a handle on it yet—it’s a mish-mash in my head right now. Alan Moore, too, and much of it within the constraints of the superhero genre. Chris Ware, Dan Clowes…although Clowes has a self-hating relationship to philosophy. [Laughs.] When he philosophizes, he undermines it at the same time.

When Clowes did those multiple-story issues of Eightball, he always juxtaposed philosophizing or ambitious artistic intent with strips like “Shamrock Squid,” [Laughs], which deflates what Clowes saw as his own pomposity.

Exactly. And that was the fun of Eightball, right? His Modern Cartoonist pamphlet uses such heightened language while showing you a picture of a cartoonist slitting his wrist. [Laughter.] You know Clowes believes what he’s writing one hundred percent, but he’s afraid to sound too didactic or committed.

It’s interesting that you mentioned Alan Moore, because your discussions of language with Gabrielle on the Uncivilized Territories podcast struck me as similar to some of Moore’s theories in his comics, superhero and otherwise. Both Alan Moore—and Grant Morrison—believe that language is a code that underwrites, and almost determines, the ways we act and think.

Both of those writers use magic as a metaphor for being a writer. Or they just literally claim to be magicians. [Laughter.] I’ve been influenced by their thinking about this stuff. Moore’s idea of Immateria—the Archipelago of Platonic ideas—is a memory palace itself, a city of archetypes. I’m very interested in those ideas, and in my comics—maybe not the ones in Beta-Testing specifically, but in Trans Terra and Trans-Alaska—I play with the notion of ideas being places that you can visit and explore. I owe an enormous debt to both Moore and Morrison; I read them a lot in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and I revisit their work now and then.

And this is a breakdown in those genre distinctions you were making. You said “There’s a place for superhero comics,” yet you derive some ideas and inspiration from superhero comics, as well as all the other voluminous reading you do that you discuss in the podcast! [Laughter.] The book behind the theory of language we’ve been talking about is…

… S.S.O.T.B.M.E. by Ramsey Dukes. Moore and Morrison were fortunate to be writing when they did: superhero comics were in flux, the whole world of comics was unstable, a point I’ve brought up in the column I write for The Comics Journal. There was an openness, an opportunity to throw new ideas into the superhero milieu. That’s not happening anymore.

As you said on the podcast, the superhero comics these days are afterthoughts to the appearances of superheroes in other media.

They’re the merchandise for the movies. At least Zack Snyder’s film version of Watchmen (2009) was faithful to the comic. Many Marvel movies take ideas from older comics but without similar reverence. The new comics feel like they’re regurgitating what the movies do.

I’ve given up on the “Marvel Cinematic Universe,” which was only driven in the first place by my dangerously nostalgic attachment to those characters and stories. But it seems like “Phase 4” of the MCU is going to be a rewrite of Alan Moore’s Supreme.

I don’t have Disney+, so I haven’t watched any of those shows.

That’s fine. Don’t rush. [Laughter.]

No comment. I don’t know what’s going on anymore! I haven’t thought too much about the Marvel movies that I’ve seen, but I’ve watched them because it’s fun and because I wondered, “What are they going to do with Thanos?” Thanos was an important character when I was a kid.

We’ve been talking around Uncivilized Territories: you and Gabrielle started the podcast in March. Why did you decide to start a podcast?

People during 2020 were starving for companionship, for hanging out and chatting with friends. Both Gabrielle and I were listening to several comics podcasts. But, I felt like they fall into two categories: they either talk nostalgically about older comics (Cartoon Kayfabe does a great job with that), or they feature some interviews with contemporary cartoonists with new books coming out. There was very little idea-talking. Maybe Gabrielle and I have talked too much about ideas and not enough about comics.

But you two did a whole episode on your favorite comics cons and festivals, so… [Laughter.]

We felt like we needed to say something about comics! We hope to infect the comics world with ideas that come from outside comics. There just aren’t many venues where people talk about ideas. Most reviews don’t go there, and there’s no media ecosphere of comics and ideas. Maybe some theorizing is going on in academia, and the old Comics Journal was talking about ideas when they published weird postmodernist writers like Kenneth Smith. [Laughs.] Whatever you thought of that writing, it elevated the discussion of comics to address big ideas. And Uncivilized Territories is another opportunity to do that.

The conversations with Gabrielle will continue every month, but I’ll also be doing interviews with other writers and artists.

Can you give us a preview of who you’ll be inviting to the show?

We’ll be talking to Craig Thompson. I want to speak to him about Christianity and other religions and how religion informs his comics. I also plan to talk to Matt Madden, whose book Ex Libris will be published by Uncivilized in the fall. Our discussion will probably go deep into formal comics experimentation and metafiction in general. We’ll want to talk about Italo Calvino and other metaphysical writers and what’s interesting in that prose work to cartoonists.

There’re a few others I want to interview, including Greg Hunter, who wrote a book about Dash Shaw for Uncivilized’s “Critical Cartoons” series. Greg and I will do a deep-dive episode like the one Gabrielle and I did about Olivier Schrauwen’s comics—so first, we’ll talk about Dash without Dash being present. [Laughs.] And then later, Dash could join the discussion and respond to what we said about his work and add to the conversation.

It’s interesting that you bring up the notion of comics discourse that focuses more on ideas, rather than issues of craft or personal interviews with creators. It’s what you’re trying to do with Uncivilized’s “Critical Cartoons” series (the books on Barks, Brown, Doucet, and now Dash Shaw): transmitting ideas about comics in ways that aren’t too academic but still rigorous. Is that the purpose of both the “Critical Cartoons” books and the podcast?

Absolutely. I don’t want to get too academic with these projects. Academia has its place, but academics often speak only to other academics, and those conversations are difficult to translate into the larger public discourse. Valuable work, but it’s hard to get the public excited about it.

I think we undervalue big ideas as something the public might be interested in; I’m interested in popularizing science. Every discipline should have someone like Neil DeGrasse Tyson, who popularizes complex concepts for the general public. And usually, the public is excited to learn that there are weird, new theories about dark matter or string theory…

Comics can do the same. There are ways to talk about comics that are not too esoteric and tell people about the potential of comics to express ideas. But all this is in an embryonic state.

But is it? Greg Hunter, the writer of the upcoming Dash Shaw book, has written for The Comics Journal, and so have you. Do you think the Journal charts that middle ground between knee-jerk celebrations of comics and the theoretical rigor of academics?

They’re still the best publication for that. However…

There’s no Kenneth Smith around these days… [Laughter.]

It’s less even about that. The difficulty for The Comics Journal, at least over the last few years, has been less about the quality of the writing and more about the design of the TCJ website itself. Before the recent remodel, it was difficult for editors to foreground content and readers to read it on their phones. In the past, you could get the old physical Journal at any comic shop, and it enraged you, or you liked it. [Laughs] The old TCJ site was not very accessible.

I’ve written some really long pieces for the online Journal, and one complaint I hear from people is, “Oh, I saw your essay, but it ran longer than a thousand words, so I didn’t read it.” Do you think there’s something implicit on the Internet that prevents people from devoting full attention to online writing?

People still want to read quality long essays, but the process needs to be easier for them. The Internet favors short pieces, but a sub-audience seeks to read online and in depth, and the medium should facilitate them. And if you can build a site that leverages in-depth writing well, you’ll cultivate an audience. People still read long articles on politics in The New Yorker, but The New Yorker has an up-to-date design that makes the text easy to read. Maybe the Substack model could work, where you get a complete essay in your e-mail. The Comics Journal needs to catch up to these new models.

Even the print Journal has always been aspirational, since they’re always struggling with limited resources.

Of course! I don’t deny that there are limited resources.

You’re a publisher! You know about limited resources! [Laughter.]

But the best reviews of comics are still mainly in the Journal. You rarely see something as good as just a mediocre Journal review anywhere else.

For me, the Journal’s only competitor is SOLRAD.

Though SOLRAD is even smaller—yes, they’re the only other game in town. Occasionally, you’ll read a great review in The New York Review of Books or the L.A. Review of Books. But they typically review only the high-profile projects that everybody’s reviewing anyway.

There’s not much of an ecosystem for serious discussion about comics. The Uncivilized Territories podcast is my small contribution to the cause…besides the books I publish! [Laughs.]

To a vibrant, idea-driven comics discourse!

Yeah, yeah. [Laughs.]

I want to go back to your idea about this middle space between mass cult and academia. Do you try to teach from that in-between spot? In spring 2021, you taught at the University of Minnesota, is that right?

Yeah, and I also teach at MCAD [Minnesota College of Art and Design] in the fall. Those classes are hands-on; the UM course is part of the Printmaking department, so the focus is on making zines and comics. Theory and ideas are only a tiny part of that class. My MCAD class is mostly about publishing, about the nuts and bolts of the current comics market. I update that every year based on whatever events have happened in the distribution and sales of comics.

We’ll get to the Diamond upheaval in a little while. [Laughter.] So your classes aren’t designed to translate theoretical ideas into practice?

Not so much. In the past, I have taught a class in experimental comics, where I’ll bring in some of those ideas—it feels appropriate then. But my Publishing class is almost all practical advice. I talk about the fragile ecosystem for comics reviews and encourage students who are also writers to contribute essays and critiques as a secondary practice to their art. It’s an essential contribution to the medium.

If they write their reviews as a way of promoting themselves and the artists they like…

I don’t see any problem with that.

People can refuse to listen to your interview with Craig Thompson if they consider it a conflict of interest.

I don’t see artists promoting other artists as a problem. The history of literature is members of literary circles promoting each other. Without that promotion, what is literature? Not much else.

The artists themselves go a long way towards establishing a canon, and then they fight to place themselves in it. [Pause] Did you find it difficult to teach practical comics-making classes on Zoom during the quarantine?

It was relatively easy to transition online. The UM class was more of a chore because it’s more hands-on. It was also hard to figure out what resources were available to individual students: “Here’s a student who can screen-print, and here’s someone who can barely access a printer.” That was challenging. It was easier for the MCAD class, which mainly involved talking about the industry and showing them how to create print-ready files. The guests for the MCAD class would’ve probably spoken to the class over Zoom anyway…

Who did you invite to class?

One of the most popular guests was Spike Trotman from Iron Circus Comics. All the students liked her. She’s very knowledgeable about crowdfunding and digital comics, with which I’m not as familiar. It’s important to hear about those topics.

I like bringing in a mix of people who’ve been around the block a little bit and people who have just started in the industry to show different challenges. You have different obstacles to overcome when starting your career than when you’re an established artist or publisher.

It’s fun to bring creative people to class. I try to do it every semester, depending on whatever funds I have available from my department. My comics class in the spring ended with a terrific conversation with Eleanor Davis. She was frank about the problems she faced when she first started her career. When one of my students asked her about work-for-hire, she said, “Aw, don’t fuckin’ do it.” [Laughter.]

Everybody’s done some work-for-hire…

You have to earn the authority to say that it “fuckin’ sucks.” [Laughter.] One of your current projects was serving as co-editor of a comics anthology about immigrants in the United States, a book called Our Stories Carried Us Here. How did you get involved in that project, and how did your own experiences as a Polish immigrant influence what you brought to the book?

Green Card Voices is an organization located here in Minnesota that collects immigrant stories. Voices is run by Tea Rozman, from Slovenia: she’s the Executive Director of Voices and one of the editors of the Our Stories volume. We both come from Slavic-speaking parts of Europe, so we bonded over that. Green Card Voices happened to share the same office building with Uncivilized, so we got to know each other. Voices also joined the book distributor Consortium, so our paths kept crossing more and more.

At some point, Voices became interested in turning some of their immigrant stories into comics, and I encouraged them to do it. I didn’t know if they would pull the trigger on the project [Laughs], but they did, even in a challenging pandemic year, a year filled with Zooms. We had very complex Zoom conversations among all the different contributors, among the writers working with the artists to translate their stories into comics.

Occasionally, we’d have multiple go-betweens. Some of the artists are in Africa—one of them is from Ghana—and some didn’t speak English, so we had someone on Zoom that could translate what the artists said into English and retranslate replies. We had another storyteller who was deaf, so we needed someone who knew sign language. But the storyteller originally learned French sign language, which is different from American Sign Language…all on Zoom! But I think the anthology came out great.

Do you have a contribution in the book?

I drew a story for writer Alex Tsipenyuk, who is from Kazakhstan. We’re both from Eastern Europe. His story was an opportunity for me to examine the Green Card lottery system in America; that’s how Alex got to America. I knew about the lottery, but I didn’t understand its mechanics, so it was interesting to describe that system in comics form and tell Alex’s story in that context.

Now let’s talk about what’s coming up from Uncivilized. Finally, right? [Laughter.] You already spoke about the “Critical Cartoons” book about Dash Shaw, but what is the general thesis that Hunter takes on Shaw’s work? I should be asking Greg this, right? [Laughter.]

Now let’s talk about what’s coming up from Uncivilized. Finally, right? [Laughter.] You already spoke about the “Critical Cartoons” book about Dash Shaw, but what is the general thesis that Hunter takes on Shaw’s work? I should be asking Greg this, right? [Laughter.]

I can arrange that! [Laughter.] If you want to interview Greg, that’d be great! I’ll give you a CliffsNotes version here: Greg looks at all of Dash’s notable books, and the final chapter analyzes Cosplayers.

Does he discuss Shaw’s animated films?

There is a chapter that mentions the movies, but the emphasis is on Dash’s comics work. Greg felt like the comics deserved more critical attention. Greg starts with some of the work that precedes Bottomless Belly Button, and Button itself. Greg focuses on the relationships among the characters, how Dash uses the comics medium to show interpersonal (mis)communication, how characters get to know each other and get in each other’s heads. Greg’s book has a consistent thesis about how people interact in Dash’s comics and how each of Dash’s books explores and complicates ideas about how people interact.

Or how Shaw’s books talk about how technology influences our interactions with each other, which is a prevalent theme in Shaw’s comics…

The issue of technology is part of Greg’s analysis.

We had difficulty getting permission to reprint BodyWorld art from Pantheon because [Pantheon editor] Dan Frank passed away during the process. Pantheon’s rights department took a while. It was a very labyrinthine process. And by the time the request got back to Dan, he had died. Unfortunate news.

You have four more issues of Ginseng Roots to go, correct?

Right. And we’ve released an actual box designed by Craig that can hold all twelve issues.

And that’s the same box whose design caused a controversy when you first announced it…?

And that’s the same box whose design caused a controversy when you first announced it…?

Yeah. At that point, we had only announced that there would be a box with artwork that wasn’t even finished, just stray images from Craig’s sketchbook. But yes, that same box finally got made. It took a long time, and we had one more wrinkle at the end of production: a chipboard shortage! That made the box much more expensive to manufacture. But it’s printed and done. A portion of the boxes will go to Diamond, an amount will go to Uncivilized’s warehouse, and if we sell out of it, we’ll make more. But right now, it’s a limited edition of 1500. You can buy a box from a retailer or us.

When Ginseng Roots is over, will you also sell the box with all twelve issues inside?

That’s the idea—but we still need four more issues! [Laughs.] We can’t quite do that yet. But currently, boxes are going to individual buyers and subscribers, and we’ll have a leftover batch after that. We’ll fill those extra boxes with issues after they come out. Or, if we run out of boxes, we’ll do another print run… hopefully, chipboard prices will drop by then!

This may be a loaded question, but you told me previously that you didn’t think that Uncivilized could compete with other publishers for the collected Ginseng Roots. But if Craig markets the collection to other publishers, is there going to be a competition between the Uncivilized boxed set and the single-book Ginseng Roots from another publisher?

Our box sets are a limited item. The amount of back issues we have is limited. I don’t know what the number will be at this point; we’ll end up with something between one hundred and one thousand sets, and once they sell, they’re gone. We’re not going to keep this in print indefinitely. There’s an end to the project, and there will be a book collection at some point.

Through Uncivilized, maybe?

I doubt it. I think Craig can command a decent advance that I don’t know if I can match. [Laughs.] I would love to do the book if he trusts me to do it, and maybe he will. But I know it’s difficult to say no to a significant advance from another publisher. We’ll see what happens.

Recently, Chris Pitzer decided to close down AdHouse at the end of 2021. I saw social media postings by several artists who thanked Chris for publishing their first book. But not later books. [Laughter.] They went with AdHouse as a stepping stone to other publishers.

Chris always positioned himself that way. He would publish the first book and encourage the artist to look elsewhere for subsequent books. Chris had clear limits as a one-person operation. He was always very upfront about that.

I’ll miss him! As a publisher who does similar projects to AdHouse—I also publish a lot of first books for cartoonists beginning their careers—I understand. I also tell my artists, “If you can get a deal with someone else, that’s probably going to further your career.” I do have a limited scope as a publisher. We’ve had some successes. Recently, for example, Ginseng Roots’ 2021 Eisner nominations [for “Best Graphic Memoir” and for Craig Thompson as “Best Writer / Artist”].

Well deserved. Roots is maybe my favorite work by Craig.

I like it too, what he’s done with the story so far.

In our last interview, we talked about the “feedback loop” Craig wanted to create by serializing Ginseng Roots. As he releases each issue, he gets comments from both readers and the real-life people he presents in the comics, and responds in future issues, making the overall work stronger. And I like his willingness to shift away from autobiography and focus on, say, the Hmong Ginseng farmer in issue #8…

I love that technique. It’s a technique I’ve used myself in Trans Terra: using a personal story as a springboard to talk about larger systems. I also did it in my contribution to Our Stories Carried Us Here, using Alex’s story to explore the Green Card lottery. All these larger systems, all these stories, and it’s incredible to see the connections between personal stories and behind-scenes events and networks and bureaucracies that you never think about until they affect you or those close to you.

Speaking of networks: in our first interview, we also talked about the state of the direct market. You mentioned that some of your sales are through Diamond, but you found it somewhat hard to work with Diamond as you started to release Ginseng Roots as a semi-regular periodical. Where does Uncivilized stand now with Diamond, and where does the comics market stand in general?

Diamond’s always been a difficult topic to discuss because of their monopolistic power over many retailers. But now that’s gone. There’s a new distributor—Lunar—who’s dealing with D.C., and there’s Penguin / Random House, that’s distributing Marvel. Diamond still gets some Marvel stuff, but they’re not the primary distributor.

I think Diamond is still distributing Marvel’s book collections?

Distribution is fragmenting, and we’re not at the end of the fragmentation at this point. I don’t know where this is going, but Uncivilized is signing up with Lunar. Uncivilized, Floating World, and Silver Sprocket have joined Lunar en masse to have another outlet for our floppies.

You depend on specific stores that carry alternative comics and order heavily from Uncivilized. Some order directly from you, but some might get your comics through Diamond. And Lunar is owned by Discount Comic Book Service, one of the biggest competitors to brick-and-mortar comic shops. Is that a problem?

I don’t know! [Laughter.] It’s all developing right now! The one clear thing is that there are not enough comics stores to cover all the different markets. This is why Amazon sells a lot of comics. Technologically, we’re changing too, and it sucks.

I love comic book stores; I want to walk into a shop and find what I’m looking for, but my favorite stores in Minneapolis (Big Brain, DreamHaven) have either closed or they’ve changed. I worked at DreamHaven when I was younger, but they’re no longer ordering the full slate of comics. I probably won’t find what I’m looking for there. I’ll browse older comics and older collections, but I’m not going there for new comics.

And other stores are further away, so it’s inconvenient for me to visit them. And I’m someone who likes comic shops, and I am willing to take extra time and effort…

I’m two hours away from Heroes Aren’t Hard to Find; they order at least one copy of comic in the monthly Diamond solicitations, but I can’t drive every week to Charlotte to comics. And Chapel Hill Comics was a great store, until Andrew Neal sold the business. Within two years, Chapel Hill Comics was closed.

It sucks! I understand the motivations of a business that realizes an audience is underserved and decides to make comics available by mail order or online. And if I can find new readers and sell more copies of Uncivilized comics through Lunar, that’s a significant gain for the artists and my publishing company.

Do supportive comic shops—The Beguiling, Chicago Comics, Gutter Pop—order directly from you?

Many do. And others want to make sure they make their numbers with Ingram and Diamond, so they use those distributors instead. It’s a mix. I love working with shops, but there’s less and less of them, and when that’s the trend, something’s stepping into that vacuum. Partially it’s Amazon pushing them out of the market, and partially it’s regular bookstores carrying comics, especially trades and graphic novels.

I’m going to sound harsh. Some of these comic-shop wounds are self-inflicted. I remember when Chris Ware and Dan Clowes broke out of the comics-store zone, and their Pantheon books became available at chain bookstores in the late 1990s, early 2000s. There was a moment where some comic book stores expanded their stock to include a curated section of graphic novels, along with floppies. At the same time, other shops went in the other direction and became more pop-culture-oriented, went all-in on games, Funko tchotchkes, collectibles, stuff like that. That was a business decision, and the bookstore model was more consistent—people want to buy books, and they will probably want to purchase books 100 years from now, whereas the collectible market is very volatile. Something is hot right now and dead next week. Treating comics as literature (not just a collectible) is a better long-term strategy.

Economically, when you’re dealing with the difference between ordering books and memorabilia that’s non-returnable through the Direct Market, and ordering returnable books through Ingram…

That’s a huge difference. Mainstream and indie bookstores did a great job building a whole new audience for graphic novels. Kids buy comics now! In huge numbers! But they’re not buying them in comic book shops!

I’m saying the word again: we have a sense of nostalgia for comic book shops. I remember finding new issues of Hate or Eightball in the early 1990s at my local comic shop, or comics by Roberta Gregory…

But by the early 2000s, that was gone. Love & Rockets was maybe the only comic that held on, and maybe Cerebus, and that was about it. When I started Uncivilized, I decided not to go into the Direct Market because I didn’t think Diamond would even talk to me at that point. We got involved with Diamond to publish Craig. He helped to open that door for me. Before Ginseng Roots, we were almost exclusively bookstore-oriented. Diamond was only a sub-distributor, and they were picky. They passed on many of our titles.

Do publishers still need minimum sales to be carried by Diamond?

I don’t know. I don’t think we’re making minimum sales on every Uncivilized item. [Laughs.] But some things do, so I guess Diamond’s just letting us do whatever we do.

You remember the controversy in the late 1980s, when Diamond briefly refused to carry Yummy Fur because it didn’t make minimum sales. But then Diamond was bullied into carrying a comic featuring Ronald Reagan’s head on the end of a penis. [Laughter.]

Now and then, they had to be shamed into carrying good comics.

Tell us about another fall 2021 book, Matt Madden’s Ex Libris. Matt mentioned on his blog that you worked closely with him on the cover of the book. How much do you typically collaborate with artists on the design and contents of a book?

On the content, it was all Matt. I saw the book earlier, about a year ago, but then he came back later with a much more finished product. I gave some comments on these drafts, but they didn’t need much editing. He had his trusted readers he would talk to, who gave him feedback.

The person he’s married to would be the first “trusted reader.” [Laughter.]

Right! That’s one for sure. On the cover, Matt had an idea—he wanted a vortex, but he didn’t know how that vortex was going to play out. I put on my graphic designer hat and came up with different variations. I generated a lot of designs around with the idea of the vortex—more present, less present, more diffuse, less diffuse—until we got to a point where we both liked the design.

I saw some of the earlier rejected cover designs, but each led you to the final cover.

I have probably forty different variations on that cover. I’ll probably do a big post on the Uncivilized site about those designs in the future.

I imagine with “veteran” artists (Matt, Craig, Gabrielle) there’s less little editing involved. Is the same true with cartoonists’ first books, or…?

I’ve worked with artists who ask me to give them a lot more feedback, and I’m happy to do that. The artists you just mentioned are good at what they do—they’ll occasionally ask for some feedback on a specific sequence, but really, they just need me to confirm their instincts. Some artists are great designers—Craig is a great designer—so he doesn’t need a lot of input on the covers. He’ll give me a few variations, we’ll talk about it, but it’s all his ideas.

Then there are other artists less comfortable with the graphic design part, so we’ll talk about what image should be on the cover, and I’ll take it from there and build a cover design. It varies from artist to artist, which makes it fun for me. Sometimes it’s nice to get a complete project ready to publish, and sometimes it’s nice to give form to something more unformed.

Earlier, we were talking about AdHouse as an entity, and AdHouse is—was—Chris Pitzer: he would collaborate on the designs for AdHouse books. Is Uncivilized “just you” in the same way?

It’s just me. For a while, Jordan Shively was an associate publisher, and he brought a few artists and projects over from a small press he ran. That work bubbled up into Uncivilized. But now he’s doing his own thing, he’s writing for games and fiction, he’s got a T-shirt project. He wanted to focus on other projects, so he left about a year-and-a-half ago.

I do have interns. I currently have a publishing assistant, Az Sperry, who helps me with the basics. If we have files we need to put into InDesign…she takes care of that stuff. Aseret was in my publishing class at MCAD, and then she was an Uncivilized intern, and then I hired her. She designs books, and I give her feedback. She’s also been fantastic in helping the office get more organized.

But it’s mostly me in terms of editorial decisions.

Are there other Uncivilized books on the horizon?

There will be a new series coming out by this young cartoonist, John Grund, who was also an intern of ours, though he graduated from SCAD. His series is called West, and it’s this weird sci-fi/magical western with capitalist/communist undertones. [Laughter.]

The TV show Deadwood was obsessed with capitalism: individual entrepreneurs vs. mogul capitalism.

I didn’t see the show, but I heard that from others. The wild, wild west is the embryonic case of primitive accumulation, monopoly, and capital…John is handling these issues with a lighter touch than Deadwood. I’m pretty excited about West.

I’m doing another issue of Cartoon Dialectics, coming soon. It might be all about money. [Laughs.] We’ll see.

Your podcast definition of Bitcoin was the most lucid one I’ve heard.

And now the Uncivilized website takes Bitcoin! [Laughter.] You can buy comics with Bitcoin! I’m always interested in strange things like that—recently, I’ve been more anti-Internet, but I’ve moved past that… I see a lot of potential around crypto, but it’s still in its early stages. In a way, I am returning to the optimism I felt during the early Internet.