Alex Dueben's An Oral History of Wimmen's Comix includes authorial snippets from many contributors to the alternative, all-women's comic anthology Wimmen's Comix. Notwithstanding, one authorial perspective is missing from the article: Angela Bocage. Bocage was a prolific contributor to Wimmen's, participating—as artist, writer, or editor—in seven of the seventeen issues of the comic's run, almost all the issues that came out after the anthology's return in 1983 with issue #8.

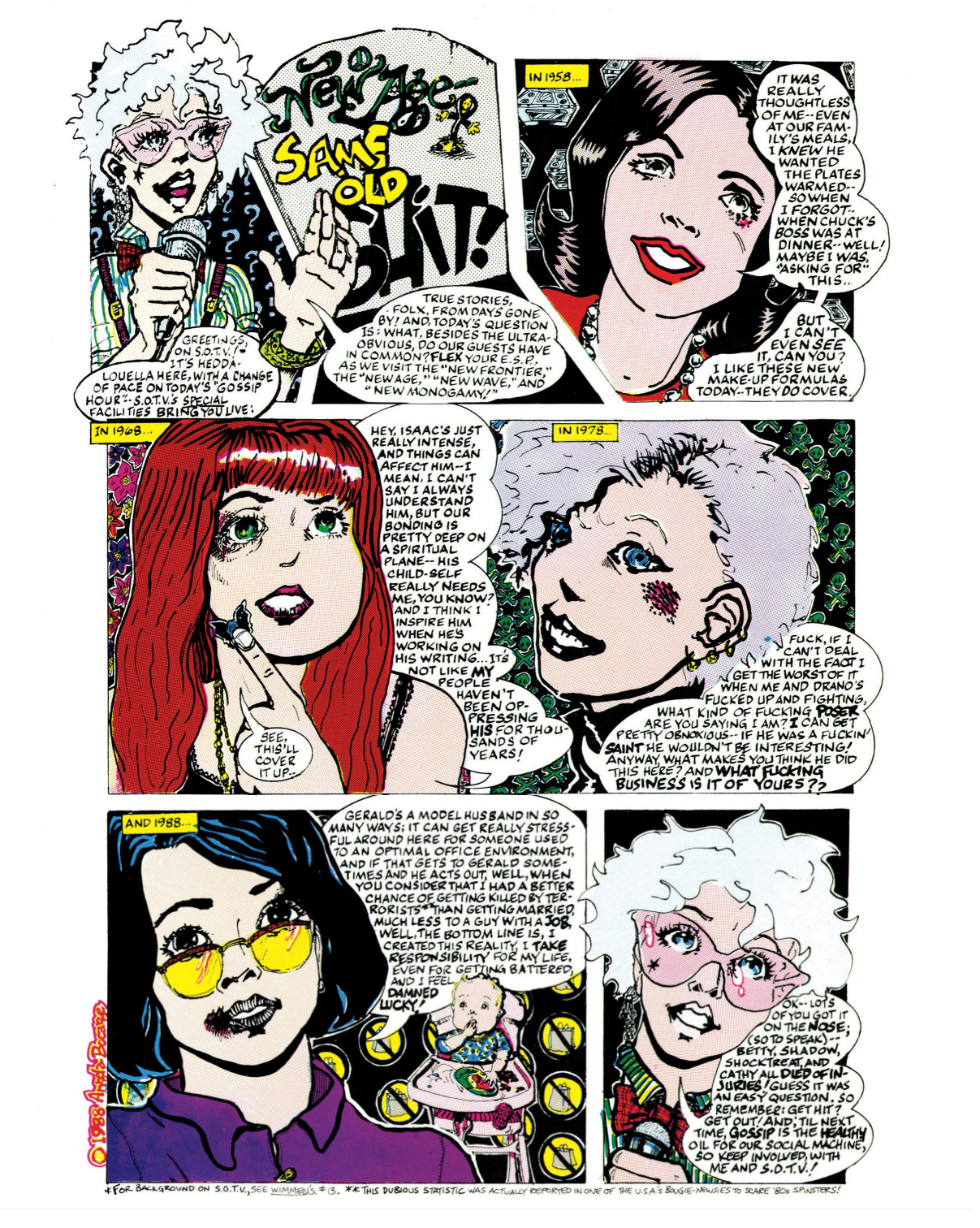

But Bocage's part in the alternative comic scene goes beyond her contributions to Wimmen's. In a San Francisco Examiner article on the scene in 1992, David Armstrong includes her as one representative of the "new new wave" of underground cartoonists who emerged during the '80s and '90s. (Armstrong lists Phoebe Gloeckner, Krystine Kryttre, and John "Derf" Backderf as three others.) Bocage has had comics in World War 3 Illustrated and the Fantagraphics-published Street Music. She also drew and wrote the story "The Estate Sale" for the comic collection Strip AIDS U.S.A.. Moreover, Bocage drew the syndicated comic strip (Nice Girls Don't Talk about…) Sex, Religion, and Politics! for the Bay Area Reporter.

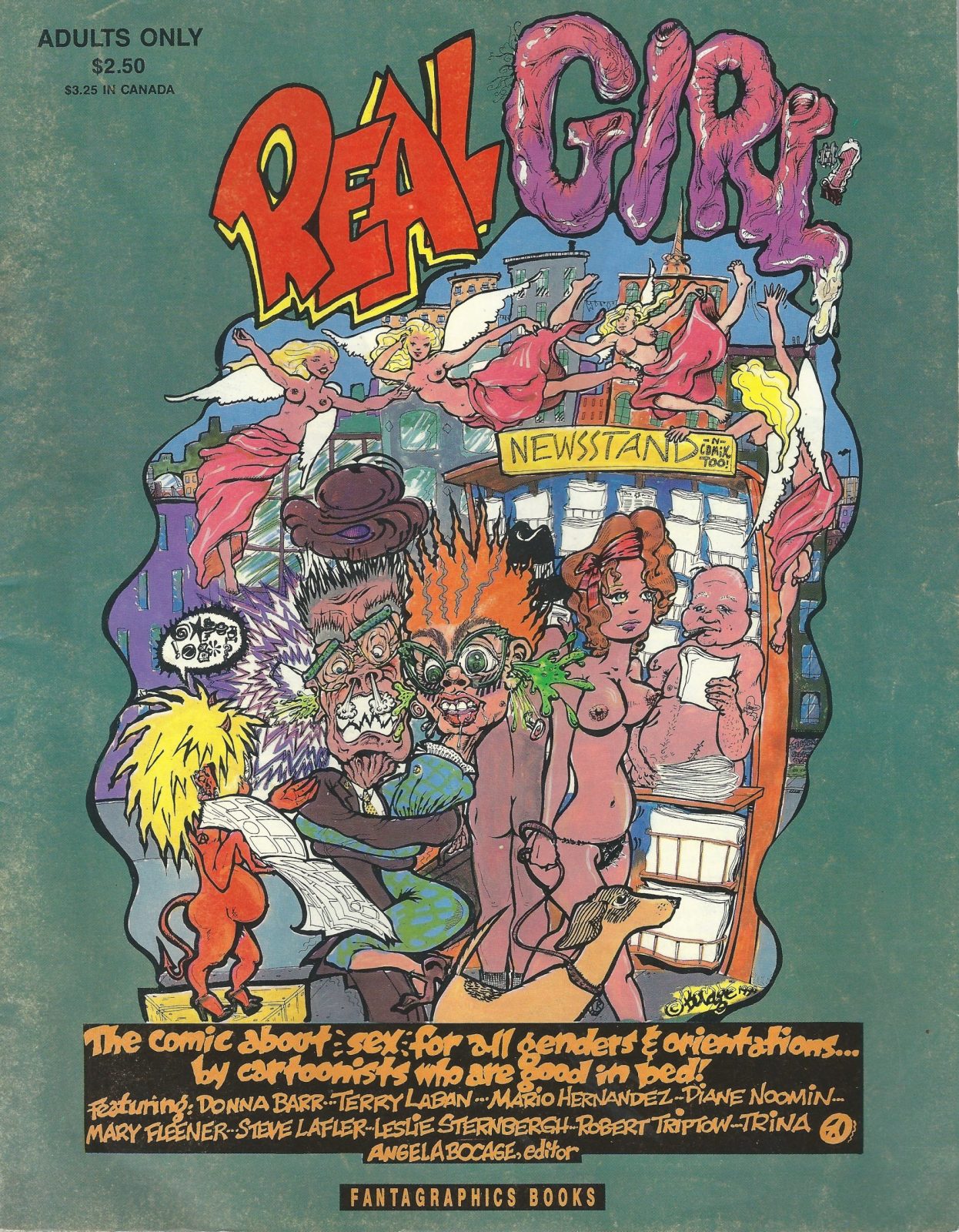

Yet no one has made a retrospective overview or academic analysis of her work. This dearth is a problem. In my interview with her, Bocage complicates the optimistic view of the Wimmen's Comix collective espoused by Leah Misemer, James Zeigler, and Rachel R. Miller—academics at institutions across the United States. With the release of the book The Other 1980s: Reframing Comics’ Crucial Decade in 2021, in which Miller's and Zeigler's works on Wimmen's appeared, detailed academic scholarship about the '90s underground scene (beyond Daniel Clowes…) will begin soon, and one comic that will likely become important is the Bocage-created (and Fantagraphics-published) anthology comic Real Girl, which Bocage edited from 1990 to 1996.

According to Real Girl's covers, the comic is "The comic about sex for all genders & orientations… by cartoonists who are good in bed!" And, abiding by the cover blurb, many of the stories included in the Real Girl anthology play with gender identity in a modern way. In issue #7's "Our Wedding Night", Bocage illustrates an unconventional sexual encounter wherein the woman in a heterosexual relationship uses a strap-on with and is gruff to her pantyhose-wearing husband. Issue #6 includes Anne D. Bernstein's story "Confused Things" in which "chicks with dicks" and "muscle bound women" frolic to the writings of Alexander Pope and Leonardo Da Vinci. Real Girl was a comic for all genders and orientations, but, due to the large number of stories dealing with lesbian sexual experiences and transgender women, the comic emphasizes the feminine experience more than the masculine one. Through Real Girl's focus on these unconventional but feminine gender identities, Bocage took the woman-dominated space of Wimmen's Comix and pushed further (with more male artists) the feminine sexual norms already stretched in the pages of Wimmen's. Even in Real Girl's title, Bocage's comic separates her work from the "Wimmen" who came before.

With increasing scholarly interest in the women-created and politically and sexually charged alternative comics of the '80s and '90s, I felt as though giving a voice to Bocage would add to current scholarship. The following transcript is a combination of a written-out Q&A with Bocage and a video interview.

-Edward Dorey

* * *

EDWARD DOREY: Do you feel that Wimmen’s Comix in the post-hiatus ['80s] years became less political, or were there still notable political elements?

ANGELA BOCAGE: There were some significant political elements, to use your phrase, in my period of Wimmen's Comix. One came in the form of a cogent challenge written by Andrea Natalie to the near-monolithic cishet POV of issue content. Another reality addressed by Andrea Natalie and several other artists in Caryn Leschen’s illness issue [#17] was disability.

[However,] like so many arts action groups of the times, the editorial collective of Wimmin’s followed the evergreen tradition that showing up was everything in terms of having a voice, and the people for whom showing up was easiest were those in the Mission and Noe Valley, adjoining neighborhoods of San Francisco where Caryn [Leschen], Lee [Binswanger], Trina [Robbins], Diane Noomin, Phoebe Gloeckner, Dori Seda, Krystine Kryttre, Rebecka Wright and I lived. Leslie Ewing, another out queer contributor who had a weekly strip in a SF gay weekly and was therefore one of our best-exposed members, often trekked to meetings from the East Bay. Sharon Rudahl and Trina were longtime friends, as were Diane Noomin and Aline Kominsky, so even though Rudahl and Aline lived in other parts of California, their views were always heard. This “show up, stay late, get it done” dynamic… goes a long way towards explaining the political narrowness of the post hiatus ['80s] collective, who were all white, overwhelmingly straight, and mostly well-off via husbands or families.

By those years of the mid-‘80s through ‘90s, as recounted in Susan Faludi’s excellent Backlash [1991], there was a fierce media push encouraging people to consider feminism over and its proponents sad, unstable, childish, and, worst, UNATTRACTIVE women, a tactic as old as Midge Decter’s 1960s rhetoric described by Joan Didion in The White Album. Careerism as a sop to women had taken hold to the extent that even mildly liberal Doonesbury had Joanie Caucus commuting in her sneakers and anklets. However, no one outside certain specialized fields (e.g., law, social science) was talking about the insidious dynamics of gender-based violence. With that possibly interminably boring background, I can explain what I was doing [in the Wimmen's collective].

I’ve read, loved, and created comics all my life and have also been impacted by a giant tangle of feminist issues! If you’ve seen my contributions to Street Music and World War 3 Illustrated, you know that I witnessed the brutal gaslighting and beatings of my mom by my stepfather and later experienced similar at the hands of my poor broken depressed mom before her needless, poverty-related death from panhypopituitarism (now known to be among battering sequelae) when I was 11. In today’s parlance, I have a ridiculously high “A number.” It’s a wonder I function at all!

After returning to comics in undergrad at Santa Cruz, I turned back to painting and illustration in the early '80s, working temp jobs and in Silicon Valley tech recruiting to survive. My art appeared in urban gardening posters, zines, protest banners, and the Bay Area Center for Art and Technology magazine Processed World, an early zine that had a lot of good articles about how work, society, and social relations didn’t meet human needs or planetary needs. I was on the media committee for the Bay Area Coalition for Reproductive Rights. Making art for social good was the most fun I’d ever had until I had kids! These snapshots of my life, plus having a university education where I learned about international conflicts in South Africa and El Salvador, class war, and the history of civil and women’s rights, may explain the political advocacy in my work.

I wanted to explore real life and real social conditions. I did a piece about the plight of incarcerated people denied education for WW3 Illustrated, and a child abuse and identity piece published in both Street Music and WW3 Illustrated, and continued to devote myself to zines, activism, and most of all to my baby son, Robin Black. Conversations about sexualities and private and public identities with Dana [Andra, then known as Mark Burbey] led to my decision to start Real Girl, which not a lot of people understood, but which I think fulfilled some of the promises Wimmen's Comics never did.

In the Wimmen's collective, there existed some internal conflicts among individuals over approaches to art, politics, and editorial policy that were quite deeply rooted in the real-life conditions of members of the group, a lot of strange interpersonal/intergroup conflicts always simmering. One kind [of conflict] paralleled the feminist Sex Wars of the time; those of us who were more punk—Dori, Krystine, Phoebe Gloeckner and I—were perceived as more “bad girls”, and laughed about it. Phoebe, like Dori and Carol Tyler, was punk, world-travelled, and is a brilliant artist and storyteller; they also studied art within academia and had an art historical perspective not seen quite as often in comics back then. The recollections above represent very briefly a few of the class/political/sexual/educational fault lines I perceived in the collective. With all the forces ranged against us, I’m proud of us for getting all those anthologies done, edited, and published.

The issue arising from these fault lines that I struggled with the most was whether it was desirable to publish everything we received from artists identifying as women, or whether some pieces could be rejected if we reached a consensus they were irrelevant or ineffectively executed. Because of the dearth of women-welcoming venues, we almost always erred on the side of inclusion. I don’t think we were paid anything close to the going page-rate, or whether we may not have been paid at all sometimes, so it wasn’t like anyone was benefiting financially, but I can say that I and the people whose opinions I knew did WANT the comics audience and the public to see a wide variety of women’s comics. We wanted to be a library of possibilities, on one hand, but also chafed at only being able to do very short stories, because apparently no one was offering to publish longer books. This problem was a difficult one for me because I thought both positions were good: if we edited more selectively, we’d have a more visually and literarily appealing comic book, and possibly more pages for ourselves and artists we loved. On the other hand, trying to lift up all women cartoonists and keep international lines open seemed the right thing to do! Of course, in practice, artists that produced beautiful and meaningful five- or six-page pieces often did get allotted pages, especially if we liked them, so that was one chasm between stated ideal and actual practice.

In Leah Misemer’s article “Serial Critique: The Counterpublic of Wimmen's Comix” [Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, Volume 3, Issue 1, Spring 2019, pp. 6-26], Misemer contends that Wimmen’s, due to its anthological nature and open invitations to new artists, was a forum that allowed for the creation of a “counterpublic” at odds with the mainstream. Do you feel that this is true? Moreover, according to the comic scholar Dr. Margaret Galvan, you identify as bisexual. If so, did Wimmen’s feel inviting if it was a “counterpublic”?

We had a counterpublic, I think. The revival or post-hiatus Wimmen's Comix was first published by Renegade Press, the imprint led by Deni Loubert. Renegade [Press] started to have a presence at conventions, and this helped us develop an audience within the comics-reading audience. I worked for a while for Good Vibrations reviewing erotica and was active in sex-related zines Slippery When Wet and Frighten the Horses, so my work brought a broader community in. As for support for my bisexuality, I had the impression that, since I was from 1990 raising Robin and daughter Jasmine with a guy, Jasmine’s biodad, that I was not really considered queer by the Wimmin's gang, but I was accepted fine in queer circles. In 1989 I started chronicling the AIDS epidemic in (Nice Girls Don’t Talk about…) Sex, Religion, and Politics! in the Bay Area Reporter with my close friend Michael Botkin, who wrote the popular "HIV Watch" feature for [the Bay Area Reporter] and did various pieces for Gay Comix during Robert Triptow’s editorship.

Lee Binswanger has noted that she was strongly inspired by the work of M. K. Brown in National Lampoon when she got into underground comics. And Caryn Leschen mentions in "An Oral History of Wimmen's Comix" that she was inspired by Aline’s, Trina’s and Lee Marrs’ work before joining Wimmen's. Notably, neither of these women came into comics with what many consider the “standard” kind of comic, or superhero comics. Leschen notably mentioned Spider-Man with distaste during one interview.

However, you seem to have inspirations that were less underground or in magazines. In a blog post, you mention hiding Thor, Batman, Daredevil, and Spider-Man comics in your quote-un-quote horrible math books. Currently, your [private] Twitter feed contains occasional references to superhero comics or superhero-comic inspired media, and your story for Rip Off Comix #27, or “Love is the Drug”, has a vaguely superheroine-like figure battling against Christian Reconstructionists in a nude and sexual but not completely dissimilar way from a superhero.

My question is, therefore, what were your major inspirations when getting into comics, and did these compare to many with whom you worked while editing, drawing, and writing for Wimmen’s in its post-hiatus ['80s] years?

My main inspirations come from being the daughter and granddaughter of artists. And, from before I could talk, being shown art books from all centuries, from twentieth century [art] to cave art. So my thing is to have the most possible [number of inspirations]. Who would do comics without knowing the best of all comics ever? Who would do comics without knowing Winsor McCay or Krazy Kat? Also, as a very small child, I loved Al Capp’s and Chester Gould's work. Their ink lines entranced me. I wanted comics to be able to draw in all the influences and create from a knowledgeable perspective. So I wanted to see cartoonists like Caryn Leschen [in Wimmen's because she] drew on her travel experiences that were not just American. And Lee [Binswanger] is a unique artist, almost Zen in her observations of life. There were amazing women cartoonists who influenced a lot of us, but one bond between Dori Seda and me is that we had [an] art history background. Within this context, I appreciated a great deal about superhero comics without ever feeling overawed by their market-ubiquity in the '70s-'90s.

Did you see that there were any differences in the artistic or philosophical inspirations between the post-hiatus ['80s and early '90s] and the pre-hiatus ['70s] artists in Wimmen's Comix?

My main thought about that is that I think that the pre-hiatus artists were more overtly and specifically political.

In art schools during the time that I grew up, political art was trashed. People would say, "if you're a good artist, you don't want to go into that political stuff. It has no subtlety; it's not intelligent." I later began to see that this was a crock because you could bring your artistic perceptions to any subject, whether political or not.

I think that the pre-hiatus artists got that! They had more fire and anger, and I don't think that we had that so much in the post-hiatus.

You note that your comic Real Girl fulfilled the promises that Wimmen’s never did. The promises on the front cover of Wimmen’s #1 are “Sex, Revelation, Psychotic Adventure and More..." Yet the scene to you had a fault line between the “bad girls” and the rest of Wimmen’s. Was your work censored in any way? Furthermore, was the work of others censored?

No, I don't recall my work being censored, and I don't recall the works of others being censored, but others may have had a different experience. Also, we have to look at what we mean by censorship. As an attorney, I see it as state action more than the critical push-pull as any art form emerges. There are [several] legal questions that come up. However, when I was the editor of Wimmen's with Phoebe [Gloeckner]: there was argument, and critique, and fierce disagreements about a piece including a young girl’s sex fantasy. Debate and editorial choices aren’t censorship, but in the moment it feels like a struggle.

In what ways did Real Girl answer the promises that Wimmen’s never did?

By allowing a longer page length. So artists could develop their stories more. My work suffered, and a lot of other people's work was not as good when we had to cram everything into one or two pages. It [the shortness of the page length] was not an easy question to resolve because we wanted to put as many people in the book [Wimmen's] as possible.

What was editing the “3-D issue,” or issue 12, of Wimmen's like? Did you feel supported in your role?

It was wonderful. It was my first experience with the collective, and I was getting to know everybody. For me, it was discovering all these comrades. I had not known that many women artists.

How did editing that issue compare to assistant editing issue 15, or the “Little Girls” issue, with Phoebe Gloeckner?

By issue 15, there was more of a reification of some people as "bad girls", and I felt like that I was identified as a "bad girl", and realized I was fine with it. There were controversies. I was mad because we wanted to include the abovementioned piece that other people didn't like. Phoebe is so strong, and brilliant, and amazing, I can't imagine anyone winning against her. I was annoyed with Trina [Robbins] at that time. I love Trina; she is a good friend, but I was very annoyed with her at the time.

Do you feel that the Wimmen’s crowd accepted transgender women?

I don't remember transgender women sending work or approaching the collective, so I don't have any experience with the Wimmen's editorial collective having a position [against transgender women]. However, back then there was a horrible TERF-y aspect of feminism that did reject [transwomen]. Society in general [also] treated transwomen horribly. But I don't remember [issues with transgender women] coming up, or I would be happy to speak to it.

Your publication, Real Girl, continued after Wimmen’s ended. Trina Robbins, in her introduction to the complete Wimmen's collection, argues that [Wimmen's cancellation] was due to sexism in the comics market: primarily male comic book store owners refused to stock an all-women’s comic, even if it sold well. What do you feel ended Wimmen's?

I think that it was more acceptance of women that ended Wimmen's. We didn't have to do our own little two-page comic because we could do our own comic books. [There was an] ease with which I proposed a book like Real Girl through Fantagraphics and they said, "Sure, go ahead and do it!" As long as you kept offering to pander to the male gaze, they [the comics industry] were fine with you. So I did a lot of overtly sexy comics because I knew that that would not get me censored anywhere, get me not published. And later, in the LGBTQ community, I could do anything. I think that the fact that women created our own inroads into acceptance and publication [ended Wimmen's]. [It was also] lack of knowledge of the industry that kept women out [of comics] previously. There were always women at Marvel; there were always women behind the scenes. But when more little girls that had grown up reading comics realized that there was a way to get into the industry, they did.

I have issue #8 of Real Girl right now, and, in it, there is a short story "Educating Lance", which is about a young yuppie, Lance, who finds intersexual fairies who torture Lance until he becomes in love with them. And the story is by David Ethan Gilden and illustrated by you. I was wondering this: was "Educating Lance" playing to the male gaze?

Perhaps, but its intent was to introduce more kink content because, while kink content existed in undergrounds and more explicit comics in [the '90s], there was not, outside of the zine world, a lot of kink content. I knew that a lot of people were interested in [kink content] and thought it could be a lot of fun.

Some people have criticized that story and hated that story so much that I was like, "Ok, you're protesting a little bit too much." David Gilden had forced effeminization kinks that he liked to explore in life. ["Educating Lance"] was an example of [that kink]. [That kink] bothered a lot of people.

["Educating Lance"] was not a pandering to the male gaze; [it] was a desire to put more a variety of experience into Real Girl. And this kink was not in mainstream comics at that time or [the] underground as it existed then. I think that Real Girl's time period was not the same time period as undergrounds. I think [of Real Girl's time] as post-underground, [and Real Girl offered] a new approach to sex comics.