"Herriman was talking about race and identity — as profoundly as anyone has, in my opinion — but I never see that as his big “Topic.” It was just part of his world, and the world he created, even if others were slow to recognize it."

-Michael Tisserand

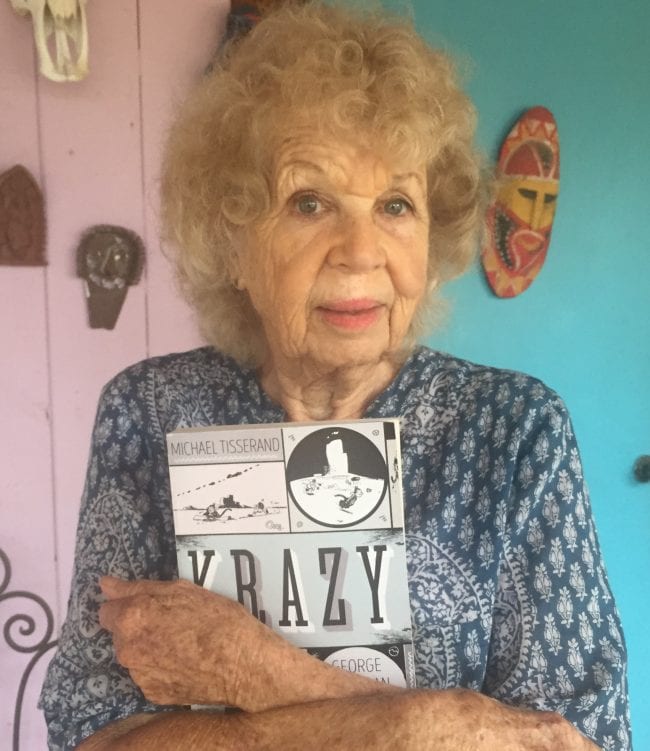

The first time I saw Michael Tisserand, he was walking up my doorstep, holding what appeared to be a red brick by his head, almost -- but not quite-- in a throwing pose. Turns out the red brick was the recently released Library of American Comics collection of Krazy Kat dailies for which he wrote the introduction, and it was a gift (aren’t all bricks gifts in Herriman’s world?).

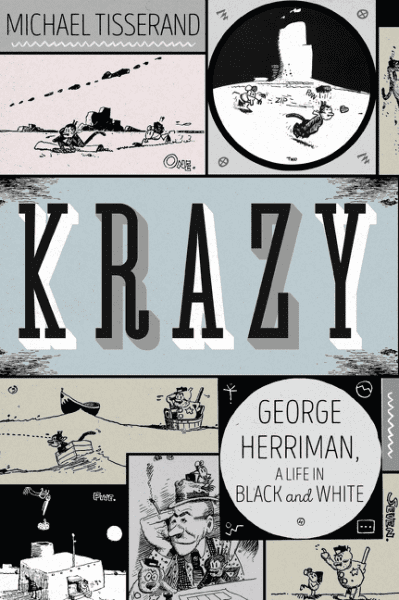

In early December 2016, HarperCollins will release Tisserand's long-awaited book, Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White. The book, over 500 pages in length, offers the first detailed biography of the man many regard as the greatest cartoonist of the twentieth century. Chris Ware has spoken highly of the book, observing: “Michael Tisserand’s Krazy draws back the curtain on the one [Herriman] who’s been with us all along.” The book has drawn an early favorable review from Kirkus which states, in part: "Essential reading for comics fans and history buffs, Krazy is a roaring success, providing an indispensable new perspective on turn-of-the-century America."

Michael Tisserand currently lives and works as a professional writer and amateur chess coach in New Orleans, George Herriman's birthplace. His books include the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award-winning The Kingdom of Zydeco, originally published in 1998 and reissued in November 2016 from Arcade and 2007’s post-Katrina story Sugarcane Academy: How a New Orleans Teacher and His Storm-Struck Students Created a School to Remember (Harvest). He has also contributed an essay on George Herriman to Krazy Kat, A Celebration of Sundays (Sunday Press, 2010). He also wrote the introductory essay for LOAC Essentials Presents King Features Volume 1: Krazy Kat 1934 (IDW Library of American Comics, 2016).

Michael encouraged a peer-to-peer exchange that led us away from a question-and-answer routine into a freewheeling two-way discussion, hence the “konversation” format. I’ve had the occasion to visit and work with Michael in Seattle. In my home, he spotted a recently released biography of Warren Zevon I was reading and asked me, “You like Zevon?” When I said yes, he told me about how he and Zevon were part of the same circle of people in Louisiana. Visiting with Michael is like that. You never know where the “konversation” will go, but it’s guaranteed to be surprising and interesting. Tisserand is a man of many stories, and he gets around. Whether it’s driving across country to hand deliver an advance copy of his new book to George Herriman’s granddaughter, or jumping on a plane to capture an interview with a newly located cartoonist from long-ago (see his Comics Journal piece “Pete, the Rookie” here), Tisserand is a man on a mission.

Part one of this long interview explores the genesis and methodology of Tisserand’s book, his background, and George Herriman’s early years. Part two of this interview will traverse Herriman’s middle and later years.

This interview was conducted in a series of sessions in October, 2016. When Michael Tisserand and I first sat down to talk, the American presidential campaigns were in full swing.

Paul Tumey: Thanks for doing this.

Michael Tisserand: Are you kidding? Been looking forward to this all week. Watching two hours of campaign news last night, all I could think about was how much I was looking forward to talking comics with Paul.

Paul Tumey: Me too, brother, me too. Okay, here we go. You are a professional writer and journalist living and working out of New Orleans, Louisiana. You’ve written acclaimed books on zydeco music and the aftermath of Katrina. You’ve told me you spent about eight years writing Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White. What led you to the Enchanted Mesa and the world of George Herriman?

Michael Tisserand: I actually went back and looked at my emails and it was ten years! I was originally dating back to my first trip to Monument Valley, to the Wetherills' gravesite in Kayenta, and to my meeting with the Wetherills' grandson and seeing Herriman's entries in their old lodge book. That's when I realized my work was truly underway.

Paul Tumey: What first put the idea in your mind to write a book on Herriman?

Michael Tisserand: I had started research when I was editor of Gambit Weekly, the alternative newsweekly in New Orleans. Although it was understood that Herriman was a New Orleans native, the details were murky. I wanted to know more. But all I'd done there was order a complete set of Inks on eBay. My last act upon leaving the office before Katrina was to move that stack to the desk, where it thankfully stayed dry.

Paul Tumey: For those that don’t know, Inks is the Journal for the Comics Studies Society, recently revived after a long hiatus.

Michael Tisserand: Yes. A great journal. I had that first set of Inks, but that was about it. The year after Katrina, I was living in Chicago, and I was able to see the Masters of American Comics exhibit when it stopped in Milwaukee. I remember was carrying my son around the Herriman room, reading the comics to him, and laughing with him at the sight of the thumb of conscience pressing down on Krazy Kat. That’s also when I realized the best way to read Krazy Kat is out loud. Anyway, I'd just finished my second book, Sugarcane Academy, and when returned home that day I told my agent I wanted to write Herriman's biography.

Paul Tumey: I love the parts in Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White where you describe the cartoons Herriman and others drew in the Wetherhill's lodge book. We can talk more about that later on. Was the Gambit piece on Herriman ever completed and published?

Michael Tisserand: It was not! And I made off with the Inks magazines, too!

Paul Tumey: Did you cover any other comics guys in Gambit?

Michael Tisserand: One of my favorite things about editing Gambit was being able to bring more comics into the paper. I commissioned Harvey Pekar to write musician biographies that featured art by Joe Sacco and Frank Stack, among others, and I was always shaking my head about actually getting to work with these legends. And I was able to commission work by local cartoonists whose work I loved, such as Bunny Matthews and the late Greg Peters.

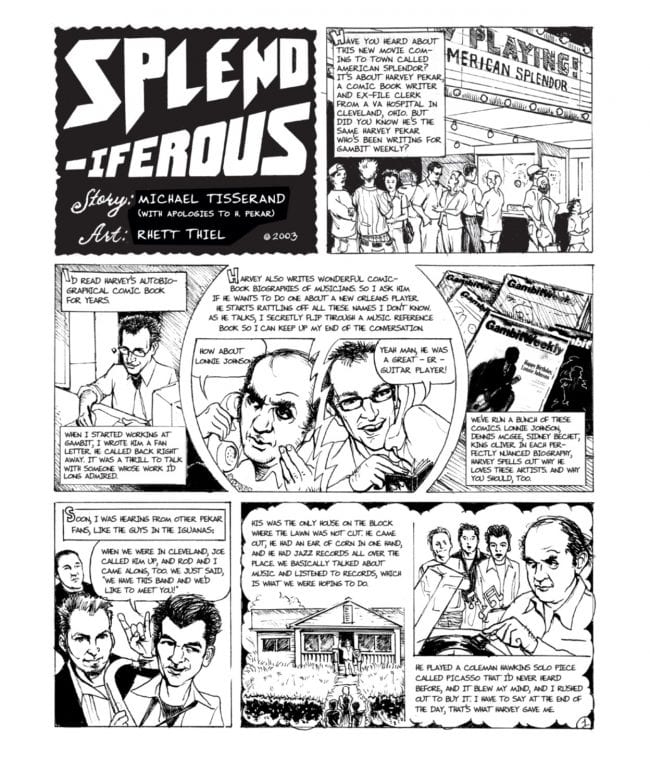

Paul Tumey: Kid Ory, Lonnie Johnson, Clifton Chenier… wonderful work by Pekar and the various artists. Pekar ran them in some of his collections. You know, I’ve read some of Pekar’s text jazz articles – they are very dense and scholarly – not at all like his comics writing, except for a sort of OCD aspect. I love “Splendiferous,” the two-page comic you wrote and Rhett Thiel drew about working with and knowing Harvey Pekar. How much did you know about comics coming into your Herriman biography?

Michael Tisserand: Harvey liked that comic too, happily. It was and is my only attempt at writing a comic, and before starting researching Herriman, I’d never written seriously about comics, either. I've read and loved comics since I was a kid, however. I used to beg my mom to let me spend the day by myself at the Willard Library in downtown Evansville, Indiana. There I discovered the wonders of the 741.5 section, which I can still remember being on the bottom shelves in a back corner of the main room of this old creaky library. I would just sit on the floor there and go through all the books I could find.

Michael Tisserand: Harvey liked that comic too, happily. It was and is my only attempt at writing a comic, and before starting researching Herriman, I’d never written seriously about comics, either. I've read and loved comics since I was a kid, however. I used to beg my mom to let me spend the day by myself at the Willard Library in downtown Evansville, Indiana. There I discovered the wonders of the 741.5 section, which I can still remember being on the bottom shelves in a back corner of the main room of this old creaky library. I would just sit on the floor there and go through all the books I could find.

Paul Tumey: 741.5 has always been a magical number for me too.

Michael Tisserand: 741.5 was amazing! I found the old comics anthologies by Bill Blackbeard and others. There was simply nothing else like old Katzenjammer Kids or Dick Tracy comics. Then when I went through all of those, a librarian showed me how to read old newspapers on microfilm, and I zoomed through the news pages to the funnies. I wasn't, however, drawn to animal comics. I liked stories about people, and any allegories were lost on me. For the most part, I just became obsessed with Peanuts, and with Charlie Brown.

Paul Tumey: Schulz is a good place to be obsessed, I think. Peanuts can lead you to the rest, like a gateway drug. Sort of like discovering older American music forms by starting with an obsession with Bob Dylan. The great artists seem to lead one backwards in the lineage.

Michael Tisserand: Right! And as with Dylan and folk or the blues, discovering the old comics also make you appreciate all the more how Schulz was building on the tradition.

Paul Tumey: Speaking of Peanuts, I wanted to ask if David Michaelis' lengthy 2008 biography, Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography, was an inspiration or model for Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White?

Michael Tisserand: I certainly hoped to make something as readable as Michaelis’ book. The masterful integration of comics in Michaelis' narrative was definitely a model, though I quickly realized I couldn’t even run a daily strip across a page of the Herriman biography and have it be an enjoyable experience to read.

Paul Tumey: Peanuts works well reduced in size. It was part of the strip’s success, launching when newspapers were allotting less and less space for daily comic strips and still one hundred percent readable in smaller versions. In many cases, American newspaper comic strips created prior to the 1940s and 50s don’t lend themselves well to size reductions. I’d imagine shrinking Krazy Kat panels from the 1930s would turn Herriman’s sumptuous, dense pen work into black blobs.

Michael Tisserand: They do. I found that out the hard way. The major difference from Michaelis’ book, of course, is that Michaelis could base much of his work on extensive interviews that he conducted himself, which was how I was used to working, as well. I'm not a trained historian, so I had to teach myself how to construct a narrative largely based on letters, newspaper articles, and official records like census reports and city directories. The problem I didn’t have, however, was contending with personal narratives that might reflect different experiences, which as The Comics Journal covered, was a major challenge that Michaelis faced.

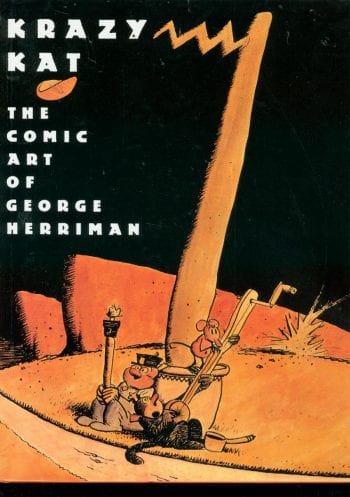

Paul Tumey: That leads me to my next question. For almost a hundred years, people have been writing about the life and work of George Herriman. Gilbert Seldes sang his praises in 1924. In 1986, Patrick McDonnell and Karen O’Connell published Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman. This has been regarded as the definitive book on the subject. In addition, there's been a library's worth of introductory essays to the various reprint volumes of Herriman's work published over the years by Bill Blackbeard, Richard Marschall and others. One would think all the stories were told, and the subject was exhausted. And yet, in 2016, you’ve given us something new and, I think, quite magical: a 560-page, detailed biography of Herriman. Can you talk a little more about the research methods you used to deepen and broaden Herriman’s story? How did you dig all this stuff up, man?

Michael Tisserand: Patrick and Karen's work was certainly a foundation. Their writing about Herriman is beautiful and timeless, as is Gilbert Seldes', actually. But of course none of these writers had the Internet to make it possible to do a more exhaustive search.

But I started there. Patrick and Karen very generously shared all their original research with me, as did many others. When I started out, I was concerned that the comics scholarship community would be suspicious of an interloper, but it was just the opposite. The generosity has been overwhelming.

Paul Tumey: So you built on the work of others?

Michael Tisserand: Yes, exactly. Rick Marschall invited me to his house and beneath a painting by Rudolph Dirks, answered question after question about early newspapers and syndications. I had a most wonderful day with Bill Blackbeard. Tom Inge had once pursued a biography of Herriman and shared with me the letters and other information he'd received, which then led me to contacting Russell Myers, who shared a recorded interview he’d conducted with Bud Sagendorf that focused just on Herriman. Jeet Heer took me under his wing and provided copies of his copious files, and engaged in conversation after conversation about Krazy Kat. Same with Art Spiegelman and Chris Ware. Brian Walker, who co-curated the show that sparked this book, opened up his archives and even invited me to lunch with his father, Mort Walker, and Jerry Dumas. One of my happier afternoons of research!

And there were so many more. I learned the extent to which cartoonists are scholars of their art. Not only do they possess the knowledge, but in many cases, they own the historical treasures such as old letters and inscribed pieces of art that are necessary for telling the story.

Paul Tumey: All of those people are awesome to have in your corner, that’s for sure. There is such a generosity and kindness in the comics community. The Internet has been a game changer for cultural history, and certainly in comics history work – it’s brought us all closer. On the other hand, there are so many leads to follow!

Michael Tisserand: It can certainly seem endless at times. One of my writing gurus was the late alt-weekly editor and New York Times writer David Carr, and he instructed reporters to "avail themselves of all available knowledge" before writing about a topic. Which I did, to the best of my ability. Which also helps explain the ten years.

Paul Tumey: Your book reaps the benefits from that investment of time. It’s loaded with interesting details about Herriman’s work, life and times -- and that really makes it all come alive for the reader. It’s very satisfying. The archives and resources now available on the Internet open up lots of unprecedented opportunities that scholars didn't have before – but with that access comes a significant lengthening of the development cycle for these projects, I think. There’s a lot more paths to explore, and that takes time. But it can lead to some marvelous new discoveries. Can you give an example of a trail you followed that led to a cool new discovery?

Michael Tisserand: Just for one example, using the network of generous cartoonists, scholars, collectors, as well as academic and auction house archives, I made a list of all gifts of comics and comic art that Herriman had given people over the years. Then I conducted searches on the names of all the recipients. This is how I found Boyden Sparkes' interviews with Herriman and other cartoonists, which are archived at Syracuse University, and helped me tell the story of Herriman's early newspaper years in New York, as well as his life in the late 1930s when he was visited by Sparkes.

Paul Tumey: The Boydon Sparkes interviews is an exciting find. But, I know you didn't just sit at a computer. You actually traveled all around to explore obscure archives and meet various people. In the back of the book there's a list of people you interviewed. I know you connected in particular with Herriman's granddaughter, Dee Cox.

Michael Tisserand: My first call was to Dee Cox, for obvious reasons. At that point I didn't know her at all, and didn't know how she felt about discussing her family background, and all the new information about the family's life in Creole New Orleans that I was uncovering. I called her and asked if we could talk about her grandfather, and her immediate response was, "My favorite subject!" She's an artist herself and -- like her grandfather -- a very well read individual. She’s been immeasurably helpful and getting to know her has been a real highlight.

Paul Tumey: I have to ask: did Dee Cox happen to have a cache of previously unseen material and art of her grandfather’s? I would think there could be letters or diaries, even. The mind reels!

Michael Tisserand: No, and Patrick and Karen had met her long before I did. But she shared what she had, and of course, her personal memories were most precious.

I recently attended a talk by the writer Erik Larson, in which he described his process of determining whether or not there is enough material on a topic to merit a book. It's probably good that I didn't attend that talk before I started this research, because I would have had to admit that the material was pretty scarce. I quickly realized that I wasn't going to find a single rich trove of material. Dee Cox wasn’t going to open a closet to reveal a stack of Herriman diaries.

Paul Tumey: Oh, well.

Michael Tisserand: That’s when I realized I would have to patch this book together from lots of little bits and pieces. Which meant travel, in addition to lots of time spooling out the microfilm. But it was George Herriman. One can’t mess around when trying to tell the story of George Herriman. I felt a deep sense of responsibility. So our family vacations centered around Arizona for a few years, and I found a way to get to New York and California to seek out City Hall records, and I had a lot of help from people willing to show me how to access these records.

Paul Tumey: Yes -- I know exactly what you mean – and I appreciate the level of commitment a project like this requires. Bill Schelly, Harvey Kurtzman’s biographer, told me he stepped up his exercise and took vitamins and supplements to make sure he was as smart as he could be while he wrote Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created MAD and Revolutionized Humor in America.

Michael Tisserand: Didn’t think of that! I just drank more coffee.

Paul Tumey: Bill Schelly clearly felt the same deep sense of responsibility as you. I've been working on a biography of Jack Cole now for a while. As far as I know, Cole didn't give an interview and there really isn't much available about him. I think, in the case of a lot of these early 20th century cartoonists, you really have to dig deep and find lots of bits and pieces and be very clever to weave together a solid narrative. What you’ve managed to do in restoring Herriman’s story is kind of like an art specialist taking a dull, darkened hundred-year old canvas and using their techniques to reveal a great painting underneath. From reading Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White, I know you managed to find and speak with some people who actually knew George Herriman. I think that adds a lot to the narrative.

Michael Tisserand: Yes, Herriman died in 1944, so I was delighted – amazed, actually -- to find so many people who actually spent time with him! Most of these came from Harvey Leake, who is the family historian for the Wetherills, Herriman’s friends in Arizona. For example, Herriman signed a page of the guest registry with a note about the Roach family, and he drew and named three little cockroaches.

Paul Tumey: Ha!

Michael Tisserand: I found out that two of those cockroaches were the nieces of movie producer Hal Roach, and they had traveled with their father, Jack Roach, and Herriman, to Arizona. And that both women were still alive and healthy and filled with warm memories of their time with the man they knew as "Uncle George."

Paul Tumey: When I was reading the first chapters of your book, I was struck by how far back in time you had to go to tell Herriman’s story. Usually, biographers start with the parents of their subject – or, in some cases, the grandparents. But, you go back to the winter of 1816 and begin with Herriman’s great-grandfather. Why was it necessary to begin the story of the cartoonist George Joseph Herriman, born in 1880, so far back in time?

Michael Tisserand: I knew I was taking a chance. Certainly few people can pull that off the way Robert Caro did, when he started his multi-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson with descriptions of the soil and grass of Texas. I was fascinated by Herriman’s family story, but I asked myself repeatedly if general readers would share that fascination. Then when I dug into the records and found riots and seances and Jelly Roll Morton and all the rest, I knew I had to tell it. I found that understanding that family history also helped me better understand one of the central themes of Herriman's life: his race, what it means, what it might have meant to him, what it means to his comics, and what it means to us.

Paul Tumey: Having that perspective from reading your biography on Herriman’s life massively expanded my understanding and appreciation of his work. I have to admit, I was a bit daunted at first when I realized there was a chunk of early family history to read before our man comes onto the scene. But you know what? After a page or two of pouty grumbling, I was totally captivated – the stories are great, and you did a nice job of telling them. And later, I realized how valuable that perspective is – it’s the foundation for understanding the deepest levels of Herriman’s work.

Michael Tisserand: When I learned more about his family, I understood a bit more not just the pressures he must have felt in passing for white, but also the strange, unsettling feeling it must have been to identify with a group of people historically known as Free People of Color, or Mulatto, or Creoles ... a group that constantly was seeing its very identity being changed legally and linguistically and culturally. And then for Herriman to work in a genre so deeply influenced by the masks of minstrelsy! When I read a classic Krazy Kat line such as “lenguage is that we may mis-unda-stend each udda,” it seems pretty clear that Herriman had a deep understanding of what we now consider to be modern notions of the slipperiness of language and a sort of permeability of identity.

Paul Tumey: Once you become aware of this overarching theme in Herriman’s life, it seems to be the Rosetta Stone for what’s informing and driving Krazy Kat, and some of Herriman’s other work.

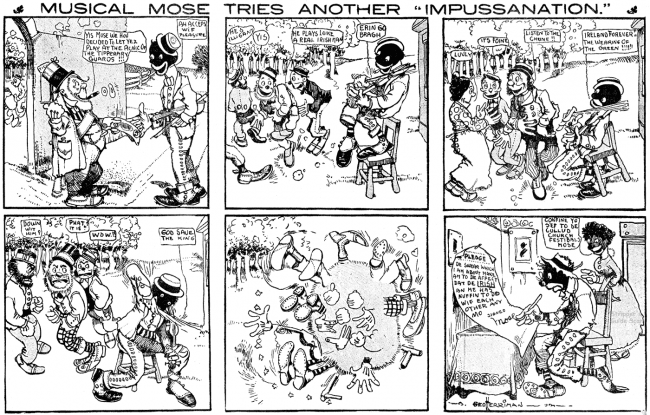

Michael Tisserand: Of all of Herriman's short-lived early strips, Musical Mose gets the most attention, because it offers such a brutal view of race and racial passing. It's about a black man trying to make a living as a musician by impersonating other ethnicities. Compared to Jimmy Swinnerton's Sam comics, which I love as much as I know you do, and which also uses a black protagonist to mock hypocrisy and absurd social behavior, there's not much laughter in Mose. It's not hard to see how Herriman couldn't sustain the storyline past a few episodes. Years later he'll recast some of the Mose scenes with Krazy Kat and Ignatz.

Paul Tumey: I think the identity theme particularly looms large in The Family Upstairs, later called The Dingbat Family. The main characters, and the reader by default, are always trying to learn the identity of the mysterious family that lives upstairs. It’s never revealed, which gives the whole thing an existential, Waiting For Godot aspect. I always saw The Family Upstairs as a sort of metaphor for the comedy and misadventure inherent in an obsessive search for God, although the strip itself is pure screwball, and blessedly so!

Michael Tisserand: Krazy Kat gets compared to Waiting For Godot, but I had never read The Family Upstairs that way! I think it’s a great way to approach it. Herriman would later dismiss it as just another failed strip of his, but I laugh out loud at The Family Upstairs probably more than any other Herriman strip, except maybe Baron Mooch. The parade of characters going up and down the stairs, and in out of that upstairs doorway, is endlessly entertaining. He throws so much into those scenes. It’s another example of Herriman playing variations on a theme. But you're right, there's a great mystery of identity at the center of it. Plus, throughout his life, Herriman was living in places where African-Americans weren't allowed to own or rent property. Now you’re making me go back and re-read The Family Upstairs, so thank you.

Paul Tumey: One of more poignant moments in the story you tell is when you point out that, if Herriman was legally classified as an African American, he would not have been allowed to own the homes he bought. Am I getting that right?

Michael Tisserand: Absolutely. I've seen the racial covenant that was attached even to his beloved home in the Hollywood Hills. It’s sobering to read.

But I don’t want to leave The Family Upstairs yet. What other comic strips had central characters who remained offstage? Miss Othmar and the Little Red Haired Girl come to mind.

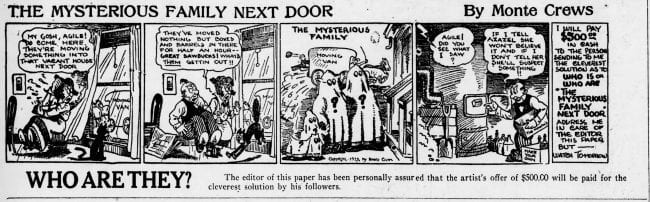

Paul Tumey: There's Monte Crews' totally unknown 1922 screwball daily comic strip called The Mysterious Family Next Door, which I have often thought was probably inspired by Herriman’s strip. Some of the characters wear outfits that vaguely look like KKK sheets -- even the dog! My favorite example of a hidden character is the series Rube Goldberg did for Collier's Magazine from 1929-1931 called The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgazola Butts, A.K. The star of that comic series is never once shown!

Michael Tisserand: In The Family Upstairs, the invention of the upstairs neighbor brings the strip to life for me. I laugh the hardest at the Dingbats when they're battling the family. Otherwise, the strip is pretty similar to Herriman's other domestic strips, such as Mary's Home From College. Which I love also, but not like when they’re battling the neighbors.

I also love how the storylines sort of ping pong back and forth between the Dingbats' adventures and the Krazy Kat comics then running below that strip.

Paul Tumey: A bit like breaking the color line…

Michael Tisserand: Right. Or the horizon line. Or any line. And in those early Krazy Kat comics, Herriman sometimes dealt quite explicitly with racial themes, even when it was more obscured in his "human" strip.

Paul Tumey: In your reading of Krazy Kat, did you see many examples of Herriman's "hidden" commentaries on -- what could one call it? -- society's racial intolerance? This might be a good place to ask if you might talk for a moment about the connection you make in the book between the great heavyweight champion boxer Jack Johnson and the evolution of Krazy Kat.

Michael Tisserand: Herriman's father and grandfather were very politically involved in New Orleans, and it seems as if Herriman's father was at least somewhat involved in his union in Los Angeles. But Herriman actually seems disengaged politically. I don't even see evidence of him registering to vote, as opposed to other members of his family. And in his political cartoons, while they’re wondrously drawn and filled with great little jokes, he rarely seems to sustain outrage the way that someone like Thomas Nast or Frederick Opper does. With one great exception: Herriman's cartoons about the boxing color line.

Paul Tumey: Could it be the issue of black boxers not being allowed to fight white men was such a heated controversy at the time that it served as a sort of lightning rod for public debate, especially in newspaper sports cartoons? Perhaps it emboldened Herriman to be more forthright. Or perhaps it was even expected by his editors?

Michael Tisserand: There was such raw hatred in the press toward the notion of white boxers being challenged, and of course defeated, by blacks. Jack London's journalism is staggeringly ugly. But the Hearst men saw it differently. Tad Dorgan was a lifelong supporter and friend of Johnson's. Plus, they loved boxing, and they recognized that the white boxers they said formed the "Lily White Club" were hurting the sport by denying fans of the best matches. The Hearst men ruthlessly mocked these boxers.

Paul Tumey: In addition to Dorgan, Rube Goldberg came out in support of Johnson against Jeffries, and seemed to greatly admire him, even though some of his sports cartoons are jaw-droppingly racist. But how did Krazy Kat emerge from this whipped-up maelstrom of conflict and social change?

Michael Tisserand: Herriman's sports cartoons were different than the rest. Unlike Dorgan, he rarely used his cartoons to explicate or even demonstrate much knowledge of the sport. Instead, he went for gags and grand, classical themes. He used metaphor after metaphor to illustrate the boxing color line, then finally settled on cats, starting with cartoons about the black Canadian boxer Sam Langford.

When the much-hyped "Fight of the Century" was finally getting underway in Reno on July 4, 1910, the other cartoonists were sent to Reno, and Herriman was summoned to New York to sort of report on the home front. He began drawing incredible cartoons that specifically examined the hypocrisy of white boxing fans. In one, a child that is taught that the imaginary line around the world is no longer the equator, but the race line. And in my favorite, a man sells "transformation glasses" to turn the whites to black and the blacks to white. Or, as Krazy Kat and Ignatz would later call it in that great comic in which they trade colors to try to fool a beret-topped egghead art critic, it was another study in black and white.

Paul Tumey: Wow -- that is a great example of how restoring cultural and historical context adds so much depth and power to a comic.

Michael Tisserand: The fight in Reno was on July 4. Twenty-two days later, on July 26, Ignatz first beaned Krazy, who was now beginning to resemble Herriman's caricatures of black boxers. As is often the case with Herriman, I don't see this as a direct commentary, but as another example where he's throwing in all this material and letting us sort it out. It’s like Herriman's finding a side door into this conversation, and inviting us in.

Paul Tumey: A side door, yes. That seems to be Herriman’s way. He was private man with a very public job.

Michael Tisserand: When I reeled through page after page of Los Angeles Examiners and New York Evening Journals, I realized how much is lost when we read these comics in anthologies. God bless the anthologies, of course, but reading the comics as they respond to the news stories and sports stories, and to each other, returns them to history yet also frees them, bringing jokes to life that had been sort of dormant.

There was, for example, a series of stories in the New York newspapers in September 1910 about wealthy people acting loony, followed by cartoons that turned on the word "loony," including a Krazy Kat in which a white cat utters "Loony Kat" after a courtship scene.

Paul Tumey: There’s a kind of “code” aspect to Krazy Kat that I think your book helps restore. As I read the first half, I kept thinking about the Uncle Remus Br’er Rabbit stories that tell stories of oppressed black slaves in disguise, as funny animal stories.

Michael Tisserand: There are Creole French versions of those Uncle Remus tales that were collected on the Laura Plantation, outside of New Orleans, right before Herriman's birth, and it's certainly fun to speculate that Herriman heard some of these as a child. Plus, Herriman's first weekday strip was the four-panel Maybe You Don't Believe It, from 1901, in which he reworked Aesop's fables and gave them happy endings. It only lasted for five episodes but it provides an early glimpse of the world that would become Coconino County. And he was all of 21 years old.

Paul Tumey: So maybe one way to understand Krazy Kat and some of Herriman’s other work with animal strips is to see it as a sort of comic reversal on popular folklore of his day.

Michael Tisserand: There’s an amazing conversation relayed by Robert Naylor, who helped Herriman with Embarrassing Moments. Naylor said he once asked Herriman why he "reversed natural phenomena" -- put on the transformation glasses, perhaps -- with a mouse attacking a cat while being thwarted by a dog. Naylor reported that Herriman said that life is so absurd, he simply draws what he sees. As Naylor tells it, Herriman considered the whole thing -- and here I think he meant life itself, and this maybe gets pretty close to describing Herriman’s philosophical and spiritual conclusions -- sort of a wry joke. It’s as if somewhere from his boxing cartoons to the later iterations of Krazy Kat, Herriman found a way to laugh at it all.

Paul Tumey: And to use the alchemy of comics to transform some of life's pain into entertainment, and, I think, art.

Michael Tisserand: Yes! Stanley Crouch wrote about this eloquently in his essay “The Blues for Krazy Kat” in the Masters of American Comics catalogue. Herriman was talking about race and identity -- as profoundly as anyone has, in my opinion -- but I never see that as his big "Topic." It was just part of his world, and the world he created, even if others were slow to recognize it.

Paul Tumey: There is so much in Krazy Kat -- a work that, as far as I can tell, Herriman added to every single day of his life for over thirty years. It's Shakespeare, Dickens and Schulzian in that it's a vast universe to explore...

Michael Tisserand: And Cervantes, whom Herriman read as a schoolboy. And other writers who I didn't know about at all until I Googled some odd phrase from Krazy Kat. Over the past ten years, I learned to accept that Herriman would always stay ahead of my research. In fact, one night I actually dreamed that I was talking to Herriman, and I told him that I had discovered his birthday, and he just laughed at me.

Paul Tumey: Yes, Cervantes! Obsessive personalities are a running theme in screwball comics of the time. It was a basic formula -- a character like Ed Carey's Professor Hypnotizer was obsessed with charming people, and of course, it always backfired. Herriman's Major Ozone was very typical of the period, for example.

Michael Tisserand: Major Ozone also reflected news accounts of health nuts that were running around New York during this time. But there is also this lovely self-delusion in Ozone that seems to be carrying an influence from Cervantes.

Tad Dorgan said that Dickens was Herriman's favorite writer, but Don Quixote seems to me to be galloping across his work as much as anyone else -- certainly with Major Ozone, but also with Baron Bean, and all the holy obsessions that fuel Krazy Kat.

End part one. The "konversation" will continue in Part Two.

A short video Michael Tisserand made about his book, featuring previously unseen home movie footage of George Herriman: