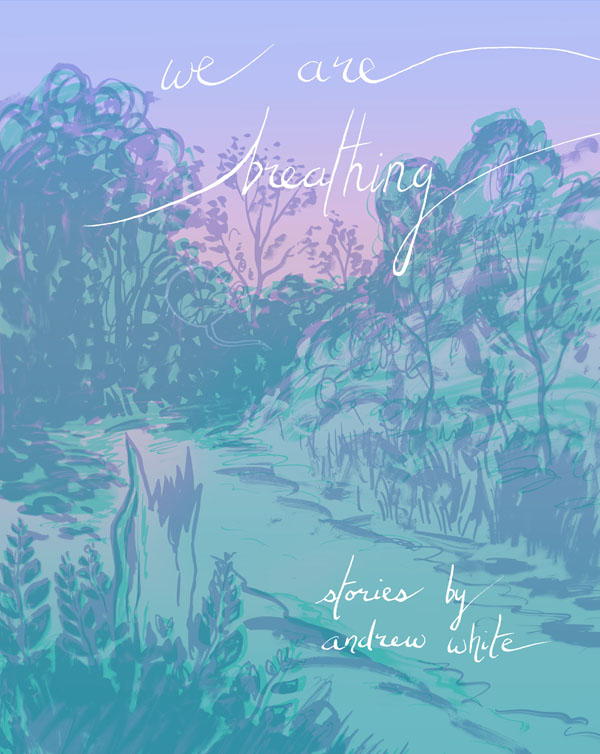

Andrew White emailed me about a year ago. He asked that I interview him. The following is the result, after much delay on my part. The interview will be included in Andrew’s new book, We Are Breathing.

Andrew White emailed me about a year ago. He asked that I interview him. The following is the result, after much delay on my part. The interview will be included in Andrew’s new book, We Are Breathing.

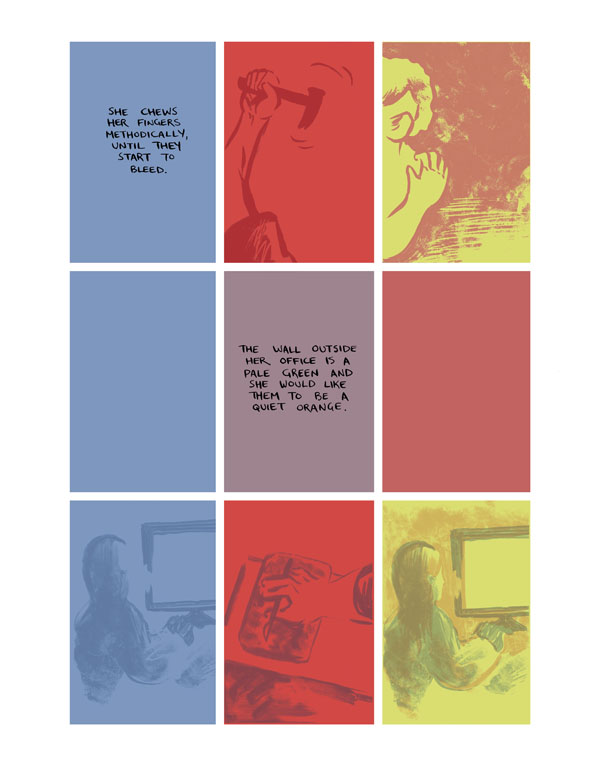

The book collects his older stories and strips, newly represented for an audience that may have missed them the first time. It’s for anyone who may have caught bits and pieces of his work over the years, but never saw the larger picture. Andrew’s comics utilize abstraction, and they can focus on quiet things. But past the first glance, most all of them revolve around a story. He has made comics that are more so poems or meditations or reflections, but his overall focus and progression is toward narrative. Andrew’s comics (particularly those featured in We Are Beathing) show the reader a story from a hidden or unconsidered perspective. Maybe even one that’s inanimate or spectral.

That element fosters abstract imagery and sometimes loose thematic connections, but it presents possibilities for stories. It asks the reader questions, like: What’s sitting right in front of you, or out your window, or inside a memory? What’s going on there with it? How can it be shown or viewed? What do you recognize, or want to say, or struggle with that’s inherent to it?

While Andrew’s work can challenge a reader, it can connect them to their experience of the world. It can drop them inside a particular vantage point and invite concentration. Maybe this is a vague, generalized way to describe his comics, but apart from their specific “abouts,” I see this as the value in his work. His comics create a space to contemplate and thoughtfully look at this place. Or look at other works of fiction. Or the artists who created them. And it’s all through the lens of comics. Andrew utilizes certain aspects that are inherent to the form, and he places them at the forefront. He really builds his stories around them. In We Are Breathing, the backbone is the page layout and his sparse, yet vibrant images, where color is a character in the story. The fact this is his early work says a lot.

* * *

Alec Berry: I don’t know you very well, but I’ve usually viewed you as the type of creative person who likes to leave projects in drawers. Or you’ll likely complete something and quickly move on, with little sight in the rearview. What was it like compiling this collection of earlier work? What’s the motive to assemble this, and why do so right now? Maybe I’m incorrect in my assumption.

Andrew White: No, I think you’re right. As we’re talking, I have a handful of complete or near-complete projects with no immediate plans to publish them, and once a comic is printed, I don’t spend much time thinking about it, or looking at it, or promoting it.

But that does mean the work can be more easily forgotten, both by myself and by readers. So, with that in mind, I’m collecting old work because I want people to see it and because I want to see it again myself. I wanted to reflect on these comics, the fact that I made them, and how they do or don’t hold up to my critical and aesthetic standards now. I wanted to see how the ideas in them fit together. I like the idea of holding a book in my hand that contains years of my life.

Reading it, I was reminded of the fact that you have been making comics for quite a while. I became aware of you in maybe 2011 or 2012. It was when some of the work collected here started to appear. And I believe you were creating comics before that, too. That’s more than a decade as a maker in this art form.

People come and go in comics, and people stay and stick with comics. I’m interested in your commitment to this thing. More so than regularly making new work, it seems like a practice for you. Maybe it’s meditative, which some of the work collected here seems to reflect.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. I suppose that’s another motivation for putting together a collection. As you know, one of my main projects has become an annual comic called Yearly, which I’ve committed at least notionally to publishing once a year until I die. So, I’ve made the idea of sticking to comics a core part of my creative practice. In some ways that were a natural choice, but in other ways, it’s something I actively pursued because as you say I’m well aware that people often come and go in this world. I understand why that happens; for instance, sometimes a person’s life situation just doesn’t allow them to devote the many, often unpaid hours to comics that it requires, but I’ve always admired the folks who found a way to stick with it despite the general lack of any tangible rewards. I hope to be like that myself.

Sticking with comics is also more under my control than whether I make good work. Or at least it can seem that way. In other words, I might not know whether I’m making comics that connect with people, or whether I’m improving from one project to the next. But I can decide today or tomorrow, or in ten years to keep drawing pages. There’s comfort in that.

Beyond that, it’s very simple. I love making comics. It’s the only art form that has ever interested me as a creator. I like drawing. I like telling stories. One of my greatest pleasures is working through, and hopefully solving, some challenge or weakness in a comic. You said something along these lines to me recently, so maybe I’m borrowing your words. I like the mental exercise of that problem solving, the ability to retreat into myself with ideas that stimulate me. I wouldn’t get to enjoy that if I stopped making new work.

I’m also aware that my continued enthusiasm for comics is in part a function of my privilege and background. I’ve never been forced to take an art-related day job that might sap my energy or enthusiasm for drawing on my own time. I’m a straight white dude at no risk of quitting comics because I’m harassed or otherwise made to feel unwanted.

Your comics could be considered abstract in their appearance and function, but ultimately, they seem committed to the narrative. They find moments or fractures in the story to anchor to and report from, and sometimes the point of view feels fleeting or ethereal, maybe even of a spirit. Your drawings and panels reflect this. They are clear in what they are (sometimes), yet they can feel more like atmosphere than literal depiction, at times. This approach isn’t for everyone, but you’re committed to it, and you’ve built your work around it.

I was thinking about it last night. I feel like books, drawings, songs, etc. attract their audiences because they’re ultimately giving something to those that experience them, whether information, a sense of connection, intellectual stimulation, something pretty, something loud. What I described above is why I like your comics. It’s a chance to look at storytelling another way. Is there a similar feeling for you when making them? Or do stories just present themselves to you in this way?

It’s only one piece of your question, but I’m happy that you noticed the balance between abstraction and narrative because I’ve been chasing that for a long time. I love stories, but I also love drawings that just function as mark-making. Those two worlds don’t always intersect, but with comics, I think they fit together naturally. Think, for example, of the way that some panels in even the most traditional narrative comic might look completely abstract when considered individually. A ball zooming across a field in a sports manga. An explosion of dust and stars in a newspaper strip. A chiaroscuro figure barely visible in a sea of black ink. Images like that fascinate and compel me, so I want to make work that pushes even farther in that direction, creating abstract sequences that have narrative resonance because of the context in which they appear.

I do feel like some of the pieces in this collection of early work use abstraction or tone as a crutch. I create an atmosphere where readers assume a lack of clarity in the story or in what a drawing depicts is purposeful — when in fact I wanted that story or that image to be perfectly clear, but my skills just weren’t up to the task! So, I’m working to improve on that front and ensure the moments of mystery are intentional.

In terms of whether this approach to storytelling comes naturally to me, I sometimes think about the poet Paul Valery, who supposedly said that he couldn’t write fiction because he couldn’t bear to write sentences like, “The marquise went out at five o’clock.” Like most good quotes, this can be interpreted a number of ways, but to me, it means that constructing straightforward narrative works can often feel like a chore to me and so it probably won’t be compelling to my readers. Plus, Valery’s objection is even more true if you have to draw the marquise going out in addition to writing it!

I have sometimes tried to create more narrative work, but it tends to either collapse under the weight of accumulated plot points or become more ephemeral and poetic over time as I refine it. So I might imagine a story where the marquise does have to go out at five, but then I wonder — could that perhaps be implied instead of depicted? Could a sequence where the marquise goes out be more concerned with the rhythm of his life or with the feeling of stepping out into a sharply cold evening than with the simple communication of factual information? My interests are often pulled in that direction. But I also want to be kind to my readers by providing some amount of narrative, some straightforward statements of fact to allow folks a path into the work.

Describing my preferred point of view in storytelling as ethereal is another good insight. A number of my comics, both in this collection and in more recent work, have even featured ghosts or ghostly figures. I suppose ghosts are a good window into some of the themes that interest me — time, death, memory — and I also love the idea of a ghost, a presence, that hovers just behind your shoulder in quiet observation. Placing the reader in that position creates a sense of intimacy that I often want to cultivate in my work. Second-person narration, which also appears in a few of these comics, can help create that same feeling.

Do you consider the reader much? I feel like you do, but some of the comics in this collection, mostly the one-off meditations or short poetry pieces, feel more concerned with whatever you were experiencing in the time you made them. They seem more for you, and they’re a bit spontaneous (seemingly). I’m curious how you approached that type of work at the time you made it, as well as how you view it now.

I’m certainly thinking about the reader in terms of clarity, going back to what I mentioned previously about wanting to be more intentional regarding what parts of my stories are clear versus left mysterious. I suppose truly self-indulgent work wouldn’t be concerned with that. Plus, of course, I do publish the work. So, I want people to read it.

But some cartoonists talk about imagining an ideal reader, or even writing for a specific person, and I don’t often have that in mind. I think all the work is for me at the end of the day. While I feel true, immeasurable gratitude for anyone who reads my comics, let alone anyone who lets me know that they’ve enjoyed my work, I often derive the most satisfaction from my own sense of whether or not a piece has succeeded.

In terms of the short poetry pieces, especially the ones that appear in this collection, it’s true that they’re often more spontaneous and less considered. For example, the one-page strips I’ve chosen to include here are culled from a much larger selection of work that I posted online from about 2012 to 2015. Hundreds of strips. The best of them are good, the worst of them are clumsy, and a significant portion is mediocre and repetitive. I improved from churning out that work, of course, and sometimes I did stumble upon making a good strip, but it also encouraged (or maybe formed) a habit of, at times, working too quickly and without enough consideration.

So, I’m at a stage now where I want to tackle that kind of short, poetic work more carefully and push it to the next level of quality. Hopefully, I can manage to do that without losing the poetry or spontaneity of a strip that is drawn quickly.

With some of the earlier work in here, you were just coming out of Frank Santoro’s cartoonist correspondence course, and maybe you were applying some of the lessons learned in it to your practice. I know you made comics before his class but was that a major shift for you? If so, how? And does that experience still have any direct influence in the way you make things?

I took the second iteration of Frank’s correspondence course in spring 2012 and drew all but the first comic in this collection after that time. I remember Connor Willumsen was in the same running of the course, and maybe Tyler Landry, too? Then, from 2012 to about 2015, I made one-page comics for Comics Workbook and was involved in other aspects of that project, such as co-editing the 10 print issues of Comics Workbook Magazine with Zach Mason. Frank was incredibly encouraging to me during that period, when I was very unsure of myself and the value of my work. That was very kind, and I’ll always appreciate it. We’re still good friends now, and he continues to be very generous with his time and advice.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention the comics friends I made through my association with Comics Workbook and who also influenced my work — people like Sal Ingram, Madeleine Jubilee Saito, and Samuel Ombiri. Juan Fernandez is another friend I met at that period who has now channeled some of the ideas from Frank’s course into his own teaching practice. I’m excited to see where that goes.

I think, at the highest level, what I took from the course at the time is an awareness that every element of my process should be carefully interrogated and can be changed. That’s true even for parts of the process that seem self-evident like the idea that comics should be penciled, inked, and then colored. That perspective, and my resulting willingness to adjust how I make comics, is still important to me now.

However, it does seem to me that some folks have made a parlor game out of guessing which cartoonists have taken Frank’s course and/or assume that any cartoonists who have taken the course continue to approach comics with Frank’s method as their primary influence. I’ll admit that does bother me a bit; it seems like a lazy critical perspective. Maybe people do this because Frank’s viewpoint is so publicly articulated and so specific in some of its precepts (Grids! Work in layers of color! Draw at 100%!) that it can be tempting to assume any comics with some of those visual elements are following Frank’s example. I’m sure the course was an influence on most or all of the people who took it, but I’m also sure that each of those cartoonists has a varied and complex set of influences as well as their own unique perspective.

Yeah, definitely. That makes sense. I feel like comparisons are a good shorthand for a quick description or pitch, but they don’t explain nuance or why very well. The comparison point can overshadow what’s actually on display, too. Do you feel your participation in Frank’s course has informed how people have decided to see your work? Has it limited the perception of it?

I hope not! That’s not for me to say, I guess.

Of course, I don’t have a problem with citing stylistic comparisons or possible influences as one lens for talking about a comic. I would certainly be happy to have my work compared to Frank’s because he’s a great cartoonist. He would be an influence even if I’d never taken his course.

Reading “While A Soft Fog Wanders”, the story echoes what you said above, about individual panels appearing abstract when removed from their context. But you make that the point of the story, in a way.

Individual scenes transpire per panel as the action referred to in the title (a soft fog wandering) occurs, and some of those scenes continue in subsequent panels, but the story mostly revolves around isolated shots. You, or an omniscient narrator, show us individual, seemingly unrelated images, yet that same narrator conjures an interaction between these images, to create something larger.

I’m interested in how you view perspective in comics, as a tool, and as an underlying force. I don’t mean to be mystical about it, but that story, specifically, gets at something beyond a person’s ordinary ability to see. And comics tow a weird line in terms of story POV. Do you think comics can show us something about, not necessarily individual perspectives, but perspective itself?

There’s definitely a mysticism to the process of comics like Soft Fog, just because it can feel a little magical when a comic like that works right. I generate images that feel compelling or linked to me for whatever reason and then place them in a sequence that seems correct. It’s difficult to talk about because the process of deciding how to sequence those images is very intuitive, but I also think about it very carefully — reordering panels many times, removing, or redrawing images, etc.

When I made Soft Fog, I’m not sure I could have told you what it was “about.” I certainly couldn’t say now, but that comic and others like it feel successful when they evoke a consistent mood. A fuzzy feeling at the back of your neck or in the corner of your mind.

On perspective, I’ve always enjoyed the way that comics can jump from scene to scene, image to image, in a way that, at least for me, can feel more natural than say a montage in film. Many people have talked about how this reflects the way our memories work, with sequences of non-linear associations, but I’d go farther and say this is often how my brain works in general. Jumping from one thought to the next, making connections that are hard to retrace once a few seconds have passed. I enjoy trying to replicate that in comics.

What do you want from a comic when you read it? What can a great comic do?

At this point, I’m always reading comics as a cartoonist on some level — looking for tricks I can steal, noticing tiny details in the printing quality, thinking about how I might change the comic if it was my own work. This can be frustrating because it risks taking me out of the reading experience. But it also means I’m just as likely to have my breath taken away by a scribbled shadow as by some masterful moment in the storytelling. That range just doesn’t exist for me in any other medium. In prose, which I also love, I might come across a beautiful sentence, but for me, that’s not the same microscopic encapsulation of the creator’s worldview as a quickly dashed off but perfect drawing in the corner of some panel. So, I suppose that’s what I’m looking for in a comic: an experience where the many, nested levels of art and writing and design and craft that go into the work are perfectly interacting, speaking to each other and creating something unique.

Another way of describing this is to say that when I read work by a great cartoonist, I sometimes have the strange and wonderful experience of going out into the world and being able to picture what I’m seeing as if that cartoonist had drawn it. It never lasts long. But it’s always really lovely.

When adapting another’s work, do you simply apply how you see the world to it? Or are you trying to find out more about that particular author’s lens? In this collection, you adapt a short story by Italo Calvino titled “A Beautiful March Day”. I want to say it’s one of the very few times you’ve depicted violence at all, let alone so directly. Violence is inherent to the story, but you decided how to present it and executed that. It’s an interesting place for you and Calvino to meet.

It’s interesting to reflect on that story, which I included because it’s the earliest piece of my work that I can look at today without completely cringing. With that in mind, I’m sure it isn’t a coincidence that I see in that comic the seeds of several threads that are still important to my work today.

I still enjoy adaptation — or perhaps appropriation, in some cases — and the process of condensing, cutting up, and even resequencing text written by someone else is an exciting challenge. I suppose I am trying to understand the author better and use their lens as a way of pushing my work to new places. But I’m also trying to accentuate certain elements of their work; a sense of mood or place, for example, that might be present in the original piece but better emphasized using comics.

I should also mention Calvino has remained an important influence for, among other reasons, his ability to write short stories that succeed individually but work together to create a broader narrative. Plus, it’s funny to me that this is an adaptation three or four levels deep — from an actual historical event, to historical accounts of that event, to Shakespeare, to Calvino, to me. I included a few snippets of dialogue from Shakespeare as a nod to that fact, I hope more to poke fun at myself than to be pretentious.

Your point about violence is perceptive — you’re right, of course, but that hadn’t occurred to me. My first thought is that this might be related to my disinterest in traditional approaches to storytelling, which we’ve already discussed. Violence is so often inherent to our conception of what “conflict” means, in a narrative context, and maybe I’ve tended to avoid it as a result.

Yeah. Or, violence is an idea that’s uninteresting to you. Which is totally fine. That said, I could see your comics distilling and depicting violence or violent events effectively. I think you could present violence in a way that impresses upon a reader in a different way, that maybe dissects it or observes it from another vantage point. Excuse me for trying to pawn ideas on you. I guess I just want to see your version of a fistfight, haha.

Are there other ideas, themes, threads, or approaches that are featured in this collection that you believe you’re still exploring? Adaptation is one example. But what else? Of those ideas, what has telling stories about them taught you of these concepts? Or, has your work only presented you with more questions?

I’m still interested in second-person narration and in finding other tools that create a sense of intimacy and connection between myself and the reader. I’m still trying to make work that has some completely abstract and other fully narrative sequences, and that thrives in the space between those worlds. I still spend a lot of time thinking about time and memory. I will always love to draw trees and water and wispy clouds.

On the other hand, I do think I’ve left behind the approach of Soft Fog or some of the Comics Workbook strips, where very loosely related images hint at some tone or theme. That approach may appear in portions of my comics going forward, but it’s not enough to carry a project by itself.

I also think I’m less attached to formalism and constraints than I once was. I’m more aware of the complexities and the nested levels of problem-solving that must be brought to bear to make a good comic. As a result, I’m often more impressed — in my own work and in the work I read — with subtlety than with some “clever,” formal trick. Though I do have a soft spot for that stuff. I identify quite a bit with a Dash Shaw interview from many years ago, where he describes himself as “annoyingly a formalist.” I feel the same way, in that I can’t help but be drawn to some degree of formalism.

I think one evolution that starts to appear in the last few comics in this collection, and that I’m still grappling with today, is my desire to come to some conclusion, however small, about these ideas that I’m working through, again and again.

In other words, I’ve come to feel that an important goal with many of my comics is to have a happy ending: not trite, superficial happiness, but a happiness that comes from grappling with difficult ideas and arriving at some truth, some insight.

Perhaps “satisfying” (or an ending that does not lean on the narrative tropes around satisfaction or resolution) is a better way of describing it.